Although not to the degree touted by the BN as a ‘referendum,’ the Cameron Highlands by-election does indeed offer important lessons.

So far, in valuable analyses, the focus has been on ‘ethnic voting’ patterns (in which the Malay community showed the most swing away from the new federal government), the choice of candidates and the need to shift campaigning practices in rural/semi-rural areas.

While these issues were important in shaping the final vote, they miss the larger point: Pakatan Harapan’s biggest mistake in Cameron Highlands is that it adopted the practices and assumptions of BN in the election. In Cameron Highlands, Harapan locked itself into a ‘campaign as usual’ mode that did not effectively embrace the reform momentum that put it into office or move its campaigns out of the ‘old Malaysia’ mode.

Analysis of results

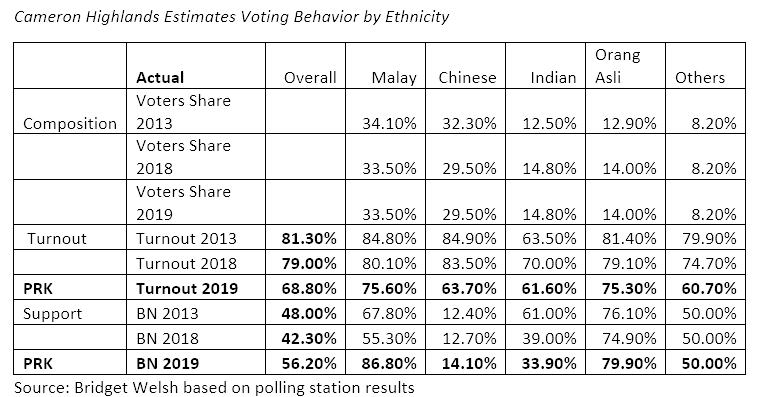

A number of studies have examined the results. Below, using a statistical method of ecological inference, is my analysis of estimates of voting behaviour in Cameron Highlands. There are three important findings.

First, turnout dropped across the different ethnic communities, especially among Chinese and Indian voters. This is not a surprise given the timing of the by-election before Chinese New Year but speaks to fatigue and disinterest among voters across communities and within Harapan’s political base.

Second, the swing in support along ethnic lines is biggest among the Malays – a large swing of over 31.5% to BN. This was followed by an estimated swing in Indian support for Harapan, by 5.1%, and estimated swing in favour of BN by Orang Asli voters of 5%. The BN’s victory was indeed tied to the candidate and race-based mobilisation.

Finally, Harapan witnessed an erosion in its political base, losing support in terms of both turnout and even among Chinese voters, although not to the extent as losses in other communities. Harapan’s Cameron Highlands defeat should be seen as their own weaknesses in the campaign.

Persistent racial mindset

I argue that a crucial part of the erosion of support comes from Harapan’s adoption of ‘old Malaysia’ practices. Perhaps the most rigid of these practices is the continued insistence of seeing Malaysians race first. No one denies the importance of ethnic identity in Malaysia, which is tied to rich cultural practices and been embedded in social and political life for decades. Yet, at the same time, the myopic and shallow focus on race constrains much-needed reform in political engagement.

BN survived 60-plus years on using ethnic politics to legitimise and maintain its hold on power. They are continuing to rely on this old model for political survival today.

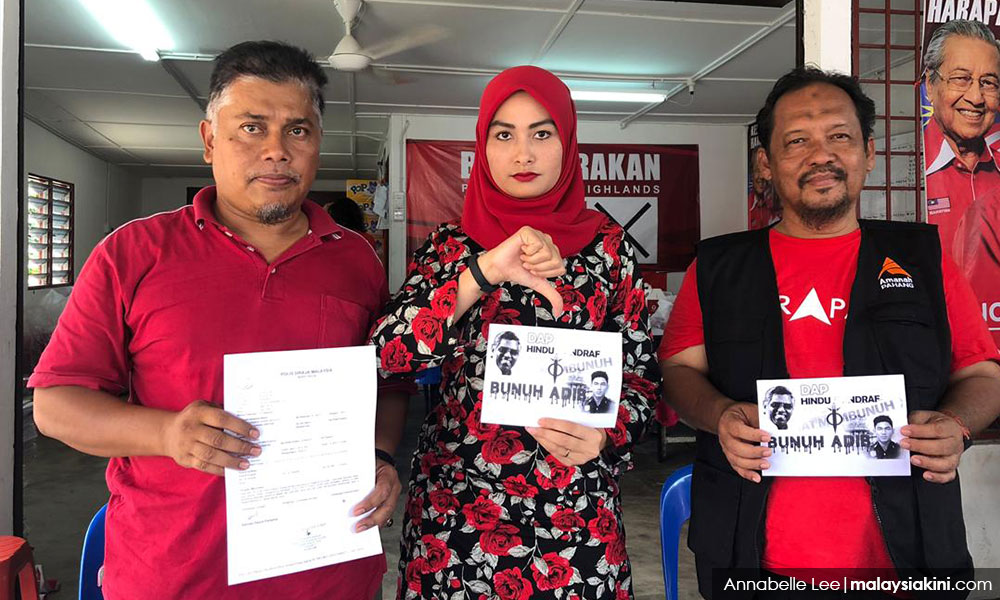

In Cameron Highlands, their victory was tied to two racialised factors: the strategic upfront choice of a candidate for his race - Ramli Mohd Noor representing Orang Asli - and the insidious behind-the-scenes anti-Indian/pro-Malay racism that was emotionally used as a tool to bring back the support of the Malay community and secure a BN victory. The BN fed on sentiments of ethnic displacement and insecurity, especially among the Malay community, as they have done for years.

The mode has changed somewhat, however. Victimisation has taken on even greater traction for those displaced by Harapan’s control of government. There is a deepening of insecurity.

Also, the current political environment has fostered alliances among opposition parties, with Umno taking a backseat behind the BN label. PAS and Umno’s adoption of a ‘Pan-Malay’ sentiment is not new (as it featured in GE14), but it has gained ground. At its core, the alliance is a political strategy for the return to power of elites who have been displaced rather than genuine representation of the Malay community at large.

It builds primarily on the same negative sentiments that got Umno kicked out of office - anger and resentment, and, as such, does little to actually empower the Malay community, or any other for that matter. The BN, however, cannot be faulted for relying on what has done for decades. It won them a seat in parliament.

BN’s dominant narrative

Harapan, on the other hand, allowed the BN to dominate the campaign using race. Not only did Harapan not project a viable alternative narrative, it adopted racial politics full on.

By concentrating on the Orang Asli, a community who has seen decades of exploitation and neglect (even effectively ignored by Pakatan when it was in opposition), Harapan reinforced the focus on specific communities rather than voters at large.

This fed into the sense that Harapan is representing minorities rather than majorities, playing into the sentiments being stirred on the ground. The voting analysis shows it did not even yield them results, as their share of the Orang Asli voted decreased.

Perhaps the worst example of Harapan’s old Malaysia campaigning style was the BN-like promise of minority ethnic representation in cabinet, sounding so similar to BN songs sung in the Teluk Intan by-election and elsewhere. It is no wonder that BN won, the campaign was their race-based song.

Najib, Najib, Najib

Harapan opted to play the Najib card in his home state. Harapan continues to believe that it can get mileage out of attacking the former prime minister, the same man they have imposed multiple charges for alleged serious crimes. This strategy failed, and has been decreasing in saliency since GE14. The more Harapan focused on Najib, the more the sympathy sentiment was stirred among some of his traditional support base.

Despite the evidence, many in Umno’s political base continue to believe in Najib and do not see wrongdoing, in part because it would mean they were also responsible for facilitating the wrongdoing themselves. For others, especially in Umno’s political base, the focus on Najib further reminded them of their political displacement.

It is important to remember that the 1MDB scandal had less impact in rural and semi-rural areas in GE14 as well. This refrain also had less impact on Harapan’s political base. More urban voters understand that Najib faces a court process, and they were angry, but this sentiment is no longer as strong as it once was given the fact that Najib is no longer in office.

The focus on the past, however, was a common BN practice, another one that Harapan has adopted in its hustings. Rather than focus on what it is doing in government, they continued their opposition mode of attacks on a man no longer in government. Ironically, this has served to empower Najib as his name was headlining the campaign rather than those in Harapan, or Harapan’s candidate in Cameron Highlands for that matter.

Harapan seems not to fully appreciate that it needs to focus on what it is doing now and will do in the future if it is to maintain support, and show how it is working to deliver for the rakyat. They need to embrace their role as government, not the opposition. Instead, they played an old record that did not jive.

Clean election

Of all the old practices that Harapan seems to be adopting, the most ironic of those in Cameron Highlands was the violations of good electoral practices.

The by-election was called because of vote buying in the first place. Less than one day into the campaign, these issues were raised on the part of Harapan, along with questions about the use of government resources and ‘promises’ from government. The campaign finished with the Harapan candidate infringing election procedures by wearing the coalition logo in a polling station.

The irony is striking. One of the main reasons voters in Harapan’s political base voted for the coalition was electoral reform. This election could have served as an opportunity to embrace a fairer and cleaner electoral process. Despite denials and explanations, Harapan came off as not differentiating themselves adequately from BN in its ‘irregular’ campaign practices. In fact, they seem to be replicating them.

The trend appears to be for the Harapan to use patronage and promises as a means to garner support. Harapan has yet to realise that given the differences in the coalition and the reality of less resources at hand, they are unable to replicate Umno on the ground, or PAS for that matter.

None of Harapan’s parties has the machinery or membership base, especially in rural and semi-rural areas. They will likely never have the same control over the state bureaucracy, and most certainly are not yet in a position where many of the promises they did make were seen as credible.

Patronage

The broader trend is that patronage politics is weakening in Malaysia as a form of political engagement with the electorate. Patronage is concentrated among political elites, and while this practice at the top remains strong, in connections to ordinary voters, it is eroding. It has been so for some time.

Harapan faces an uphill and arguably a losing battle engaging in local patronage without the machinery on the ground and necessary social trust and connections that complement this practice.

It is not just about the logistics, the question is whether reinventing the patronage wheel is the right path ahead. Are Harapan parties able to become institutionalised similar to Umno or PAS? Should they do this? Adopting patronage is based on assuming voters are about what they can get out of the system as opposed to the ideals and values a party represents or the policies it implements and delivers.

Harapan’s strength was about promising change, about revamping the system and introducing new policies and values. It was supposed to be about cleaning up the system. A focus on replicating local patronage patterns and in the process, opening up grey areas in electoral practices is in contrast to what put Harapan in office.

Studies show that political parties often mirror each other both in government and in opposition. It is a real challenge to get out of copying what others are doing and setting a different course. It is possible, however.

Given Harapan’s learning in opposition and adaptation, the record of change in tactics and practices is there. Cameron Highlands shows, however, that if Harapan follows BN and Umno, it will lose.

BRIDGET WELSH is an associate professor of political science at John Cabot University in Rome. She also continues to be a senior associate research fellow at the National Taiwan University's Center for East Asia Democratic Studies and The Habibie Center, as well as a university fellow of Charles Darwin University. Her latest book is the post-election edition of ‘The end of Umno? Essays on Malaysia's former dominant party’. She can be reached at bridgetwelsh1@gmail.com. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.