MP SPEAKS | I call upon the Pakatan Harapan leadership to take responsibility for the khat issue.

Unlike Donald Trump who was directly elected president of the United States by the voters, the prime minister of Malaysia was appointed pursuant to an agreement of the Harapan leadership. The leadership ensured Harapan members of Parliament forming the majority of the Dewan Rakyat supported Dr Mahathir Mohamad as prime minister.

Thus, unlike the US president, the buck does not stop at the prime minister’s office. The Harapan leadership and the majority of the MPs are ultimately and collectively accountable for the decisions and policies of the prime minister and his cabinet.

The Harapan leadership, therefore, cannot wash their hands of the growing and escalating tension arising from the khat issue and abdicate responsibility. Harapan leadership must take urgent and immediate action to resolve it.

If the Harapan leadership is serious about salvaging what remains of its tattered credibility, the leadership must resolve this issue in accordance with the rule of law, the constitutionally guaranteed fundamental freedoms and the promises made to the voters. This means upholding Pillar 5 of the Harapan manifesto and not use the excuse that Harapan did not expect to win. The promise is at page 102:

“The Pakatan Harapan government will implement policies and programmes that unite the nation, create an inclusive society and maintain the harmony of multi-racial and multi-religious Malaysia.”

The promise extended to Harapan’s confidence that its policies and programmes will become a global model of inter-racial and inter-religious harmony.

Unfortunately, the promises have not materialised.

On the contrary, the banning of the Dong Jiao Zong meeting and handling of the khat issue reveal this Harapan government not only flouted basic principles of the rule of law but also practices the same or an even more severe form of oppression, ethno-nationalism and politics of exclusion than the previous regime.

Rule of law turned upside down

The police’s decision in obtaining a court order to ban the Dong Jiao Zong meeting on the ground that certain groups have threatened to commit riots is perverse and a travesty of justice.

The duty of the police is to uphold laws by protecting law-abiding citizens and taking action against those who break the law. By banning the Dong Jiao Zong meeting, the police and the Harapan government have turned the meaning of the rule of law on its head.

Those who acted illegally in committing the offence of issuing threats of rioting are appeased and allowed to roam free. Those who acted legally to peacefully hold a meeting to exercise their constitutional rights of freedom of assembly and freedom of speech are denied and liable to be imprisoned if they proceed.

The ban when compared with the manner the police dealt with the incendiary and seditious speeches in the Malay Dignity Congress shows the police have acted with an uneven hand and violated the principle of equality before the law.

Fears of forced assimilation and loss of minorities’ identity

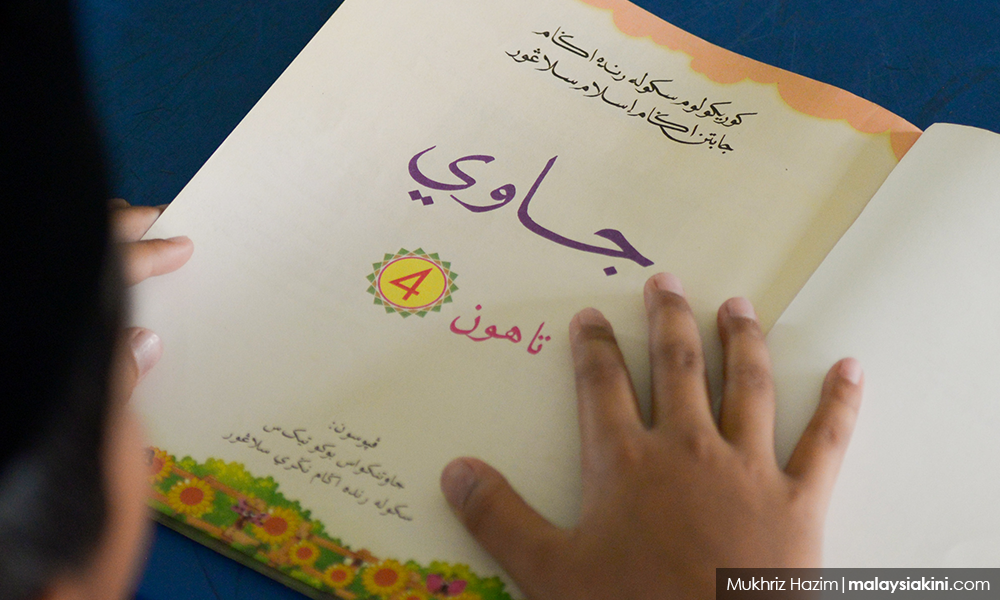

To the parents, the board of governors of the vernacular schools and the organisations objecting to khat being taught, the issue involves a deeper significance than just learning three pages of Jawi writing or the bypassing of the schools’ board of governors for the teaching of the subject.

It involves the lack of trust between the Harapan government and the ethnic minorities anxious to protect and preserve their culture, traditions, religions and language.

At the heart of this issue is the fear of forced assimilation of the minorities. Extreme emphasis on a homogeneous national identity – “one people one nation” and ethno-nationalist politics of exclusion have led to the “extermination” or “disappearance” of minorities’ culture, such as the German and French forced assimilation in the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine.

Other examples include the Ainu and Rkukyuan people in Japan and migrants of Gorguryeo, Balhae and Tungusic peoples in Korea.

In Malaysia, mother tongue education is the soul of each ethnic group’s culture. The vernacular schools have had a long and arduous struggle resisting the BN government’s call for their abolishment following the Barnes Report which was adopted in the Razak Report in the 1950s and the Rahman Talib Report in the 1960s. These reports advocated the abolishment of vernacular schools for the purpose of furthering national unity.

Paragraph 12 of the Razak Report on Education in 1956 says that:

“The ultimate objective of the education policy must be to bring together children of all races under a national education system in which national language is the main medium of instruction though it is recognised the progress towards this goal cannot be rushed and must be gradual.”

Section 21(2) of the Education Act 1961 provides as follows:

“Where at any time the minister is satisfied that a national-type primary school may suitably be converted into a national primary school, he may by order direct that the school shall become a national primary school.”

The minister may therefore by a stroke of the pen abolish and convert vernacular schools into national primary school. Although section 21(2) of the Education Act 1961 has been removed, the Education Act 1996 does not provide assurance vernacular schools will not be converted.

The Malaysian Education Blueprint 2013-2025 on the contrary states that the government still aspires to achieve the “ultimate goal” proposed in the 1956 Razak Report to convert the vernacular schools into national schools in the following passage:

“By 2015, the ministry will develop a comprehensive roadmap for the voluntary conversion of government-aided schools into government schools… The ministry recognises that many government-aided schools such as national-type schools, mission schools, conforming Chinese and religious schools are a critical part of the identity and cultural heritage of the diverse groups that make up Malaysia. Therefore, in encouraging the voluntary conversion of government-aided schools into government schools, the ministry will take special care to maintain the existing governance structure, identity and heritage of these schools” (MOE Blueprint 2013-2025 page 7-17)

In the light of this declared ultimate goal, the vernacular schools have exercised strict vigilance not to permit the BN government intervening into their curriculum for fear that any inroad will lead to the opening of the floodgates of conversion.

The lack of trust in the Harapan government arises from the events of the past 18 months. Despite the promises in its election manifesto, the government has repeatedly advocated the supremacy of narrow ethno-nationalist interests over universal human rights values and international commitments.

The minority groups’ reaction to the khat issue reflects the concerns arising from growing racism, xenophobia, and ethnic dominance. This stems from the avowed intention of a Harapan government seeking to win the support of the ethnic dominant group by playing on the deepest fears of the people and reification of the unfounded colonial stereotypes of the different races.

It is time to review this policy on the conversion of vernacular schools based on the reality that we are a multi-cultural country. Social cohesion can only be achieved by inclusiveness. The idea of “the melting pot” in which members of minority groups are expected to assimilate into a dominant culture does not work.

Multiculturalism is the only way to respond to the challenges of cultural and religious diversity. The members of minority groups can co-exist and enrich society by maintaining their distinct identities and culture.

The recommendation to abolish vernacular schools in the Barnes Report in the interest of nation-building and fostering national unity must be viewed from the perspective of the colonial imperialist ideology of that time. The colonial masters believed in the divine right for the subjugation by a superior race of inferior Asian and African races. The white man’s burden.

This has been scientifically proven to be completely false. The idea of national identity current at that time was ethnonationalism.

The core of the ethnonationalism idea is that nations are defined by a shared heritage which includes a common language, a common faith and a common ethnic ancestry. Ethnonationalism draws its emotive power from the notion that members of a nation are ultimately united by ties of blood and soil.

The central tenets of ethnonationalism belief are that nations exist, that each nation ought to have its own state and that each state should be made up of the members of a single ethnic group. Such beliefs have led to two world wars, the holocaust, ethnic cleansing and forced deportation of minority groups.

The more appropriate model of national identity for then Malaya is civic nationalism. That is all people who live within a country’s borders are part of the nation, regardless of their ethnic, racial or religious origins.

Malaya and now Malaysia is not and cannot be a homogeneous ethnic nation. We are a multi-racial and multi-cultural country. This is a fact. This is the reality. It cannot be denied. It cannot be ignored. It cannot be circumvented. Whether we like it or not we must learn to live with each other. We must learn to live in a shared society. There is no other alternative.

Many multi-ethnic countries have done it. Post-apartheid South Africa adopted the unifying image of a “Rainbow Nation” coined by Archbishop Desmond Tutu to influence social inclusion policies. Canada and Australia have accepted multiculturalism as the national doctrine: “The Australian government’s vision of a socially inclusive society is one in which all Australians feel valued and have the opportunity to participate fully in the life of our society.”

Similarly, Indonesia’s tradition of recognising its multicultural heritage has made the Muslim majority tolerant of minority religions and ethnicities. The preamble to Indonesia’s 1999 law #39 on human rights recognises that “besides basic rights, humans also have basic obligations to one another and to society as a whole, with regard to society, nation and state.”

This is an eloquent rendering of social solidarity under the five principles of Indonesia’s Pancasila.

We, in Malaysia also have our Rukun Negara and slogans like “Unity in Diversity.” However, only lip service is paid to them. Harapan is aware of what needs to be done to right the wrongs but has discarded them in favour of continuing failed policies. If the BN regime was guilty of stealing the people’s money, then the Harapan regime is guilty of stealing the people’s trust.

Courage to defend human decency

To address the khat issue, it is imperative for the Harapan leadership to reinstate the basic principle of social behavior – stop the explicit discriminatory appeals and policies. Stop the calls for racial discrimination, instigation of ethnic hatreds and race baiting conduct. There is no place for the tolerance of intolerance. What is required is the courage to fight bigotry and defend the basic norms of human decency.

The Harapan leadership must uphold and apply the basic principle to respect the dignity of every individual, respect for human rights and the rule of law. No ethnic group either the majority or minority has the license to ignore the rights of the others. While each individual is entitled to express his own identity and aspirations, this must be done in a way that accepts the dignity and rights of the others. There cannot be allowed any form of discrimination, marginalisation, deprivation or lack of equitable opportunity for all.

The Harapan leadership needs to assure the Malays that the preeminence, Malays enjoy as the demographic majority in terms of Malay language being the national language, the special rights under Article 153, the national culture, symbols and institutions, are constitutionally guaranteed and immutable. Such preeminence will not be affected nor diminished by accommodating and preserving the minorities’ culture, language and traditions. It is not a zero-sum game.

Being inclusive means the majority and minority may seek to have core aspects of their cultural identity-preserved and allowed to evolve. Neither has a unilateral right to impose upon the other in a way that the other identity is not allowed to co-exist.

If individuals and peoples are not able to express themselves in their language, enjoy their culture and traditions and pursue their aspirations, they will not live freely nor fulfil their dreams. As such they are a loss to the potential of our society.

The Harapan leadership must reject attempts to build Malaysia into a homogeneous society in which difference is discouraged or even forbidden. If we are not able to accept difference and learn to understand our fellow citizens and do not engage with the other, we are building barriers which will fester and lead to a social disintegration with devastating consequences.

Harapan leadership must act immediately. They must take concrete steps to achieve social cohesion and inclusiveness by creating Malaysia to be a country where it is safe for differences. There is no other option if we are to avoid a country continually wracked by identity-based tensions, inter-ethnic divisions, inequality and injustice.

Ultimately, the Harapan leadership must argue explicitly for ethnic tolerance and that this is a matter of basic human decency.

WILLIAM LEONG JEE KEEN is a PKR member and Selayang MP. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.