Focus Malaysia:

Mahathir’s great conspiracy game

by Dennis Ignatius

As the power struggle continues, more and more details are becoming available about the events surrounding the fall of the Pakatan Harapan (PH) government and the appointment of Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin as prime minister. It is a stunning tale of treachery and betrayal the likes of which we have not seen before.

Though all the key actors are, of course, putting their own spin on the revelations, one thing is abundantly clear: Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad – and Mahathir alone – stands at the epicentre of it all. Far from being the victim of a devilish plot, this is a conspiracy with his fingerprints all over it.

Remember, Mahathir returned to office in 2018 with everything going for him – a popular mandate, a comfortable majority in Parliament, and perhaps the broadest multi-ethnic support ever enjoyed by a prime minister in modern times. No other leader was better placed at the time of his swearing-in to unite the country, institute much-needed reforms and position the nation to fulfil its true potential.

But for Mahathir, being Mahathir, it was not enough. With the benefit of hindsight, a convincing argument can now be made that he returned to Putrajaya with an agenda of his own that was clearly at variance with that of his other coalition partners and inconsistent with the promises he made in the heat of the election campaign.

Mahathir’s agenda was four-fold – stymie Anwar’s ambitions to succeed him; limit the influence of the DAP which he felt had grown too powerful; isolate his enemies within UMNO; and build a new Malay powerhouse to replace UMNO as the dominant political force in the country.

And so, while others in PH were busy with the reform agenda, Mahathir played his great game. He repeatedly vowed to step down (at some unspecified date) but continuously cast doubts about Anwar’s suitability to succeed him. Nothing Anwar could have done – short of retiring from politics – would have made any difference. Mahathir was never going to allow him to become prime minister.

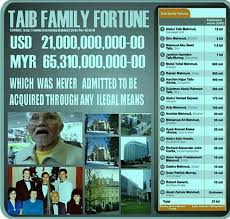

At the same time, he went after Najib, Zahid and select UMNO leaders on charges of corruption, money laundering and abuse of power, determined to finish them off politically. Of course, they deserved the special attention of the attorney-general’s office but they were by no means the only ones who warranted special attention. Other leaders with equally sleazy records and a string of scandals attached to them were given a free pass because Mahathir needed their support to forge his new political machine.

Even as he went all out to demolish his principal adversaries in UMNO, he assiduously courted UMNO MPs and its rank and file members, hoping that he could instantly grow his party with UMNO crossovers. While he might lament the plague of frogs that recently did him in, he himself encouraged it when it suited him. He cared little that the culture of corruption ran deep within UMNO or that they did not share PH’s enthusiasm for reform and good governance; numbers were all that mattered to him.

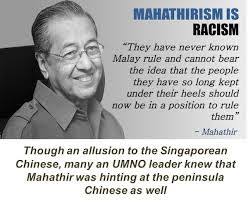

The hook that he used to try to persuade UMNO and PAS members to join his cause was, of course, Malay supremacy. He took to complaining, for example, that Malay disunity obliged him to give away senior cabinet positions to non-Malays. About the same time, his son complained that there were too many non-Malays in Parliament. In October 2019, Mahathir upped the ante by surreptitiously sanctioning the Malay Dignity Congress where he joined UMNO and PAS leaders as well as PKR’s Datuk Seri Azmin Ali to push the Malay supremacist agenda.

All this is, of course, history now. Or is it? Mahathir has never been known to walk away from a fight. Indeed, he is never more focused or more deadly as when his back is against the wall. As well, despite all that has transpired, he still stands astride the political scene, a colossus to be feared. His threat to destabilise the PN (Muhiddin’s Perikatan Nasional) government to the point of collapse is not something to be taken lightly. And they all know it.

The question now – as conflicting and fast-changing reports about shifting allegiances dominate headlines – is, what is Mahathir’s agenda? Is he seeking to return to Putrajaya as head of the old PH construct replete with a fresh commitment to the PH manifesto or as head of some new configuration that will allow him to continue his great game?

Anything is possible but before anyone starts salivating about the downfall of Muhyiddin (as joyous an occasion as that would be) and the return of Mahathir, they should ask themselves whether Mahathir is going to be a reformer or a reactionary. If it’s the latter, we might all be better off giving Muhyiddin enough rope to hang himself while preparing for GE15 (the next general election) than giving Mahathir another chance to play his great game. - June 3, 2020

Dennis Ignatius is a former ambassador

Mahathir’s great conspiracy game

by Dennis Ignatius

As the power struggle continues, more and more details are becoming available about the events surrounding the fall of the Pakatan Harapan (PH) government and the appointment of Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin as prime minister. It is a stunning tale of treachery and betrayal the likes of which we have not seen before.

Though all the key actors are, of course, putting their own spin on the revelations, one thing is abundantly clear: Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad – and Mahathir alone – stands at the epicentre of it all. Far from being the victim of a devilish plot, this is a conspiracy with his fingerprints all over it.

Remember, Mahathir returned to office in 2018 with everything going for him – a popular mandate, a comfortable majority in Parliament, and perhaps the broadest multi-ethnic support ever enjoyed by a prime minister in modern times. No other leader was better placed at the time of his swearing-in to unite the country, institute much-needed reforms and position the nation to fulfil its true potential.

But for Mahathir, being Mahathir, it was not enough. With the benefit of hindsight, a convincing argument can now be made that he returned to Putrajaya with an agenda of his own that was clearly at variance with that of his other coalition partners and inconsistent with the promises he made in the heat of the election campaign.

Mahathir’s agenda was four-fold – stymie Anwar’s ambitions to succeed him; limit the influence of the DAP which he felt had grown too powerful; isolate his enemies within UMNO; and build a new Malay powerhouse to replace UMNO as the dominant political force in the country.

And so, while others in PH were busy with the reform agenda, Mahathir played his great game. He repeatedly vowed to step down (at some unspecified date) but continuously cast doubts about Anwar’s suitability to succeed him. Nothing Anwar could have done – short of retiring from politics – would have made any difference. Mahathir was never going to allow him to become prime minister.

At the same time, he went after Najib, Zahid and select UMNO leaders on charges of corruption, money laundering and abuse of power, determined to finish them off politically. Of course, they deserved the special attention of the attorney-general’s office but they were by no means the only ones who warranted special attention. Other leaders with equally sleazy records and a string of scandals attached to them were given a free pass because Mahathir needed their support to forge his new political machine.

Even as he went all out to demolish his principal adversaries in UMNO, he assiduously courted UMNO MPs and its rank and file members, hoping that he could instantly grow his party with UMNO crossovers. While he might lament the plague of frogs that recently did him in, he himself encouraged it when it suited him. He cared little that the culture of corruption ran deep within UMNO or that they did not share PH’s enthusiasm for reform and good governance; numbers were all that mattered to him.

The hook that he used to try to persuade UMNO and PAS members to join his cause was, of course, Malay supremacy. He took to complaining, for example, that Malay disunity obliged him to give away senior cabinet positions to non-Malays. About the same time, his son complained that there were too many non-Malays in Parliament. In October 2019, Mahathir upped the ante by surreptitiously sanctioning the Malay Dignity Congress where he joined UMNO and PAS leaders as well as PKR’s Datuk Seri Azmin Ali to push the Malay supremacist agenda.

When asked about the many racist statements that emanated from the congress (including calls for non-Malays to be excluded from key positions and the abolition of vernacular schools), Mahathir pointedly declined to condemn them saying only that it did not mean that such resolutions would be implemented. It was tremendously damaging to Pakatan’s credibility, of course, but it was a price he was willing to pay to build his dream political juggernaut.

By the time of the “Sheraton Move,” things were already well advanced towards the formation of a Malay unity government. All the principal players gathered at Mahathir’s residence on Feb 23 to finalise the plan to ditch PKR and the DAP in favour of an all-Malay administration.

The argument now being proffered by Mahathir – that he was unaware that Muhyiddin had arranged a meeting of party leaders at his home - is simply not plausible. As well, he is on record as saying that he told them that he needed more time to “consider” the matter (whether to leave PH). But what was there to think about? If he was as committed to PH as he says he was, he should have immediately said no and sent them packing.

Having failed to isolate Najib and to a lesser extent Zahid, Mahathir tried one last option – a government of technocrats under his leadership that would be propped up in Parliament by Malay parties but without their direct participation. He reckoned that the political landscape was by then so divided that he was the only acceptable candidate. As it turned out, it was a bridge too far for UMNO-PAS as well as the ambitious and unscrupulous men that Mahathir himself had nurtured and encouraged.

With the dye cast, there was no turning back. Muhyiddin, seeing an opportunity to grab the top job, jumped at it with the encouragement of UMNO-PAS (which had the most to gain from the move).

By the time of the “Sheraton Move,” things were already well advanced towards the formation of a Malay unity government. All the principal players gathered at Mahathir’s residence on Feb 23 to finalise the plan to ditch PKR and the DAP in favour of an all-Malay administration.

The argument now being proffered by Mahathir – that he was unaware that Muhyiddin had arranged a meeting of party leaders at his home - is simply not plausible. As well, he is on record as saying that he told them that he needed more time to “consider” the matter (whether to leave PH). But what was there to think about? If he was as committed to PH as he says he was, he should have immediately said no and sent them packing.

Having failed to isolate Najib and to a lesser extent Zahid, Mahathir tried one last option – a government of technocrats under his leadership that would be propped up in Parliament by Malay parties but without their direct participation. He reckoned that the political landscape was by then so divided that he was the only acceptable candidate. As it turned out, it was a bridge too far for UMNO-PAS as well as the ambitious and unscrupulous men that Mahathir himself had nurtured and encouraged.

With the dye cast, there was no turning back. Muhyiddin, seeing an opportunity to grab the top job, jumped at it with the encouragement of UMNO-PAS (which had the most to gain from the move).

All this is, of course, history now. Or is it? Mahathir has never been known to walk away from a fight. Indeed, he is never more focused or more deadly as when his back is against the wall. As well, despite all that has transpired, he still stands astride the political scene, a colossus to be feared. His threat to destabilise the PN (Muhiddin’s Perikatan Nasional) government to the point of collapse is not something to be taken lightly. And they all know it.

The question now – as conflicting and fast-changing reports about shifting allegiances dominate headlines – is, what is Mahathir’s agenda? Is he seeking to return to Putrajaya as head of the old PH construct replete with a fresh commitment to the PH manifesto or as head of some new configuration that will allow him to continue his great game?

Anything is possible but before anyone starts salivating about the downfall of Muhyiddin (as joyous an occasion as that would be) and the return of Mahathir, they should ask themselves whether Mahathir is going to be a reformer or a reactionary. If it’s the latter, we might all be better off giving Muhyiddin enough rope to hang himself while preparing for GE15 (the next general election) than giving Mahathir another chance to play his great game. - June 3, 2020

Dennis Ignatius is a former ambassador

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.