EVER wondered where political parties get their money? And what they use it for? While skeptics may think that political parties just use their money for handouts and bribes, in fact, they also legitimately need money to carry out proper functions.

For example, political parties need to maintain their party machinery, conduct voter education and identify and train new candidates. During elections, they legitimately need to run operation centres, publish advertisements, print banners, hold public events, and incur other miscellaneous expenses such as transportation and accommodation.

Malaysian political parties, however, receive no state funding, unlike in other countries such as South Africa and Germany. There are also no requirements for political parties in Malaysia to declare their sources of funding. This means political parties are mostly left to their own devices to look for sufficient financing. With this in mind, how have Malaysian political parties been funding themselves, and how has the financing of parties influenced the political landscape?

Rich parties, poor parties

Political parties such as Umno traditionally relied on membership fees and donations from private individuals, as documented in Transparency International (TI)-Malaysia’s new bookReforming Political Financing in Malaysia, launched in May 2010. Over the years, however, Umno became more reliant on its investments and its business interests through ownership of corporations and shares.

TI’s book describes how Umno’s membership base changed considerably over the years. “In its early years, about half the members were teachers and another quarter was from the civil service,” it said. “However, by 1987, the number of teachers had been reduced to about a fifth of the membership, and the majority is now made up of business [figures], entrepreneurs and corporate figures.”

Tengku Razaleigh (Wiki commons)

Former Umno treasurer Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah revealed to TI that Umno was initially receiving funds from coalition partner MCA, which was then more connected to the business world. Razaleigh recounted how he was tasked with finding investments for Umno to ensure the party’s financial independence. He also acknowledged the existence of a covert Umno political fund which academic Barry Wain said was worth RM88.6 million in 1984.

Umno’s assets have grown considerably since then. Former Umno president and Prime Minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad told TI that when he stepped down in 2004, he handed his predecessor Tun Abdullah Ahmad Badawi RM1.4 billion worth of property, shares and cash.

TI also interviewed current MCA president Datuk Seri Dr Chua Soi Lek, who said the MCA profited from The Star, which contributes about RM50 to RM60 million annually to the party’s income. TI estimates the MCA’s current assets to amount to about RM2 billion.

“No money to invest”

TI also interviewed Pakatan Rakyat members, who painted a rather contrasting picture. When asked about the party’s investment, DAP national publicity secretary Tony Pua answered thus: “The only thing close to commercial that DAP does is own properties … in some cases they are rented out so there are some rental incomes here and there. It is marginal … We don’t have anything to invest. There is no money to invest, so we don’t have ventures.”

PAS’s Kamarudin Jaafar also said the party had no business venture or any corporate enterprise. “If we have properties, it is for our own use,” he said.

TI’s research indicates that Pakatan Rakyat parties still depend largely on grassroots support. They raise funds through a combination of membership fees, fundraising dinners, donations, publications and forums. Additionally, the DAP’s elected representatives are required to contribute a portion of their official allowance to the party coffers.

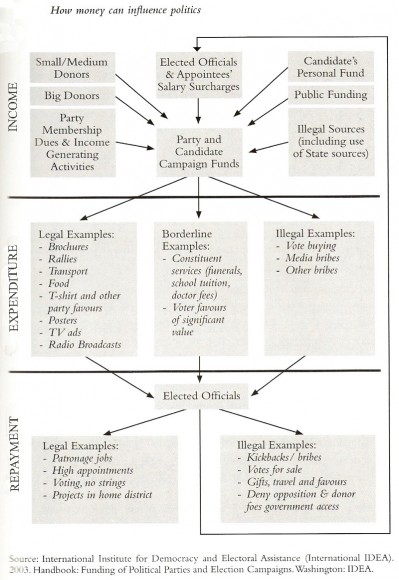

'How money can influence politics', from TI's book: Chapter One: Introduction, page 23 (Click on image for full view)

Broader phenomenon

So how did Umno, the MCA and other BN parties such as Parti Pesaka Bumiputera Bersatu Sarawak (PBB) accumulate so many assets compared with their comparatively impoverished Pakatan Rakyat compatriots?

TI says that money politics goes beyond buying votes during elections and is actually a much broader phenomenon. It documents how Umno, the MCA and MIC were all heavily involved in business, creating abundant opportunities to “[strengthen] the nexus between politics and corrupt money.”

“Business[people] or wealthy individuals with vested interests are eager to give money to politicians in return for securing business favours,” the TI book says. Moreover, it continues, the fact that contributions can be made covertly allows vested interests to control political parties and exert undue pressure on public policies.

As the cost of political campaigns and party activities increases with rising inflation and a growing population, having adequate funding becomes crucial in determining who will emerge victorious in an election. In such an environment, the pressure on PR state governments to use whatever connections and resources to help increase party funding must be intense.

The way forward

What changes must be instituted if we are to prevent money politics from swallowing Malaysian democracy whole?

TI’s book gives 22 helpful recommendations, a few of which are summarised below.

TI’s book gives 22 helpful recommendations, a few of which are summarised below.

![]() Require all political parties to disclose sources of financing and expenditure

Require all political parties to disclose sources of financing and expenditure

The public should be given complete access to political party accounts. Individual and corporate donations should all be subject to scrutiny to determine whether the government is favouring its big donors in the awarding of projects.

![]() Limit the amount of money an individual can donate

Limit the amount of money an individual can donate

In the UK, a cap of £50,000 on individual donations was proposed. The rationale is that this will decrease the possibility of political parties becoming beholden to wealthy individuals or organisations. This should also push political parties to solicit funds from a wider, more democratic base.

![]() Introduce direct state funding for political parties to finance their activities

Introduce direct state funding for political parties to finance their activities

The assumption is that once public money is involved, accountability will increase. State funding also levels the playing field by ensuring that not only the wealthy and well-connected can contest in elections. Funding can also be provided in kind.

In the UK, for example, parties get free air-time on state-owned media. The opposition also requires funding for administration costs to level the playing field since the government has the publicly funded civil service to help them.

![]() Empower the Election Commission (EC)

Empower the Election Commission (EC)

At the moment, the EC only has limited powers to scrutinise election expenses. It should be made truly independent of the ruling party and be given qualified personnel such as accountants to audit and verify the election expenses accounts submitted by representatives.

These are just four baby steps, which, if implemented, would already take us a long way towards better transparency and accountability in political financing than what we have now. Political parties on both sides, however, may not have the impetus to push for these reforms as it may cut off important streams of income for them. The task of calling for these reforms is therefore up to us, the electorate.

Otherwise, as Datuk Seri Dr Rais Yatim once said in relation to the Umno elections, if money politics takes further hold, it might be better to just have a tender system so that anyone who contributes the highest amount can be a leader.

courtesy of Nut Graph

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.