MALAYSIA’s internet community has been buzzing with the 2 Nov 2012 arrest of Ahmad Abdul Jalil for allegedly posting insulting remarks about the Johor sultan. Ahmad was remanded for three days and then rearrested for another three before being charged under the Communications and Multimedia Act. He says he was kept in uncomfortable conditions and insolitary confinement during his remand and questioned for eight to nine hours daily until his release. The police also searched his family home. On top of that, the police are currently investigating Malaysiakini and The Malaysian Insider for criminal defamation over coverage of the issue.

Online discussions have centred around the laws used to hold Ahmad, particularly the Sedition Act, and how posting comments on royalty could land someone in jail. The Nut Graphspeaks to political scientist Wong Chin Huat on the monarchy’s role in today’s world and how they are relevant and useful to democracy and the people.

TNG: What is the monarchy’s role in today’s modern politics?

In general, monarchies are still relevant in democracies or modern polities but they must be able to prove their worth. Once, the argument was simply the “divine right” theory. Royalty were chosen by heaven to rule – a common feature across many civilisations from Christian Europe to Hindu polities in India and Southeast Asia, to Imperial China and Japan.

An interesting exception is Islam, where hereditary monarchy was a much later invention by the Umayyad Dynasty. This happened after the deaths of the Prophet Muhammad and the first four rightly-guided Caliphs, the Khulafa Al-Rashidin, who were elected by their peers.

The justification for a particular clan or bloodline monopolising the highest public office is genealogical. If your parent is ruler, then you have the material to be a royal head, more than anyone else, whether by nature or nurture. And if everyone accepts this, there will be peace.

In reality, the ablest prince or princess often lost out in the succession race. In some cases,endogamy or in-marriage among royals led to genetic defects and even extinction. Finally, as absolute power tends to corrupt, benevolent monarchs could renege into tyrants.

The weaknesses that arise would then open the door for challenges by another aristocratic clan or another monarch, resulting in bloody civil or international wars. In this sense, democratic election – counting heads rather than chopping heads – is a smart invention to phase out wars to determine the power struggles within a country.

How do you reconcile democracy with monarchy? How is the monarchy more than an appendix to democracy?

British constitutional authority Walter Bagehot offered a brilliant theoretical justification: thehereditary monarch reigns as the state’s figurehead (“the dignified”), while actual power rests with the elected head of government (“the efficient”).

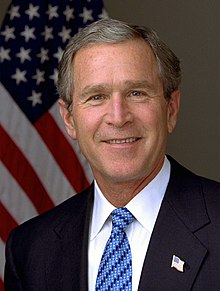

George Bush, Jr (Wiki commons

The underlying logic is actually very simple: multiparty democracy requires both talent and unity. The prime minister should be politically shrewd but need not be loved by all, while the monarch need not be super-brilliant but must be above the fray and well-loved.

In presidential systems, the head of state and the head of government is one and the same, the president. One only needs to look at former US President George Bush, Jr. to appreciate Bagehot’s wisdom.

Hence, the government must emerge competitively from elections but the head of state must instead be protected from competitive pressure. Thus, heredity becomes the best guarantee. This is the essence of the constitutional monarchy, which also provides the prototype for parliamentary government.

Prince Charles (Wiki commons)

Hence, monarchies can be perfectly relevant in multiparty democracies if the royals stay above the political fray. It has been warned that Britain’s Prince Charles may end the monarchy if he does not stay out of politics after becoming King.

What other common criticisms do monarchies need to overcome to survive republicanism?

Monarchies can become unpopular in at least three other circumstances. First, economically burdening the population; second, being emotionally disconnected from the population; and third, politically endangering national interests.

The first issue is simply one of value for money. Nothing can remain good when it is perceived as too expensive. King Juan Carlos used to be popular for favouring Spain’s democratisation in 1975 but by 2012, criticism has arisen over his lavish lifestyle. This perhaps explains why the Scandinavian and Dutch monarchies do not live luxuriously. Ultimately, monarchy must be affordable to be sustainable.

Secondly, for modern citizens, the monarchy must also understand and share how the people feel. The British monarchy was forced to allow a display of emotion after being criticised for being too cold on Princess Diana‘s passing.

Finally, no monarchy may survive if its interests are perceived to be against that of its population. That’s why the current British royal house changed its German name Saxe-Coburg-Gotha to Windsor when Britain was fighting against Germany in World War I. Closer to home, except for the Yogyakarta Sultanate, which supported the nationalists, all Indonesian monarchies were abolished after independence for supporting the Dutch. Just as loyalty is expected from citizens, the royals will find no forgiveness for any treacherous acts on their part.

What do you make of Thailand’s lèse-majesté charges against critics of the monarchy?

Old habits die hard. Criticising royalty was punishable by death in many countries. The crime is called sedition, which is still preserved in many countries including Malaysia. Of course, lèse-majesté provisions can also be hidden in other laws such as those regulating publications, broadcasting and the internet.

However, lèse-majesté laws won’t work for long. Nothing can stop an idea whose time has come. The best weapon against republicanism is to make the monarchy harmless to democracy. Compromising democracy and silencing criticism of the monarchy will only make them more vulnerable to republican undercurrents. Nepal was an absolute monarchy before 1990 and briefly after 2005, but where is the monarchy now?

The Narayanhity Royal Palace, former home of the Nepalese Royal Family. Following the abdication of the king and the founding of a republic, the building and its grounds have been turned into a museum. (Wiki commons)

Do Malaysian royal houses differ from other monarchies? What political roles do they play? Are they above the law?

At the federal level, our system is an elective monarchy, where royals elect the supreme head of state, normally among themselves. In that sense, we are similar to the contemporary United Arab Emirates and the ancient Holy Roman Empire but different from the hereditary ones.

At both federal and state levels, the Yang DiPertuan Agong and the states’ Malay rulers are theoretically constitutional monarchs. Unlike the figureheads who stay above the fray in the Bagehotian sense, the Malay monarchs are, however, tasked to protect the interests of Malays and Islam.

In theory, this could compromise their impartiality in the context of ethno-religious conflicts. In reality, free from electoral pressures to play communal champions, the Malay monarchs are traditionally more national than communal in their outlooks compared to Malay political parties. Anecdotes of friendship between Malay rulers and non-Malay commoners are abundant.

The political conflicts involving the Malay rulers are in fact not inter-ethnic but rather intra-ethnic, between them and Umno. Led by royals and aristocrats until Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad, the Malay nationalist party initially defended the royals and the feudal order opposed by the Malay leftists who were much influenced by republican Indonesia.

However, to the dismay of Umno’s leadership, Malay rulers intervened in its state politics, for example by dictating the choice of chief ministers. Royals may also compete with Umno politicians for business deals or logging concessions. For first commoner Prime Minister Mahathir, even his arch rival Tengku Razaleigh was a Kelantanese prince who enjoyed considerable support from some of his fellow royals.

The late Sultan Iskandar of Johor (Wiki commons)

In 1993, following an assault of a hockey coach by the late Johor sultan, the Mahathir administration amended the Federal Constitution to remove the rulers’ immunity. The rulers’ objections were successfully overcome with widespread public criticism against monarchical excesses whipped up by the mainstream media. Rulers who break the law may now be brought to a special court.

In reality, the royals’ power and actual immunity depend on their political bargaining power. This shrinks when Umno wins big and expands when Umno loses ground, as in 2008. The rise of the lèse-majesté charges and/or arrests since 2008 thus reflect the resurrection of royal influence on the federal authorities. And this is clearly not healthy for either democracy or the monarchy.

Why has Ahmad Abdul Jalil been charged? What is the ideal way to deal with such a situation so that it is seen as fair and just?

Ahmad is being charged under the Communications and Multimedia Act for posting offensive comments on Facebook against the Johor sultan. But nobody knows what the offensive comments were. This speaks volumes of the problem. The only justifiable way is to charge him for defamation, in which truth or fair comment can be a defence.

Any other way of charging him only undermines the popularity, if not the legitimacy, of the monarchy in a democracy. If this is the work of some monarchists, then the monarchy needs no enemies.

Wong Chin Huat is a political scientist by training and was a journalism lecturer prior to joining the Penang Institute, a Penang government think tank. If readers have questions and issues they would like Wong to respond to, they are welcome to e-mail editor@thenutgraph.com for our consideration.

You are so lucky to be a Malaysian, if Ahmad to be a siamese....i don't see any body can say anything...

ReplyDelete