by Khairie Hisyam

khairie@kinibiz.com

How did a little-known company, wholly owned by the government, come to be sitting atop a RM26 billion debt pile in a matter of several years? KINIBIZ traces the strange way Putrajaya’s private finance initiative vehicle raised its billions in funding.

Would you pay rental to yourself to use property that you already own for years – and have already long fully paid for at that?

That is exactly what Putrajaya is doing, having paid some RM5.77 billion in rental over the past two-and-a-half years to use 186 land parcels it already owns. And it will continue to pay another RM23.4 billion in total over the next 12 years or so.

The recipient? Pembinaan PFI Sdn Bhd, an obscure company wholly owned by the Ministry of Finance. “This is a left pocket to right pocket transaction,” said Kulim Member of Parliament and Public Accounts Committee (PAC) member Abdul Aziz Sheikh Fadzir at a media briefing in mid-March this year.

This strange and convoluted deal came about from the implementation of the federal government’s private finance initiative (PFI) initiative, first announced during the time of fifth prime minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, which sought to adopt a concessional procurement model widely practiced in other countries such as the United Kingdom and Australia.

However, there are a number of things wrong with how Putrajaya has proceeded with this procurement method. While the established practice for PFI projects to have the private sector source for their own financing, the Malaysian version sees the government providing the funds.

And these funds, totalling RM30 billion so far, were raised in a roundabout manner which critics say was intended to keep things off the government’s balance sheet. Transparency is lacking too: project awards are shrouded in secrecy and even appear unnecessary in some cases, with no known process for evaluation and accountability.

Most curious of all is the apparent intention of the entire PFI idea, which seems to provide contracts and concessions to bumiputera contractors. This raises questions on who these contractors are and whether they are benefiting from political connections in receiving these project awards.

In this part of the series KINIBIZ looks at the dodgy manner of Pembinaan PFI’s fund-raising and its implications as well as why Putrajaya is driving PFI in the wrong lane.

Putrajaya’s perverse PFI

The concept of PFI is not new, having seen wide practice in the United Kingdom and Australia between the 1980s and 1990s. However, the way Putrajaya had done its own PFI drive worryingly departs from the established norm.

Under the established practice for the model, the public sector basically contracts a private contractor to build and operate public infrastructure such as roads and hospitals. The private contractor is to find his own funding to do this and must meet the public sector’s specifications in terms of quality and timely delivery.

In return for the financing risk, the private contractor then receives regular payments under a concession, which normally range between 25 and 30 years in lifespan. A common condition of such concessions is that contractors must meet set quality and service delivery standards before they receive payments.

The idea is novel, premised on the notion that the private sector boasts superior efficiency over the public sector in terms of performance and delivery. A PFI undertaking also relieves some burden on the government’s budget–by stretching payments for public infrastructure over a longer time period, the government avoids forking out huge sums immediately, which eases cash flow and budget management.

In the words of Andrew Tyrie, the United Kingdom chairman of the Treasury Select Committee: “PFI means getting something now and paying later.”

But the UK PFI experience was not positive. An official audit found rampant cost overruns and late delivery. Patronage concerns and unduly expensive costs for public infrastructure also became pressing points. A particularly stark example of specifications unduly distorted to benefit contractors was when two hospitals in Coventry followed by a replacement hospital worth GBP410 million (RM2.15 billion) – both were originally slated for GBP30 million in upgrades and refurbishment by the public sector.

The Malaysian federal government was apparently undeterred by the UK experience and instead pursued a different, questionable approach. In awarding public infrastructure projects to selected private contractors through the PFI model, Putrajaya also provides the necessary financing to the contractors.

Therefore, the only gain by the public sector is the private sector’s supposed efficiency. The government still bears the financing risk. In turn, all the private sector needs to do is show up – yet some fail to do even that in the case of Putrajaya’s PFI drive. In other words the efficiency gain did not materialise in some cases.

The net effect: Not only does Putrajaya still need to foot a good portion of the upfront costs to have these public infrastructure built, it also bears the financing risk that should be borne by the contractors and independent financiers. And Putrajaya also built up billions of debts in the process in order to provide the financing.

A possible argument is that, given the intention of the PFI initiative to provide contracts to smaller bumiputera contractors, government financing is vital as smaller bumiputera players may not be able to raise sufficient financing on their own.

However, this does not hold water considering the PFI model entails concession awards kicking in after projects are completed. Essentially, the private contractors would have iron-clad income streams, locked in for a long number of years, that can be used to procure financing.

And if the private contractors cannot obtain financing even with concession awards in hand, this in turn casts a troubling question: should they have been awarded the projects at all?

Jumping through hoops

In any case, the perverse way Putrajaya had forged ahead with its PFI initiative had led to a convoluted lease-sublease arrangement in which the government essentially pays rent to itself.

The point: To indirectly pay for RM20 billion in borrowed funds that Putrajaya obtained as seed funding for its PFI drive.

The chain of events leading to this strange transaction goes back to a term loan from the Employees Provident Fund (EPF), which extended RM20 billion to Pembinaan PFI in August 2007. This loan was to be repaid in full, inclusive of interest capitalised, 60 months later unless another date was agreed to between the parties.

The chain of events leading to this strange transaction goes back to a term loan from the Employees Provident Fund (EPF), which extended RM20 billion to Pembinaan PFI in August 2007. This loan was to be repaid in full, inclusive of interest capitalised, 60 months later unless another date was agreed to between the parties.

And the interest rate was the rate of five-year Malaysian Government Securities (MGS) – published on Bank Negara Malaysia’s website – plus 0.5% per annum, applicable on successive six-month periods. The drawdown of this loan was staggered over a number of years and the funds were advanced to the government.

However, this loan was subsequently restructured multiple times after EPF consented to a restructure in a letter sent in November 2010. Eventually, in August 2012, Pembinaan PFI and the Federal Lands Commissioner (FLC) signed two agreements.

The first was a lease agreement for a period of 10 years and two days expiring June 16, 2022. Under this agreement the FLC would lease 186 land parcels to Pembinaan PFI in exchange for RM5.788 billion in total rental payment.

This follows a principal agreement signed in 2007 between Pembinaan PFI and the federal government, in which the latter agreed to get the FLC – the registered holder of the land parcels on Putrajaya’s behalf – to lease them to Pembinaan PFI in exchange for the RM20 billion.

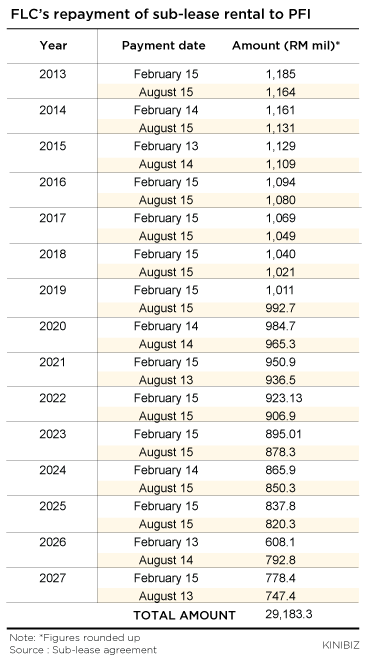

The second agreement was a sublease agreement through which Pembinaan PFI turns around and subleases the 186 land parcels back to the FLC. In return, the FLC would pay a total of RM29.18 billion in 30 twice-yearly payments from 2013 to year 2027.

What the transaction essentially does is create a revenue stream for Pembinaan PFI, albeit artificially. This allows PFI to service its loan from EPF, which had been restructured into one with an instalment payment plan.

However, in practical terms the federal government is paying for the loan taken out in 2007, even if the flow of funds is indirect and through a convoluted mechanism.

Hiding a liability

If the point of the convoluted exercise is to pay back a loan from EPF, why then is the government tying itself up in knots for such a simple undertaking? The answer may lie in another effect of the transaction – obscurity.

In mid-March this year, Prime Minister Najib Abdul Razak revealed in Parliament that Pembinaan PFI’s total debts currently stand at RM26.6 billion. This figure arose from two tranches of financing – the original RM20 billion term loan as well as a second RM10 billion financing in 2013.

For a government-owned entity, that debt figure is no trivial sum. The auditor-general’s report for 2013 listed Pembinaan PFI as having the third largest liabilities among government-owned entities as of end-2013, behind state oil giant Petroliam Nasional and sovereign wealth fund Khazanah Nasional.

Despite this recognition by the Auditor-General, however, Pembinaan PFI’s liabilities does not appear in Putrajaya’s list of contingent liabilities in years 2012 and 2013, according to information from the Accountant General’s Department. In perspective, this list includes entities such as controversial 1Malaysia Development Bhd (1MDB), Khazanah Nasional Bhd and government-linked companies such as Tenaga Nasional Bhd, among others.

However, in practical terms this is mere technicality. While not listed as a contingent liability for the government, the liabilities of Pembinaan PFI is still being repaid by the government in an indirect manner through the lease and sublease arrangement involving the FLC.

The implication is that by going through Pembinaan PFI to raise some RM30 billion in total, the government was able to do so without also adding RM30 billion to its list of contingent liabilities.

And the emerging purpose of Pembinaan PFI then was to raise additional funds off balance sheet. Interestingly PAC chairman Nur Jazlan Mohamed, in mid-March, called Pembinaan PFI an “innovative financing” method for the government in a strange interpretation of the term.

While questions dog the roundabout and dodgy manner of Putrajaya’s PFI financing, the billions raised by Pembinaan PFI had been silently spent over the years – with little transparency and accountability.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.