In the weeks following GE14, the focus has centred on developments at the national level, as Malaysians wait for a full cabinet and watch the new Pakatan Harapan government set in place its initial policies.

At the state level, there are equally important and transformative developments taking place, largely off the national radar. There are some worrying signs that greater attention needs to be placed on building the reform credentials of the Harapan government from below.

Varied tenuous patterns of state control

Harapan now holds power in eight states - Johor, Kedah, Malacca, Negri Sembilan, Penang, Perak, Selangor and Sabah (despite the outstanding legal contest for the chief minister position). The remaining states are held by PAS (Kelantan and Terengganu) and BN (Pahang and Perlis) with Sarawak now Pakatan-friendly under a new configuration of the Sarawak Parties Alliance (Gabungan Parti Sarawak).

Among Harapan states, there are broadly three political conditions. The first is a large majority coming with incumbency, as in the case of Penang and Selangor, and with a decisive victory as occurred in Johor. In these states, the main challenge is to accommodate different coalition partners (and in the case of PKR, factions) with positions and adequate representation. The new chief ministers in Penang and Selangor are also facing the need to come out of the shadow of their predecessors.

The second group of states are those that have slim majorities. These include Malacca and Negri Sembilan with a three and four-seat majority respectively. They face an Umno opposition, which at this moment is fragmented and inward-oriented.

All of the majority Harapan states are vulnerable to issues within Harapan itself. Beyond jockeying for positions, differences over race and religion have the capacity to divide the coalition and are especially impactful in states where Umno and PAS are likely to play on these factors.

Unlike the situation at the national level, where Sarawak’s Pakatan-friendly orientation has shored up Harapan’s more inclusive position on race and religion, this is not the case in many of the Harapan states and thus makes these states more vulnerable to the mobilisation of political division along racial and religious lines.

The third group are states where Harapan holds the majority of seats but this majority can be overturned by a coalition among opposition parties or a reconfiguration of different partners. Here, Harapan governments are balancing a combination of internal and external pressures, including continued inducements for defections. The potential for political instability in these states is real.

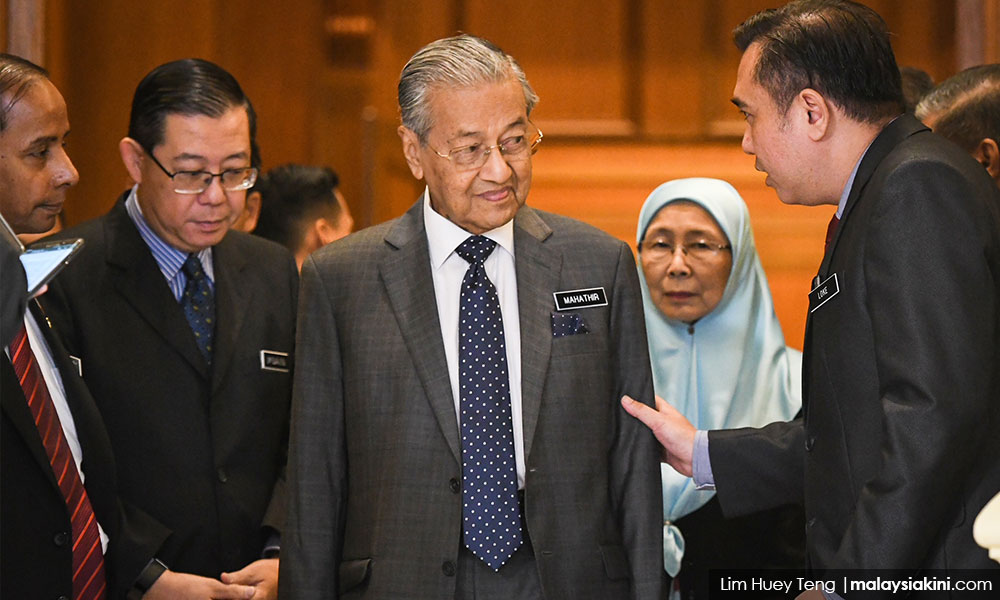

This is the case in Sabah, where Warisan is the largest party allied with Harapan to form government. Warisan (led by Shafie Apdal, photo) holds 23 seats, with Harapan parties holding eight seats, with a majority of two seats. Perceived unfair actions taken against Warisan partners in areas such as appointments by the federal government can potentially inadvertently contribute to instability in Sabah.

Perak and Kedah also fall into this category of possibly overturned majority states. In these two states, PAS holds greater political power. In Perak, Harapan holds onto 29 seats, with the BN at 27 and PAS at three, while in Kedah Harapan holds 18, with PAS at 15 and Umno at 3. In the last month, there has been considerable wrangling over the speaker and deputy speaker positions in Kedah, with the possibility of elections should there be an impasse.

The balance of power in Perak remains fragile and given the history of induced political turnover in the state, it is arguably the most vulnerable to a change in government.

Chief minister choice

It is also important to appreciate that legal decisions involving the case of the chief ministership in Sabah and election petitions across the country have the potential to shift the numbers in these majorities.

The sources of instability at the state level extend beyond managing numbers. Crucial is the choice of chief minister and the state leadership.

The royalty has played a pivotal role in deciding who should run the different states, from Selangor and Perak to Johor. This has placed constraints on the Harapan government(s). The royalty’s role has been prominent under the BN government as illustrated by the Terengganu crisis of 2014 and more recently in Perlis but is being more openly being discussed in the era of ‘new’ Malaysia.

At issue are not just concerns for representation, race and religion and economic interests, but the democratic fabric of Malaysia. Increasingly there is greater disgruntlement with royal interventionist positions.

This is especially the case in states where a sultan’s veto power has been seen to reduce the stability of a Harapan government or led to choices that are seen to bring into power a perceived less experienced candidate. The open criticism of the choice of new Selangor menteri besar, Amirudin Shari, is illustrative of some of the disgruntlement, although in this case these complaints are also reflective of the different factions within PKR.

Capability, qualifications and the reform orientation of the new state leaders are at the core of concerns surrounding the leadership of Perak and Johor.

The Perak menteri besar, Ahmad Faizal Azumu from Bersatu, whose fiasco in the handling of the Hari Raya open house in a theme park earlier this month was criticised, has yet to properly answer questions about the veracity of his academic qualifications. He is seen to be closer to Umno than to Harapan, coming from a traditional Umno warlord family. While still early days, his leadership to date has failed to broach any of the scandals of the previous Zambry Abdul Kadir government and is evoking serious criticism from the ground.

The choice of Osman Sapian, the now Bersatu former Umno three-term state assemblyman from Kempas, to be the menteri besar of Johor also signals the persistence of status quo politics at the state level. Osman’s choice has been seen as possibly limiting reform and not actualising the leadership potential for Johor at the state level.

The expectations in Johor are especially high, given its economic and political importance and the decisiveness of Harapan’s victory. The choice of Osman has emboldened Umno who feel they can win the state back under Osman’s leadership and not evoked confidence among many Harapan supporters.

Reform from below and above

Decisions at the state level to date have showcased some of the ideological differences within Harapan itself, most notably the connection to Umno and its style of patronage politics. In other states such as Malacca, the early patronage to Harapan members, some of whom are not qualified for the positions in state-linked companies they were given, also raised eyebrows.

States play a crucial role in governance, and if reforms in Malaysia are to gain traction they need to happen at the state level as well. The same clean-up and oversight of government-linked companies touted by Harapan leaders at the national level should be paralleled at the state level, especially given the link between state governments and national scandals as occurred with Terengganu and 1MDB.

A failure to address reforms at the state level opens up Harapan for criticism and has the potential to undercut any reform at the national level. Keep in mind the greatest vulnerability the Harapan governments face is a loss of confidence among the electorate. It is at the state level, in vital areas of land development and social service management, that many witness first-hand abuses of power and corruption concerns.

Political transitions are not easy, especially given the resistance to these transitions and how vulnerable many of the state governments actually are to political turnovers and status quo politics. In 2008, it took some time for the Selangor and Penang governments to find their footing and this will likely be the case for the new Harapan state governments as well, and arguably pressures for reform were also curtailed.

In this era of ‘new Malaysia’, the need for capable and reform-oriented leadership at the state level will be essential to bring about the changes needed to improve governance.

Unlike in the past, however, the federal government has the power of the purse to encourage greater reforms at the state level and can set important governance examples. Working collaboratively with state governments to move out of status quo politics toward reform from above and below is essential to reducing vulnerabilities of Harapan states.

A failure to do so puts these governments at risk and deepens the challenges for the federal government itself.

BRIDGET WELSH is an Associate Professor of Political Science at John Cabot University in Rome. She also continues to be a Senior Associate Research Fellow at National Taiwan University's Center for East Asia Democratic Studies and The Habibie Center, as well as a University Fellow of Charles Darwin University. Her latest book (with co-author Greg Lopez) is entitled ‘Regime Resilience in Malaysia and Singapore’. She can be reached at bridgetwelsh1@gmail.com. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.