HISTORY: TOLD AS IT IS | This article, as part of the repeated calls for refreshing Malaysian history along inclusive lines, will hopefully serve as a reminder that the historical contributions of marginal groups are just as important in the development of our nation as the other dominant ethnic groups.

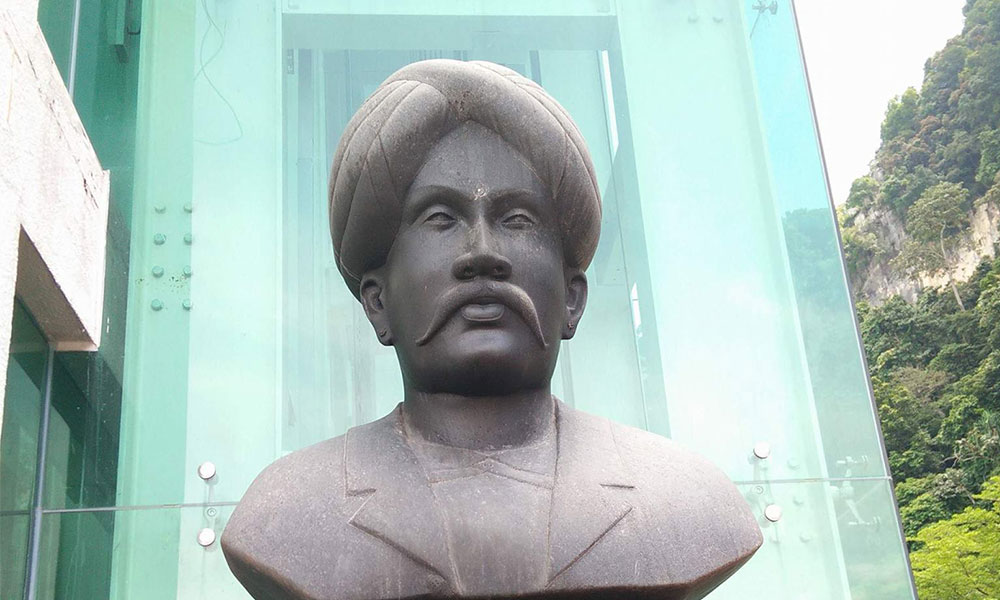

Despite being one of those close acquaintances to the British colonial circles in the early history of Kuala Lumpur, Kayarohanam Thamboosamy Pillai, born in Singapore in 1850, has been a largely ignored and under-appreciated Tamil elite. He was one of many historical figures, most of whom are similarly overlooked, who played remarkable roles in breaking down racial barriers in the development of our nation.

Pillai earned great respect among British administrators and individuals of all other races, including European high social elites, Malay aristocrats, Chinese capitalists, and of course, Indians from the upper and lower echelons.

His ability to win and hold unwavering respect during his days of engaging with all of these social classes, particularly in Kuala Lumpur between 1874 and 1902, was a significant achievement in and of itself. It was the time after the British had officially intervened in Malaya, ushering in the creation of a racialised social hierarchical structure, the legacy of which can still be seen today.

During his active social and professional years in Kuala Lumpur, Pillai climbed to establish considerable rapport with elite groups, particularly among the capitalist and colonial administrative classes, as well as with non-elites. To some, he was a dedicated public servant, an industrious businessperson, and a respectable elite. To many, he was a role model whose accomplishments went beyond simply carving out a niche for himself.

It was not an easy feat, however, for him to establish an outstanding reputation and eventually be regarded as an unofficial leader, or the "kapitan", of the Indian community in Kuala Lumpur.

Pillai's social influence stemmed in part from his inherent abilities, virtues, and a passionate temperament for rising through the ranks from his youth. It grew steadily over time, thanks in large part to his English fluency, an essential trait he acquired in Singapore where he was born and attended the elite Raffles College.

He clearly excelled in his command of the English language, allowing him to demonstrate his competence by initially working with a British legal firm and colonial administrators in Singapore. Much of this was evident during his time as a clerk at the legal practice of Rodyk & Davidson. One of the firm's partners, James Guthrie Davidson, was not only one of his personal friends, but he would also become the first British Resident of Selangor in 1875.

Pillai’s destiny, however, would lead him to Selangor, and eventually to Kuala Lumpur, the capital of the Federated Malay States, where he would attain prominence. His presence in Kuala Lumpur was not only timely but also necessary because the British residential administration desperately desired to staff its department and other subordinate offices with English-speaking clerical personnel to ensure day-to-day administration took place without unnecessary hurdles.

Davidson, of course, would have witnessed Pillai's white-collar proficiency firsthand while the latter was one of his legal staffers in Singapore, and he would also have been an earwitness to the latter's naturalness in conversing in English. It was thus unsurprising that after being appointed as the Selangor Resident, Davidson would appoint Pillai as the acting state treasurer not once, but several times.

Pillai was required to assess financial plans and approve cash for Kuala Lumpur’s development projects. This was not an easy assignment, as proven by one of his most significant and difficult tasks in the 1880s: dispersing funding for the construction of Kuala Lumpur. It was also his duty to weed through numerous applications from merchant capitalists requesting state financial assistance.

At times, Pillai felt enormous pressure from some impatient applicants due to the hurry and frenetic scramble among prospective investors to open up raw material production in the state. Some forced him to speak with the Resident in order to accelerate the loan application. There was even an occasion where an investor tried to bribe Pillai, but Pillai refused and instead felt obligated to report it to the treasurer.

Pillai's sense of duty and integrity likely led to his next appointment as a member of the Sanitary Board, the urban authority established by the colonial administration to monitor the early phases of Kuala Lumpur's development. Here, too, Pillai was diligent, since he never missed a single board meeting and was a vocal participant.

Batu Caves foundation

Pillai also had the opportunity to gain an intimate glimpse at the lives of the Tamil working class as a colonial-appointed labour recruiter. In fact, he may go down in history as the man who brought the first group of Tamil labourers to the state to work on railway construction and public projects.

Although he was later forced to take harsh actions against some of the labourers who attempted to flee elsewhere, ostensibly due to bad working conditions, he was not an exploitative or oppressive labour overseer in the manner of a "kangani" (foreman in Tamil). He even utilised the fines he collected from such labourers to construct a temple on Jalan Tun HS Lee in Kuala Lumpur.

Pillai's ability and competency in managing Tamil labourers, as well as his status as a trustworthy colonial elite, led to his unofficial recognition as the kapitan of the Indian community. He performed effectively in this role. During an outbreak of cholera, beriberi, and smallpox in Kuala Lumpur in the early 1890s, Pillai took on the responsibility of urging the labouring community to get vaccinated.

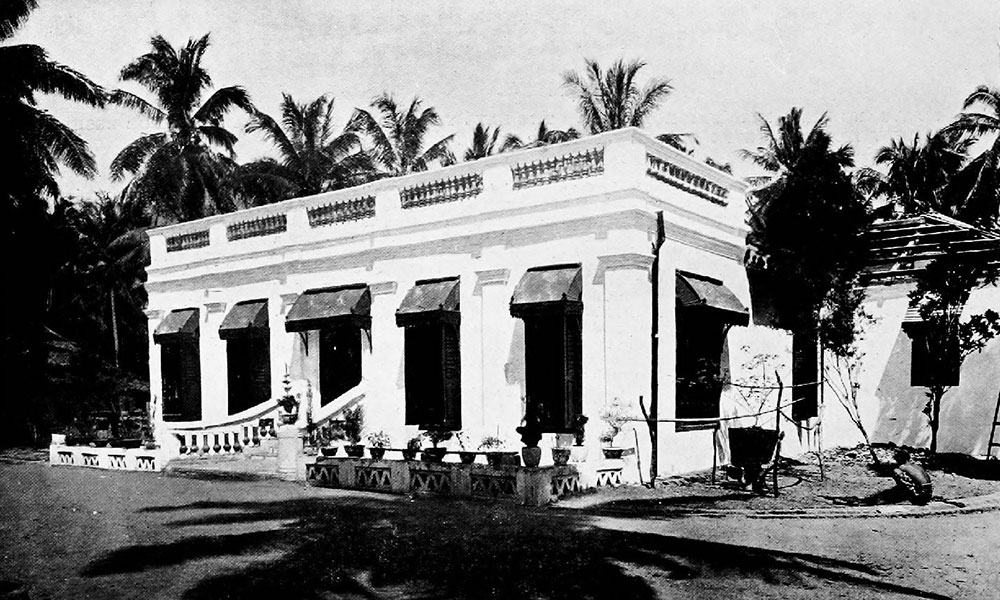

He also planned for a large-scale Tamil labour settlement at the heart of the town. The now-famous Mariamman Temple in Kuala Lumpur was founded by Pillai, who discovered the original site during a business trip and relocated it to its current location to allow the Indian community, including the working class, to practice religious activities.

His most visible contribution, however, would be the considerably more famous and internationally renowned Batu Caves dedicated to the Hindu deity, Murugan. The history of this specific devotional site is fascinating, as its foundational stones for building a small shrine of worship were literally laid by a group of Tamil labourers Pillai recruited to work at a nearby construction site. Pillai would then conceive it as a larger centre of worship.

Following his resignation from colonial service, he went on to undertake capitalist pursuits for the rest of his life, mostly as a road contractor, farm operator, mine operator, and landowner. Pillai, for example, was in charge of constructing the road that connected Kuala Lumpur and Rawang in 1892. It was so essential that the flood of labourers from outside Kuala Lumpur promoted further development of the town after it was built.

In 1890, he reportedly had hundreds of acres of coffee-planted estate in Selangor. But the most remarkable feature of his capitalist career was his profitable partnership with Loke Yew, also known as the “Tin Magnet”. They formed the New Rawang Tin Mining Company, which expanded tin ore output in Kuala Lumpur/Selangor by using – for the first time – an electric pump to generate energy. Pillai continued to invest in large-scale mining concessions through his collaboration with Loke Yew, the proceeds from which enabled Pillai to invest in other sectors such as railroads and rubber plantations.

Other distinguishing features of his life in Selangor were his embrace of Western lifestyles, such as dressing in European-style attire, participating in horse racing, and actively engaging himself with the high social elites in the Selangor Club, which he helped to establish. He was also exceptionally generous to the upper classes, as seen by his donation and establishment of the Victoria Institution in 1894, as well as his financial help to British officials.

Nonetheless, he was equally generous to the lower classes, as when he extended a helping hand to the Malays in Kuala Lumpur on numerous occasions, mostly financially, and when he converted his house on Batu Road in 1880 into an institution to teach Tamil language to the children of labourers.

Pillai's extraordinary journey was tragically cut short when he died in 1902, at the age of 52. His roles, contributions, and personal achievements should be recognised not just for their historical legacy, but also to bring to light more Pillais who have been veiled in Malaysian history.

SIVACHANDRALINGAM SUNDARA RAJA is an Associate Professor at the University of Malaya’s History Department. He is a well-known scholar in the field of Malaysian economic history, with numerous local and international research publications to his credit.

- Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.