Every month, heroes from Malaysia’s civil society rescue their fellow citizens from the horrors of modern slavery in scam compounds in Southeast Asia.

They do so without the publicity and search for fame.

On their rescue missions, they often save victims from other countries in the region, especially those from Indonesia who reach out to them because of the common language.

Currently, an average of 20 Malaysian trafficking victims are rescued monthly by civil society initiatives.

While middle bureaucrats in Malaysian embassies do their best to assist these efforts, the embassies lack an adequate budget to even provide pocket money for victims whose lives have been irreparably harmed.

That the trafficking victims have been classified as “criminals” for being forced into criminality through electrocution, extortion, and physical torture to engage in scamming has blinded authorities to the devastating conditions being faced.

The horrors that Malaysian victims have experienced cannot be underestimated.

Sadly, some authorities are revictimising those who have been scammed by labelling those forced into criminality as “criminals”.

A serious problem

Currently, tens of thousands of people are being held in scam compounds across the region. It is estimated that there are at least 17,000 people enslaved in the southern Myanmar-based scam compounds alone.

While Malaysian embassy authorities have rescued over 800 victims across the region and civil society organisations such as the Malaysian International Humanitarian Organization have rescued 350 victims since 2022, the overall number of Malaysian held captive is much higher.

Malaysia remains a key target of syndicate job scam/human trafficking operations. Reports put this number in the thousands.

For example, of the 261 victims released this month in the KK Park and Shwe Kokko of the Myawaddy as a result of Thai pressure, 15 were Malaysians - six percent. This is just one of scores of compounds across the region.

The job scams target different groups of people, with recent trends indicating that Chinese Malaysians are being trafficked into Myanmar and Malays and other bumiputera communities, especially from Borneo, into Cambodia and to a lesser extent, Laos.

Victims used to be concentrated in places such as Kuantan, but current trends show a disproportionate number of job scam trafficking victims are from Sarawak, Sabah, and Johor.

There is still too much denial of how serious this issue is. Of particular concern are some parliamentarians who label a call for greater attention to this issue as “flimsy”, when their own constituents are being harmed and forced to scam other constituents in their constituencies.

Hundreds of thousands of Malaysians have been victimised by various online fraud scams with losses in the billions. Wealthier areas such as Petaling Jaya and other parts of the Klang Valley are particularly targeted.

The losses from citizens are in the billions of ringgit and rising; it is critical to understand that efforts to date have not stopped the problem from causing more harm.

With the liberalisation of visas for China nationals, there has been an increasing trend of Malaysia-based centres being used as hubs to defraud people through job scams.

Just this week alone, Malaysian police busted two job scam syndicates in Kuala Lumpur and Pulau Pangkor in Perak, confiscating millions.

These local centres are increasing throughout Malaysia, placing strain on law enforcement authorities to address the power of the global syndicates.

Learn from Thailand, Philippines, S’pore, and Indonesia

There are tangible steps that can be taken, with regional neighbours providing some examples.

First, a crackdown can make a difference, such as that in Thailand. Recent arrests by police of scammers in centres are a positive step.

It is important to appreciate that global scam syndicates move to places where they can operate, which means that Malaysian authorities need to maintain high vigilance and deepen crackdown measures.

To date, to my knowledge, there has yet to be any prosecution of those involved in job scam human trafficking. This involves tightening laws and showing through legal examples that these practices cannot be tolerated.

Steps were taken last year to strengthen penalties for online fraud, but legal remedies to tackle transnational crime are not being addressed holistically, especially through prosecution and conviction.

An important gap to address involves how scam syndicates are undercutting governance through corruption.

A good place to start is better regulation of online gambling, which has been a gateway for scam syndicates, as shown in the Philippines. The focus there has been on going after top guns rather than rounding up and deporting those working in centres.

A crucial area needing attention is better regulation of cryptocurrencies and greater controls of money laundering. Singapore provides lessons here on concrete measures to tighten regulations.

More needs to be done to help job scam victims after they have been trafficked. This involves creating a fund for embassies for assistance and shelters in the region and rehabilitation support once individuals have returned to Malaysia.

A key step is a more aware victim protocol that understands the damage of starvation, locking people in dark bunkers and handcuffing people to tables as they are forced to scam.

Indonesia has created a bureau to assist its citizens overseas in the foreign ministry. This could be replicated in Malaysia, as its embassies are facing this problem without enough resource support. More collaboration with civil society and academia can strengthen this effort further.

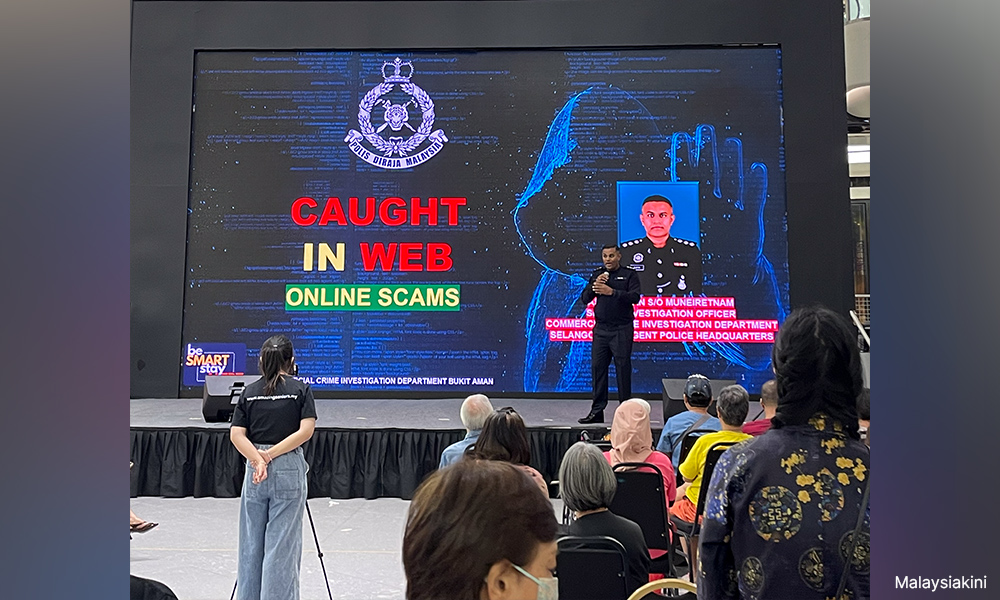

Finally, Malaysia can learn from herself, with one of the best online fraud awareness public awareness campaigns in the region, supported by an active media.

The need for education of young people on job scam risks needs to be ratcheted up in society as a whole. A targeted campaign for youth would also strengthen prevention.

Transnational crime remains one of the most serious regional and global threats. Malaysians are being harmed in increasing numbers. This harm can be ameliorated with better interventions and governance.

Malaysia has an opportunity as the Asean chair to do more - by being an example through measures at home and pushing for meaningful regional solutions.

It starts by recognising that not enough is being done, taking stock of measures that are working at home and abroad and having the political will to implement them.

For those interested in hearing about the Malaysian International Humanitarian Organization's rescue work, listen to Straight Talk Southeast Asia Season 3, Episode 7, also available on Apple podcasts and Spotify.

BRIDGET WELSH is an honorary research associate of the University of Nottingham’s Asia Research Institute, a senior research associate at Hu Fu Center for East Asia Democratic Studies, and a senior associate fellow at The Habibie Centre. Her writings can be found at bridgetwelsh.com.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.