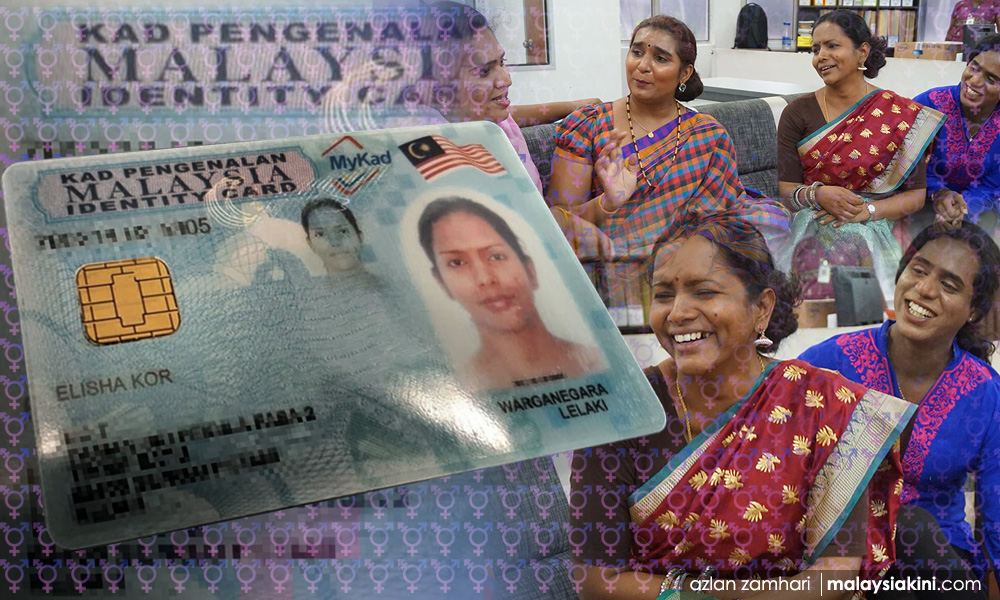

SPECIAL REPORT | In 2003, transgender activist Elisha Kor Krishanan went to the National Registration Department after completing her sex reassignment surgery in Thailand, hoping to change her gender on her identity card (IC).

She brought a number of documents based on the instructions given by the department, including her original birth certificate and a photocopy, an approval letter from the local doctor, and supporting document on her sex reassignment surgery.

However, just like many others in the transgender community in Malaysia, changing her IC gender remained an elusive goal for Elisha.

“I remember it was 2003. I went to the National Registration Department to change the gender status on my IC, but the officer said, ‘Cannot’. And I asked, why? He just told me to hire a lawyer, or go home, without giving any clear reasons."

“Yes, I failed to change my IC gender status and the last two digits on my IC… It ended up no matter how (much of a) ‘woman’ I am, others still call me ‘Encik’ (Mr) according to my official gender status," she said.

Sixteen years later, 39-year-old Elisha (left in photo) founded the Malaysian Public Health and Welfare Association (PKKUM) to provide assistance to marginalised and under-represented communities, including transgender people.

‘I don’t have a choice’

In August 2018, Elisha held a press conference at PKKUM’s Kuala Lumpur office to reveal the difficulties faced by the transgender community. However, only a few media outlets were in attendance. This was around the time that Pakatan Harapan leaders were debating whether transgender people should be allowed to use female toilets.

However, two weeks before the press conference, de facto Islamic Affairs Minister Mujahid Yusof Rawa had re-iterated his previous statement that the LGBT community's rights as citizens are enshrined in the Federal Constitution, which means they cannot be discriminated against at the workplace.

Elisha told Malaysiakini after the press conference, “People ask me why, why you become transgender? When do you decide to become like this? But all of those questions are not right… I do not have a choice.

“The gender status (on my IC ) means everything. Your actions have to, you know, sync with your gender… If not, isn't it like ‘senget’? (off-balance). ”

Elisha was born into a traditional Indian family. When she was young, her parents taught her that a boy should always behave like a boy. Thus, she would be corrected whenever she displayed seemingly unmanly behaviour.

“But my family will say, you are a boy. You have a ‘kukubird’ (penis). So you should be like this, like that... My family, they don’t have enough knowledge about trans people, they don’t know what is trans people, intersex… and they don’t have any doctor to refer to, and this is Malaysia,” she said.

When she was nine, she was only able to tell that she liked the colour pink better than blue, and preferred wearing skirts instead of jeans. But she had no idea what made her so different.

“When I was nine years old, I felt like I was different from my male friends. When they called me to join them to play, I felt shy. I felt so shy to mingle with them, but I could not properly express (myself) and tell (people) that I am different.”

“After some time, they (my parents) started to realise this child was special,” she said. Her family learnt to embrace her differences and began treating her like a daughter.

“We believe in Hinduism, and our religion accepts everyone’s special characteristics. If the kids are facing gender dysphoria (in Hinduism), they are able to change their sexual orientation.”

When Elisha turned 12, her family agreed to let her state her gender as ‘female’ for her first IC. However, she ran into problems when applying for her IC.

“...The officer refused to change (my gender) for me because my birth certificate was written as ‘male’. They said my gender (marker) is filled according to what is stated in my birth certificate, so it could only follow my birth certificate. I am not sure what the reasons behind this are. ”

Protecting oneself against bullying

Since Elisha’s gender was stated as ‘male’ in her IC, she was required to wear male uniforms to school. Meanwhile, she was allowed to dress like a girl at home.

Bullies became Elisha’s biggest nightmare throughout her five years in high school. Losing shoes, and suffering injuries from beatings became part of her daily life.

She ran as fast as she could every time the school bell rang, and asked her mother to wait for her in front of the school entrance.

“The teachers knew I was more ‘feminine’ compared to the others, but still, they would call me ‘Boy’. Every time when I was bullied, my teacher would say, ‘That’s your fault, you are a boy but act like a girl. That’s why people are laughing at you.’” she said.

“I didn’t know what to do and how to explain to them. The only thing I knew was this was not my fault, but what I could only do was cry, because no one understood my thoughts.”

After various incidents, she says that she “learned from mistakes” and how to protect herself by “isolating” herself from others.

However, Elisha experienced a similar pattern of unfortunate events even after finishing high school.

“All the bad things would repeat, every single time I started with a new circle, a new life. The same thing happened again when I started my first job, when I joined college.

“Psychologically... almost every day I have dilemmas, I am dealing with dilemmas, saying that I am not a man… and sometimes you will also convince yourself that it is fine, as long as you know you are a woman… but sometimes you will feel that your body and your brain are different. So, (I thought) something is wrong with my body.

“I tried to take pills to control my thoughts and all kind of emotions… After years, I found that sex reassignment surgery was the only way to make a change in my life.”

Seeking hope overseas

Elisha is not alone in her struggle to change her IC gender. There are nearly 30 people from the transgender community facing the same issue in her NGO.

Fifty-year-old Vasugi Amma is a PKKUM member who has experienced bullying and difficulties similar to Elisha’s. She decided to undergo sex reassignment surgery when she was 23 years old.

“I underwent sex reassignment surgery on July 13, 1998. I can remember it very clearly. Even if I forget my birthday, I will not forget the day I underwent the surgery. It's like being reborn, reborn with a woman’s body, living as a woman.

“My family couldn’t accept my ‘behaviour’... They cried every day, then I chose to go to Singapore when I was 16, to work part-time in a banana leaf restaurant. Singapore was more open(-minded) in the 1980s… More open, meaning that they were more inclusive when talking about sexual orientation,” Vasugi told Malaysiakini.

During the 1980s, Thailand was a more popular destination for the surgery compared to Malaysia, as the fees were cheaper and it cost around RM8,500. Nevertheless, she needed to save money for the surgery, and as such, it made sense to work in Singapore.

“The currency of Singapore is stronger than Malaysia’s, which means I am able to earn more and save more.

“I went there (Singapore) with a friend from Kelantan, and no one knew me in Singapore, and I started to dress like a woman. My boss was totally fine with it.

“Four years (at the banana leaf restaurant) were tough and the only thing I hoped for was to correct the ‘error’... The error means my sexual orientation,” she added.

‘Finally, I could live like a woman’

Three months after Vasugi completed the surgery, she went to the National Registration Department to change her name and have the patronymic “anak lelaki” (a/l) removed. She also wanted to change her gender on her IC.

She was told to bring along an affidavit, and approval letters from the doctor who conducted her surgery and a local government hospital.

“In the first month (after approving my application), they gave me a temporary IC, and after three months, I got my new IC. It was really convenient.

“After that day, they treat me like a woman… No one calls me ‘Encik’ when I go for the clinic, they will address me as ‘Puan’(Mrs). And they all call me nicely, like ‘Puan’,” she said, laughing.

“After all this, finally, I could live like a woman. And I was finally ‘back to normal’,” she added.

However, not everyone has been as lucky as Vasugi. She noticed that there were plenty of cases around her in which transgender people were experiencing difficulties after the government began tightening regulations to change IC details in the 1980s. Elisha is one such person.

In 2003, Elisha brought all the required documents to the National Registration Department to have her IC details changed after her surgery. However, without giving a reason for its decision, the department refused to change her gender status.

"They (the National Registration Department) only changed my name, so my name written in my IC is Elisha Kor, without ‘a/l’, but my gender column is still ‘lelaki’ (male), so I become ‘Encik Elisha Kor’. It’s both really funny and annoying."

After her application was rejected by the department, she was told to find a lawyer to apply for a court order to have her IC gender changed.

“The fees to hire a lawyer to get things processed is really expensive, I already paid almost RM16,500 to do the surgery, and now I have to prepare my lawyer’s fees.

“We trans people spend our whole lives (working) for only two things, one is to save money for sex reassignment surgery, the other is to save (money) for thousands of ringgit in fees for a lawyer in order to get the court order.

“I didn’t go to court because it is too expensive. We can’t even get a proper job with that kind of IC, so how to get the savings?” Elisha said.

“No matter how hard it is, I even risked my life to go through the surgery... I am still willing to do so, because I am a girl, and I want to be a girl. I know I will not have regrets and I know what I am doing.

“When I open my eyes, I have to be a woman; if not, I don’t want to wake up,” she said.

Fighting for legal gender recognition

Since that day when the department rejected her application to change her IC gender, Elisha has been forced to continue living with the title of a man.

One day, she drove her nephew to kindergarten, and the police stopped the car and asked her to show her IC. Her nephew was shocked and cried when he heard the police call her “Encik”.

“A few years ago, the immigration (officers) saw my passport. They recognised me as female, but my passport identifies myself as a man. So they took me to a separate room and checked my body, and an officer touched my body.

“I said sorry, do you have any female colleague? They said, ‘So sorry, your passport says you are male, so I have to check’. I feel like as a Malaysian, I don’t have equal rights. It makes some so sad and I do believe a lot of trans people also face the same (issue)”, she said.

A 2017 report published by the Asia-Pacific Transgender Network (APTN) and SEED Foundation on legal gender recognition in Malaysia states that many transgender people are facing difficulties in Malaysia due to their IC gender status.

The report highlights an incident in which a transgender woman in Kuala Lumpur was allegedly asked by police officers stationed at a roadblock for oral sex. Others face barriers when renewing their passports, or have dropped out of university due to strict dress codes that required them to dress in male-normative attire.

Elisha said the incidents stated in the APTN report reflect her lived experiences.

“I do fight for it (legal gender recognition), but it sometimes does not work, not only me for but many of the trans people in Malaysia who also face the same problem. They might be your colleagues, even the auntie sweeping the floor for you…

“And what I did is just (to fight) to return my gender to me.” - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.