When the Multimedia Super Corridor was created in the mid-1990s, during Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s first tenure as prime minister, the rakyat was promised that the internet would not be censored. Thirty years later, it is still largely uncensored, nor is any grand governmental filter like China’s Green Dam firewall put in place.

I was a keen observer of the impact of digital communications technologies on the degree of how nation-states are deconstructed by the power of the technologies that shrink time and space and put distance to death. I wrote a dissertation on this topic, with the birth of Cyberjaya as a case study of hegemony and utopianism in an emerging ‘cybernetic Malaysia’.

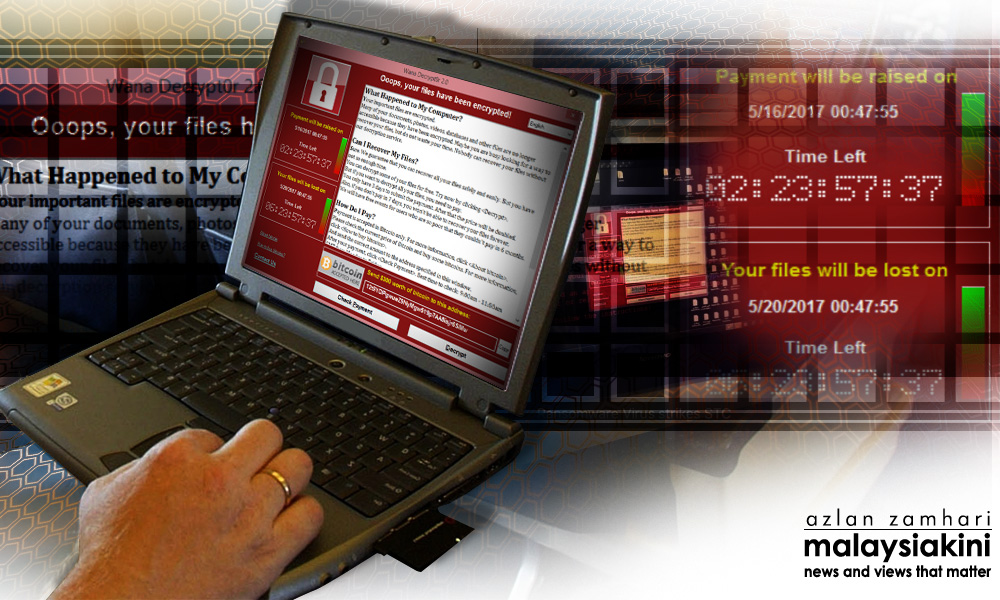

Today, the internet in Malaysia is king, the monarch of misinformation but also messenger of good things, delivered instantaneously. What kind of messiah the internet – the most personalising and democratising tool ever invented – will turn out to be we do not know.

How then is a new government – that promised clean, efficient and trustworthy governance – deal with the inherent contradiction of wanting to allow citizens to tell the truth on the one hand, but refusing to be voted out by the tsunami of critiques on anything, on the other?

In cyberspace, on a daily basis, criticisms are mounted as if a great war is brewing. As if a prelude to the yet another storming of our Bastille. In other words, Pakatan Harapan cannot always hide behind security laws in the age of greater and more massive free speech as practised by its citizens, especially those who voted for change – real, radical change – and not for some new regime that lies through its teeth.

Critical mass

How do we then critique the monarchy, kleptocracy, theology, and ideology – at a time when the powers-that-be seem to be increasingly panicky with the speed by which things are going?

This is a Habermasian question of public space, of “defeudalisation”, and of the way we educate citizen internet vigilantes to exercise free speech in an increasingly authoritarian world.

Consider the scenario the last few weeks. Netizens are getting hauled to the police station for passing comment on the king who abdicated. Not very nice things were said to the monarch.

Pro-monarchy netizens are in an informational war with those angry and dissatisfied with the king who did not tell the country why he went on leave for a few weeks, only to find out later that he was allegedly attending to his own wedding. A racial-antagonistic dimension of this can be discerned.

The Seafield Temple riots in November were made known to the public almost instantaneously with devastating effect, not only on how it got worse, but how the government and the people were trying to deal with the aftermath.

Sadly, a firefighter died and this tragedy is in fact another example of how the internet is a tool of production of both the truth and fake news. In cyberspace, comments take on a troubling racial and religious dimension.

Most of the promises broken by the new regime were leaked at lightning speed, with widespread implications. From the government’s reluctance to recognise the Unified Examination Certificate (UEC), the news of the new car project being public-funded to some degree, members flocking into Bersatu like locusts from Umno and now the Special Affairs Department (Jasa) to the confusing and annoying statements coming from the Education Ministry, the political appointments to GLCs – all these and many more point to the idea that citizens are using the internet to exercise their rights as voters and citizens.

They are speaking up and able to again decide if a new government that can deliver promises better ought to be voted into power in the next election. The internet is king. You can think of more examples of how this technology is a double-edged sword both for the ruler and the ruled. And now we see the Sedition Act 1948 about to be used to compel the rakyat to not speak up.

Those having their voice as internet vigilantes against power abusers continue to play their role. It will take a keen anthropologist to catalogue the thousands of comments that exemplify disgust towards the powers-that-be – produced, reproduced, and made viral – as compared to the few that caught the attention of the authorities.

How to critique

The internet is a virgin forest of information with a life of its own. From it emanates the phenomena of the evolution of truth, multiple truths, alternative truths, and post-truths.

It is a very exciting time for philosophers to study the post-modern thinking activities of the human species. And the internet is the location or space of the battlefields of truths fighting against each other, something those in the US military would call the dromological nature of things, or the speed by which politics moves and removes things, and makes or breaks or multiplies whole truths and half-baked truths.

Is the government looking into this phenomenon? Is it looking into how to educate the rakyat not to say nasty things out of anger and ‘cyber-amok’ conditions – even if what is said is the truth – but to teach them how to say the truth with sound reasoning, using the tools of the critique of power and ideology?

Can the Education Ministry or the Communications and Multimedia Ministry at least provide guidelines on how to critique the monarchy, kleptocracy, ideology, and theology, using sound cultural, philosophical, ideological and liberatory means? This will save netizens from writing things that are true, yet unsubstantiated, and end up in jail.

The government of any day owes the citizens the promise of education for critical consciousness, so that democracy can evolve nicely, and regimes can come and go if it fails to deliver.

It was the internet that helped the new government grab power. It was netizens that helped Harapan win.

Today, the new government must cultivate a new culture of critical consciousness, to teach citizens how to use the Excalibur of the new regime, new excitement, new society. Not for the new emperors to have a newer sword of Damocles hanging over citizens wishing to speak truth to power.

So educate. Teach us how to critique the power abusers be they politicians, theologians, or the monarchs, safely and scientifically.

Wasn’t that the grand promise of Harapan, to leave the idiocracy behind?

AZLY RAHMAN is an educator, academic, international columnist, and author of seven books available here. He grew up in Johor Bahru and holds a doctorate in international education development and Master’s degrees in six areas: education, international affairs, peace studies communication, fiction and non-fiction writing. He is a member of the Kappa Delta Pi International Honor Society in Education. Twitter @azlyrahman. More writings here. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.