By most accounts it has been a hard year for Malaysia politically. After a peaceful election full of hope in May last year, 2019 has brought to the surface the realities of governing a polarized country full of angry mobilized citizens with high expectations and very different visions of the country they want.

Not only have the leaders clashed openly with each other in unstatesmanlike fashion – within the governing coalition and in the newly reconfigured national opposition – but the divisions in society have become heightened fault lines for mobilization of long-standing resentments, especially along ethnic lines.

By year’s end race relations are worryingly worsening and the momentum of building a ‘new’ Malaysia has not just slowed, it has morphed into a baneful sentiment of cynicism and acrimony.

This rancorous spirit of lashing out calls for a serious reflection on developments this year and steps that can move Malaysia forward. There are lessons from 2019 (and in the last decade, outlined in part II) that can serve to strengthen Malaysia, as underneath the sea of negativity lies a reservoir of hope and opportunity waiting to be actualized and empowered.

Broadly, there are four major developments that have occurred in national politics this year.

Leadership weakness

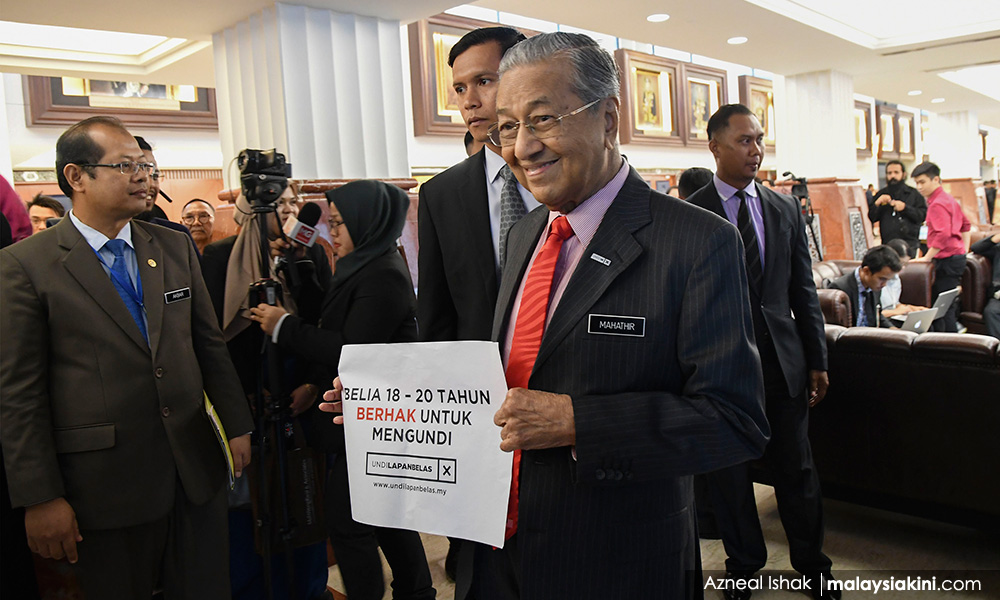

First, and arguably the most evident, has been the failure of national leadership. Full of negativity and sarcasm Dr Mahathir Mohamad has returned to practices of the division and racial politics of the past, and failed to outline a clear direction for the country’s future. At year’s end he has refused to reshuffle his Cabinet and continues to empower ministers who have failed to deliver and served as polarizing lightening rods.

He has moved from a national hero as his popularity has plummeted. He has become the target of anger, especially from many of the voters who put him into office.

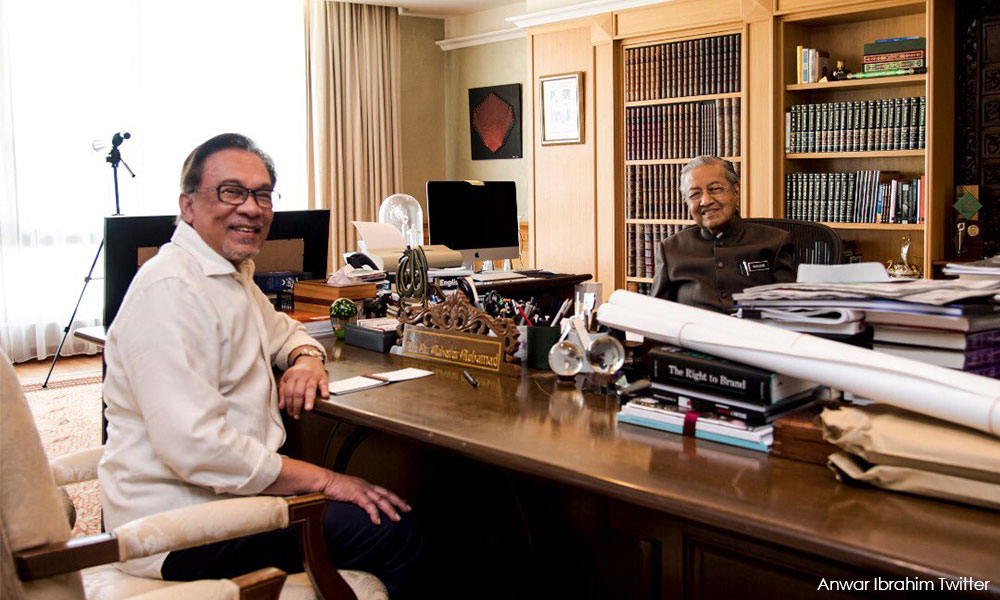

Anwar Ibrahim (above, left), on his part, has been seen to be focused on positioning himself politically rather than working to strengthen the Pakatan Harapan government. This has come as he has engaged in open infighting that has reinforced a public impression of a coalition focused on elite interests as opposed to public welfare. The year has seen a return of the use of sexual scandals and dirty politics to discredit each other.

Younger leaders, who offered hope for Malaysia to move beyond its past, have increasingly opted to leave politics, as the toxic environment has infected the governing coalition itself as well, and fostered distrust among ordinary citizens. Sadly, when Pakatan Harapan politicians speak, increasingly less Malaysians believe them.

Meanwhile, the leaders of the opposition – Najib Razak and Hadi Awang – have similarly shown a lack of acumen to govern Malaysia as a whole. Najib has apparently opted to throw his allies under the bus as he abdicates responsibility for the damage he caused to the country’s reputation and finances in the 1MDB scandal, while the PAS president has opted for an approach that aims to institutionalize exclusionary citizenship and fuel ethnic and religious anger against the nation’s minorities. Neither of these leaders can move Malaysia as a nation forward.

Returned primacy of race and religion

Second, the rise of identity politics is a global phenomenon, but over the year it has taken on greater salience in Malaysian politics with debates over Jawi script, Zakir Naik and the dignity of the Malay community.

Political identity along ethnic lines has long been an integral part of the nation’s fabric, but two catalysts have served to accentuate these in 2019. Foremost is the backlash against the multicultural narrative of GE14, the rejection of demands for more political inclusion of non-Malays and East Malaysians.

Instead of thinking about how Malaysia as a whole can address its challenges in a more competitive global and regional environment, there has been a return to parochial defensive (and offensive) thinking of what different groups should get vis-à-vis each other.

The political vitriol has extended to a ratcheted demonization of parties. The DAP has become the target with a level of anger that echoes the earlier attacks on Umno.

This deepening of identity politics has also been exacerbated by leaders in Harapan buying into the racialized narrative promulgated by the now more unified opposition.

As the opposition now lacks resources and has little to offer in terms of a social and economic programme, given the weaknesses of its leadership and divisions in Umno, the use of race and religion is expedient.

The same excuse cannot be said for Harapan, as many of the coalition leaders similarly are locked in seeing Malaysians one-dimensionally, with a pyramid of rights and roles.

The debates of the year echo those of earlier years over education, affirmative action, religion and race, revealing how pervasive ‘old’ Malaysia is. The fight over rights along ethnic lines has extended into campuses and local communities, as tensions have increased, relationships frayed and trust has eroded.

This combination of backlash and inability to articulate a ‘new’ Malaysia has contributed to the escalation of anger and frustration. It has sucked the hope out of the air, leaving a racialized haze that is choking the country.

Reform shutdown

In the midst of these two issues dominating the headlines, reforms have slowed. Some of these is the product of resistance, sometimes open sabotage by the deep (and shallow) state. Some of these is the realities of being in office – the lack of funds and bureaucratic constraints in adopting new policies.

Most of this, however, goes back to the first point - leadership and a lack of political will. The window for making changes has narrowed and even greater defensiveness and resistance have set in.

Whether this is over police reform, electoral changes, patronage or new (or the removal of old) legislation, the sense is that the Mahathir Harapan government is not willing to deliver on what it was voted in to do, to make changes in the institutions, practices and framework that the majority of Malaysians voted for. All the coalition parties share responsibility for the perceived reform shutdown.

This is not to say that there have not been important reforms in 2019, notably the expansion of suffrage to include younger Malaysians, the strengthening of the judiciary and parliament, the use of the rule of law to address corruption and the delivery of an impressive plan to address graft and abuse, but these developments have been overshadowed by the sense that the political will is no longer there, a sense of defeatism.

Opaque policy direction

Finally, 2019 has not been a year that has witnessed a clear policy direction for Malaysia. The economic numbers compared to other countries remain strong, but these sentiments do not resonate among ordinary citizens who see rising prices and a slow economy.

What is striking at year’s end is how few people can point to positive achievements of Harapan. There have been important programmes developed over the year – Shared Prosperity and Industry 4.0 – substantive policy discussions over poverty and defence, the introduction of measures to improve well-being for the disabled (OKU), and expansion of the social safety net (including higher spending for vulnerable populations), and the introduction of regulations that are in line with international safety standards, e.g. non-smoking and child car seats, but they have not been part of a broader framework that Malaysians can relate to and identify. Many have yet to see their quality of lives improve, and others do not see the improvements tied to government efforts.

This calls for much needed recalibration – a clear prioritization of programmes, better policy coordination, and greater engagement with citizens. Without an effective communication strategy that explains what the government is doing, and its priorities, the focus has understandably been on the promises not met and shortcomings.

Many of these issues have been laid out over the course of the year, as news has concentrated on the negative in 2019. As we turn to 2020, an iconic year for reaching goals for the country as a whole, it is important not be in caught in the negative, to look for, envision and embrace a more positive future for Malaysia.

It is not easy to do this, especially given the realities of the challenges in the nation’s political environment. The year has showcased the serious obstacles ahead. No one said Malaysia’s political transition would be an easy process. Most things worth fighting for are never easy.

BRIDGET WELSH is a Senior Research Associate at the Hu Feng Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies, a Senior Associate Fellow of The Habibie Centre, and a University Fellow of Charles Darwin University. She recently became an Honorary Research Associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia's Asia Research Institute (UNARI) based in Kuala Lumpur. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.