“The social sciences carry stories – of people, phenomena, and philosophies that explain our experiences that shape our world, juxtaposed against data and numbers often exalted and celebrated in the webs of sciences. We tell stories that reveal real people and record their lived life experiences.”

— Paul GnanaSelvam, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (Utar)

In an earlier essay, I looked a bit more into literature and society, but with the current Malaysian situation, rife with political and health crises – and looming ecological collapse – the aim of literature to serve as a mirror to society seemed to feel less urgent.

When I worked in publishing, it was possible to make a case that literature could support the local economy through book sales, royalties for its practitioners, and wages for staff.

But in reality: (1) the local literary ecosystem is tiny, and (2) this reduces literature to pure financial values. As Michael Lapointe reflects in The Walrus - “writing itself should be divorced from financial concerns; but my social instinct recognises this as impossible, and finally undesirable”.

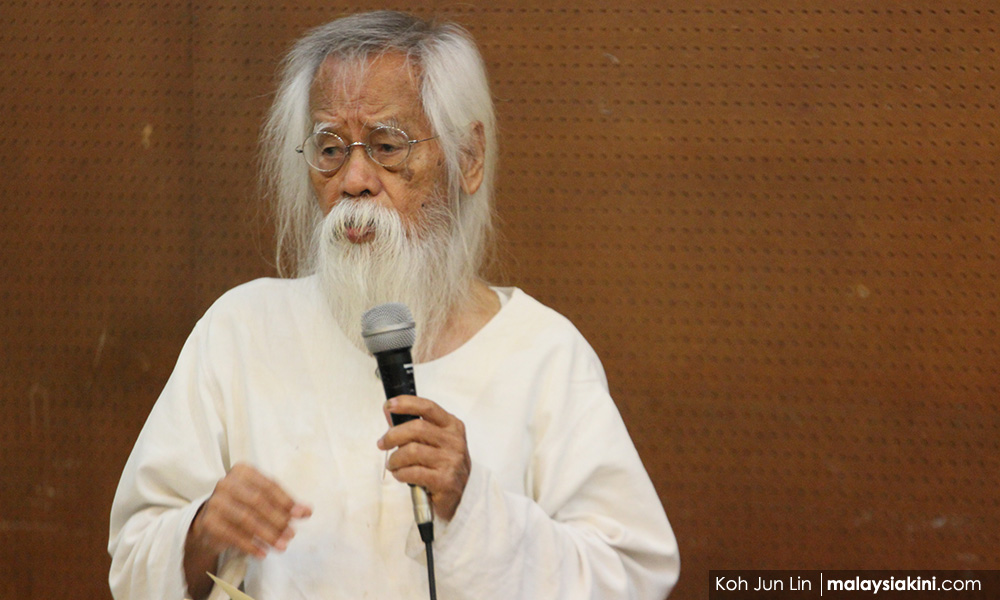

Adjunct Professor Philip TN Koh teaches a course on the intersection of law and literature at the University of Malaya.

I had the opportunity to audit his final class of the semester, which coincided with the commencement of the #Lawan protests in downtown Kuala Lumpur.

The significance of the date was not lost on him or his students, who were young lawyers-in-training.

Literature may not be quite as immediate as acts of political protest, but Professor Koh was cognisant of how literary sentiment cannot be untangled from broader society and the ongoing march of history.

He recalled penning a poem which he declaimed at a conference in Sri Lanka in 1998, allowing for a moment to recognise the human toll of its civil war. Or of reading “Dover Beach” at those white cliffs, reflecting upon war, history, and the passage of time.

Commenting on a student’s sharing of A Samad Said’s poem, “Di Atas Padang Sejarah”:

“Poetry in service of political service can be coopted, and degenerates into polemic. But that doesn’t mean that the emotion is not genuine.

“We are all embedded in history: our personal histories intersecting with the narratives of our nation.

“These intersections will play out in our own lives, the choices we make, what sort of person we will be. Thrown into the padang sejarah.”

A partner at Mah-Kamariyah & Philip Koh, he is a commentator on various legal matters, including constitutional law.

Yet his legal calling allows space for literature, which affords opportunities for greater understanding and empathy, as well as the broadening of one’s worldview, allowing glimpses into characters outside our own immediate spheres in pursuit of our common humanity – or as he puts it, “an exposure of our vulnerability”.

A study of the Graeco-Roman tradition, of Antigone and Euripides, recalls the ideals of the elites of their milieu: “of the idea of freedom, that the monarchs have a place but not at the expense of the nurturing of the spirit of freedom.”

In his capacity as a teacher, his students, with their capacity for analysis and enthusiasm for literature, are a reason for hope in troubled times.

For this reason, he empathically rejects talk of Malaysia as a “failed state”, seeing the promise and potential of his group of students in what he calls “the desert of the pandemic”.

Pursuit of national identity

As Dr Leonard Jeyam of the University of Nottingham Malaysia has also noted, literature does not stand in isolation from politics, especially during periods of rapid transition.

Both fields became inextricably bound when the inculcation of the nation-state was a key priority, as seen through the National Culture Policy of 1971.

Distinctions of “national” and “sectional” literature were explicitly created out of a sense of postcolonial concern, the pursuit of a homogenous identity, defined in turn by language and the medium of expression.

He notes that writers like A Samad Said and Usman Awang would be incorporated into the national canon by default, even if they had no deliberate intention of becoming exemplars.

Yet English-language writing has maintained its vibrancy and potency. “After 1990, literature in English here appears more focussed on the possibilities of being Malaysian more than ever; although in terms of Mahua, Chinese-language literature, I hear that that isn't always the case.”

The different kinds of literature written by Malaysians, both at home and abroad, can traverse wildly different ground. The works of urban noir published by Buku Fixi read differently from those of, for example, Malaysian-Chinese based abroad.

Such diasporic writing may reflect deeply on notions of identity, belonging, or alienation. At times they hint at the artifice of the constructed Malaysia.

Brian Bernards, in Writing the South Seas, brings up the example of Professor Ng Kim Chew who shot to literary fame with his satirical short story, “The Disappearance of M”, where the search for the precise identity of a mysterious writer is elevated into a matter of national importance.

There remain possible middle grounds though, even if the main medium of writing happens to be in English.

Paul GnanaSelvam straddles both the literary world with his recent anthology, The Elephant Trophy and Other Stories, and academia at Utar in Kampar – where he teaches academic writing, research methodology, and communication skills, grappling with the demands of the contemporary university.

He is cognisant of the multiplicity of languages on the ground, even though he started out with a focus on the Tamil diasporic community – in the footsteps of writers such as the late KS Maniam – which means that the language finds its way into his stories.

With time came more opportunities to write about the broader Malaysian cultural landscape, inspired by the “dynamics of experiences, opinions, and events that are constantly unveiling in everyday life.”

The result is a collected cacophony of sounds, voices, and vivid imagery – a boy on the roadside watching a former friend sweeping past in a luxurious car, the everyday frustrations of house-hunting and officialdom, the replacement of kindness and generosity with suspicion and fear.

While the main medium remains in English, “borrowed words from another culture, colloquial or Manglish” find their way in, “to make sure that every reader gets fair access to the content that [he is] presenting.”

Thus the fact that publishers like Fixi do break out beyond language silos offers the opportunity for broadening fresh readership, particularly among the young.

But his creative work seemingly veers sharply from the constraints of academia. In the race for quantification, benchmarking, and excellence, the labour that goes into the creative process – drafting, editing, rejections, and the slog of actually embarking on the publishing journey – remains outside this particular equation.

It may be interesting to bring up some thoughts from the end of the empire – those of the historian Wang Gungwu.

As a young undergraduate at the University of Malaya in Singapore, bred on a diet of Chinese classics and moderns, the traditions of English literature, and emerging regional work, he eventually opted to turn away from a possible career as a poet and/or literary scholar.

Regardless, as he recalls in Home is Where We Are, he credits literature for shaping his emerging worldview, and with it came “a rejection of violence and a preference for measures that promoted freedom… a way of thinking that seemed to be rooted in the literature that the enlightened West stood for (p. 29).”

It allowed for cross-connections beyond Malaya and Singapore, and with the Philippines and Indonesia, for a broader international community awakening to the ideas of rebuilding and reimagining. - Mkini

WILLIAM THAM WAI LIANG is an editor at large for Wasifiri. His new novel, The Last Days, is set in 1981 and covers the continuing legacy of the Emergency. His first book, Kings of Petaling Street, was shortlisted for the Penang Monthly Book Prize in 2017.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.