HISTORY: TOLD AS IT IS | The “official national history” of Malaysia, as portrayed in our school history textbooks, gives prominence to the role played by the moderate United Malays National Organisation (Umno), together with the Malayan Chinese Association (MCA) and the Malayan Indian Congress (MIC), in achieving independence through peaceful means.

However, they downplay the significant role played by the radical Malay-educated intelligentsia (the Malay Left) after the Second World War in championing a more egalitarian Malay society and seeking Malaya’s independence through non-cooperation with the British colonial administration.

Arguably, the radical Malay leaders have virtually become “invisible nationalists” due to the lack of adequate recognition given to their struggle for Malaya’s independence.

Hence, this article seeks to highlight the significant roles and contributions of the key radical Malay nationalists and their political organisations that were in full bloom during the 1945-48 period.

Although largely forgotten today, one is reminded of the due acknowledgement given to radical Malay nationalists in their struggle for Malaya’s independence by none other than the late Dr Ismail Abdul Rahman, former deputy prime minister: “It is true that independence was achieved by the moderate group, but history has also shown that the radical nationalist group also made its contribution towards the achievement of independence.”

It is worth mentioning that the British officials in Malaya during the late 1940s were rather concerned that the influence of radical Malay nationalists was growing at the expense of Umno. Thus, it is not surprising that the British colonial administrators took various measures to suppress the radical Malay nationalists and their political organisations, whilst supporting their main conservative ally, Umno (the Malay Right).

Let’s begin by clarifying what is meant by radical Malay nationalists. According to Gordon P Means, a Western political scientist, radical Malay nationalists were those who “were contemptuous of traditional Malay elites, and wished to pattern Malay nationalism after the Indonesian nationalist movement”.

The radical Malay nationalists viewed the English-educated Malay bureaucratic elite and the traditional aristocratic elite as “colonial puppets” who did not adequately and genuinely champion the aspirations of the Malay masses.

Firdaus Abdullah, in his book ‘Radical Malay Politics: Its Origins and Early Development’, adds further that these radical Malay nationalists were unwilling to cooperate with the British colonial administrators whom they deeply distrusted.

The common aspirations among most of the radical Malay nationalists were to unite the Malays into a dominant force; create a more egalitarian Malay society; enhance the socio-economic status of the Malay masses; seek independence for Malaya and establish a republic through non-cooperation with the British; and to merge Malaya with Indonesia (then the Netherlands East Indies) as part of a wider political union.

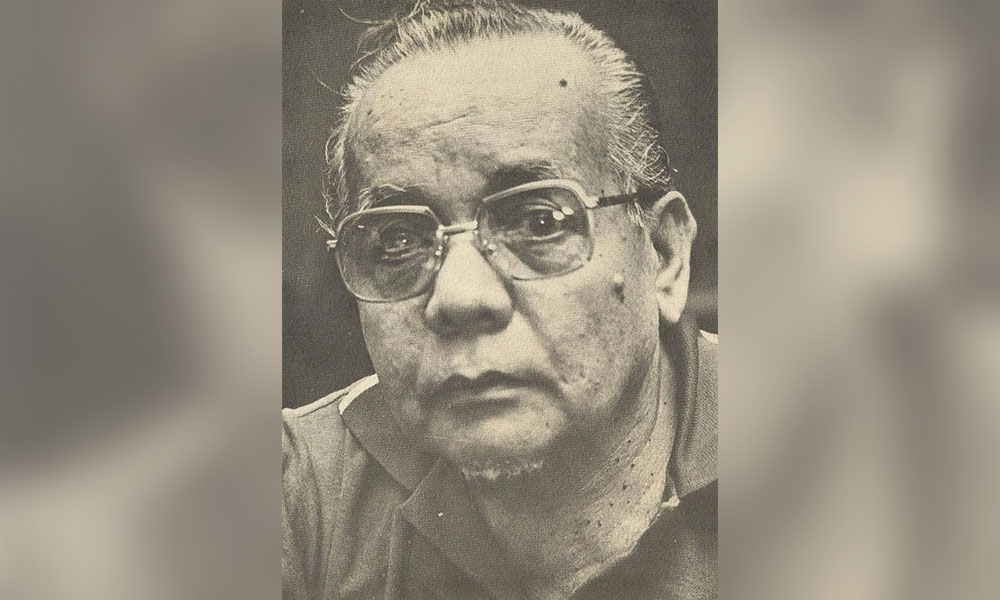

The three most prominent radical Malay nationalists were Ibrahim Yaacob (top photo, left), Ahmad Boestamam (centre) and Dr Burhanuddin Al-Helmy (right). For the record, Tunku Abdul Rahman, our nation’s first prime minister, considered these three radical Malay nationalists as his greatest political rivals.

First Malay left-wing party

Historically, the first Malay left-wing political party was the Kesatuan Melayu Muda (KMM) or Young Malays Union which, according to William Roff, a leading authority on Malay nationalism, was established in 1938.

According to Roff, KMM was vaguely Marxist in ideology and reflected both a strong anti-colonial spirit and opposition to the bourgeois-feudalist leadership of the traditional Malay elite.

KMM fought for the independence of Malaya through non-cooperation with the British and unification with Indonesia in the form of “Indonesia Raya” or “Melayu Raya”. Most of its members were Malay school teachers, staff and students of Sultan Idris Training College, the Kuala Lumpur Technical School and the Serdang Agricultural School, besides journalists.

The main leaders of KMM were Ibrahim Yaacob (founder president), Ahmad Boestaman, Ishak Muhammad, Abdul Karim Rashid, Onan Siraj, Hassan Manan, Isa Mohammad, and Mustapha Hussain.

According to Firdaus, by 1940, KMM had formed branches in Penang, Malacca and in all the nine sultanate states except Perlis. Fearful that the KMM might collaborate with Britain’s enemies, its leaders were arrested in 1940 and imprisoned in Singapore. They remained in detention until released in February 1942.

During the Japanese Occupation of Malaya (1942-45), KMM collaborated secretly with the Malayan Communist Party and the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA) whilst maintaining a cooperative policy with the Japanese.

KMM’s membership reportedly increased from less than 1,000 to about 10,000 during the first two months of the Japanese Occupation. Interestingly, several Malay aristocrats joined the KMM, including Raja Shariman in Perak, Tengku Mohammad Tengku Besar in Negeri Sembilan, Tengku Mohammad Sultan Ahmad in Pahang, and Onn Jaafar in Johor.

As part of the Japanese military policy to discourage political activities by any local group, the Japanese banned KMM in June 1942 and formed Giyu Gun or Pembela Tanah Air (Peta) with the assistance of KMM’s leaders. Peta was a military organisation under the leadership of Ibrahim Yaacob.

In July 1945, the Japanese encouraged Ibrahim Yaacob to establish Kekuatan Rakyat Istimewa (subsequently known as Kesatuan Rakyat Indonesia Semenanjung, or Kris). Its establishment was a preparatory step towards Malaya’s independence as Japan had foreseen its defeat in the Second World War at this point in time.

Kris’ activities came to a halt when Japan surrendered in August 1945. Ibrahim and several KMM leaders then fled to Indonesia. The remaining KMM’s leaders in Malaya were imprisoned by the British Military Administration. Ibrahim eventually died in Jakarta on March 8, 1979.

Meanwhile, Ahmad Boestamam established Angkatan Pemuda Insaf (API) in February 1946 which sought the independence of Malaya, by force if necessary. API provided paramilitary training for its members who adorned special uniforms and sang patriotic marching songs.

Ahmad Boestamam published a 26-page booklet, ‘Testament Politik API’, with its clarion call, ‘Merdeka with Blood’.

API advocated a classless society and a state-controlled economy. API’s influence spread quickly and its membership increased from 2,560 at the end of 1946 to about a sizeable 10,000 in mid-1947. Due to its radical nature and burgeoning influence, API was banned by the British on July 17, 1947. Ahmad Boestamam was subsequently detained by the British from 1948 till 1955.

Creation of a republic

KMM’s successor was the Partai Kebangsaan Melayu Malaya (Malay Nationalist Party, or MNP) which was established by Mokhtaruddin Lasso (one of MPAJA’s leaders) and Ahmad Boestamam on Oct 17, 1945, in Ipoh, Perak. The party’s leadership soon passed to Dr Burhanuddin, Ahmad Boestaman and Ishak Muhammad.

As of the end of 1947, the MNP had a recorded membership of 53,380 with Perak as its stronghold. MNP’s two main aims were attaining immediate independence for Malaya through a merger with Indonesia and economic upliftment of the Malay community whilst maintaining friendly relations with other ethnic groups. The MNP promoted the creation of a republic in Malaya.

Subsequently, the Malay radical parties formed Pusat Tenaga Rakyat (Putera) on Feb 22, 1947, to oppose the new constitutional proposals by the Working Committee which was established by the British (comprising six British officials, four representatives of the Malay rulers and two representatives of Umno) to replace the unpopular Malayan Union which came into being in April 1946.

Putera consisted of several organisations, the main being the MNP, API and MNP’s women’s wing, Angkatan Wanita Sedar (Awas) led by Shamsiah Fakeh. Among the principles championed by Putera were a united Malaya, including Singapore; a popularly elected federal legislative assembly and popularly elected state councils; Malay to be the official language; and provision of special political and economic privileges for the Malays.

Putera joined forces with the All-Malaya Council of Joint Action (AMCJA) - consisting of several non-Malay organisations under the chairmanship of Tan Cheng Lock - to oppose the Federation of Malaya plan by the Working Committee.

Putera-AMCJA formulated the People’s Constitutional Proposals (People’s Constitution) as the basis for Malaya’s independence. These proposals were as nationalistic as they were bold and visionary in their attempt to bring together the various ethnic groups in the country.

Asserting Malaya as a multiracial country, the proposals called for a popularly elected federal legislature and state councils, a citizenship policy granting equal rights to all residents who owed loyalty and allegiance to Malaya, and Malay to be the official language.

The Straits Times (Sept 23, 1947) acknowledged the importance of the People’s Constitution by describing it as “the first attempt to put Malayan party politics on a higher plane than that of rival racial interests, and also as the first attempt to build a political bridge between the domiciled non–Malay communities and the Malay race.”

In protest against the competing Federation of Malaya plan by the Working Committee, Putera-AMCJA organised a one-day nationwide hartal on Oct 20, 1947, which had massive public support. However, the People’s Constitution, as expected, was rejected by the British colonial administration in favour of the Federation of Malaya plan.

Coming back to the MNP, the party dissolved itself in May 1950 because it did not want to formally register under the new society ordinance imposed by the British colonial government. Upon his release from imprisonment, Ahmad Boestaman formed Partai Rakyat Malaya (People’s Party of Malaya) on Nov 11, 1955, and was subsequently elected to the House of Representatives in 1959 as a Socialist Front member after winning the Setapak parliamentary seat.

As for Dr Burhanuddin Al-Helmy, he was subsequently elected president of the Pan-Malayan Islamic Party (PMIP) in December 1956. The PMIP would eventually evolve to become known as PAS that we know of presently.

Major contributions

Let’s now consider the major contributions of Malay radical nationalists towards the achievement of Malaya’s independence and nation-building.

First, the Malay radical nationalists helped to foster Malay political consciousness and the need to unite and protect their interests vis-à-vis, other ethnic groups, through their exhortatory articles in the Malay press.

Second, they helped in shifting Malay political consciousness from the state level (semangat kenegerian) to the national level (semangat kebangsaan). They exhorted the Malays to view themselves only as “Orang Melayu”, and not to segregate themselves provincially as “Orang Johor” or “Orang Perak”, or ethnically as “Orang Jawa”, “Orang Bugis” or “Orang Minangkabau”.

Third, Umno emulated API’s strategies of mobilising Malay youth such as flag flying, wearing of uniforms and marching.

Fourth and finally, a little-known fact is that several youths of API subsequently held important public positions in independent Malaya. Among them were two cabinet ministers, Umno stalwart Abdul Ghafar Baba and PAS leader Mohd Asri Muda, and Abdullah Ayub who served as the sixth chief secretary to the government in 1979-80. Additionally, Aishah Ghani, the first president of Awas who later joined Umno, served as the minister of social welfare from 1973 until 1984.

In a nutshell, the radical Malay nationalists too were patriots like those from the more moderate political organisations. They put up a dedicated, valiant and protracted struggle to seek Malaya’s independence and to promote a more egalitarian society - with some of them suffering personal hardships in the process.

Our school history textbooks should adequately highlight their contributions towards the achievement of Malaya’s independence and not relegate them to become “invisible nationalists”. - Mkini

RANJIT SINGH MALHI is an independent historian who has written 19 books on Malaysian, Asian and world history. He is highly committed to writing an inclusive and truthful history of Malaysia based upon authoritative sources.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.