HISTORY: TOLD AS IT IS | It is a little-known fact, as reported in The Straits Times (March 26, 1889), that since the 1880s, men of the First Battalion Perak Sikhs, through the employment of agents, were lending money at heavy interest to the Chinese without official sanction.

By the early decades of the 20th century, thousands of Sikhs, particularly from the class of watchmen and ex-policemen, were involved in moneylending. Any account of Sikh moneylenders in Malaysia cannot but include Jagat Singh of Perlis, who was reputed to be the wealthiest Sikh businessman of his time in Malaya, owning rubber estates, tin mines and landed property.

Writing about Sikh watchmen and moneylending, The Straits Times (June 30, 1935) stated: “It is well-known that many a Sikh jaga (watchman), employed to guard buildings and property, is much more concerned with his little moneylending ‘sideline’ which produced a profitable income from the interest on debts alone.”

Their place of work functioned as the “office”. Interesting and amusing as it may seem, it was not uncommon for the manager of the very bank that a Sikh watchman was hired to guard, to be a client of his watchman-moneylender! One instance was a Chinese bank manager of OCBC Segamat in Johor who borrowed money from Pall Singh, the bank’s watchman.

Sikh moneylenders generally provided loans in small sums, normally a few hundred dollars. Most of their clients were clerks, labourers, artisans and small shopkeepers. In particular, indebtedness was widespread among the Malayan clerical community.

The Sikh moneylenders generally charged interest rates ranging between 24 and 36 percent a year. It does appear that an interest rate of 36 percent per annum was an acceptable practice as Raja Bilah, Penghulu of Papan in Perak, took a loan of $900 at such a rate from a Chinese, Leong Ah Chong, for two years. This transaction was witnessed by JBM Leech, the Collector and Magistrate of Papan.

It was not unusual for Sikh moneylenders to sign the loan documents in Punjabi or simply by crossing an “X”. For names of Sikh moneylenders in loan documents rendered in the Jawi language used by Malays, as stated by Abdur-Razzaq Lubis and Khoo Salma Nasution in their book, ‘Raja Bilah and the Mandailings in Perak, 1875-1911’, “bin” was used to denote “son of”, as for example, Sundar Singh bin Matab Singh and Manggal Singh bin Sundar Singh.

Undoubtedly, Sikh moneylenders contributed to the development of the retail trade in Malaysia by providing start-up capital to family businesses and short-term loans to shopkeepers.

Indeed, the positive contribution of Sikh moneylenders to the growth of the nation’s economy was acknowledged by Sir Cecil Clementi Smith, High Commissioner for the Malay States, when making reference to Jagat Singh’s extensive moneylending activities in Perlis: “Much might be written in condemnation of the Indian moneylender, though it must be recognised that he may, and not infrequently does, fulfil a useful part in the development of a young country.”

Great Malayan ‘banker’

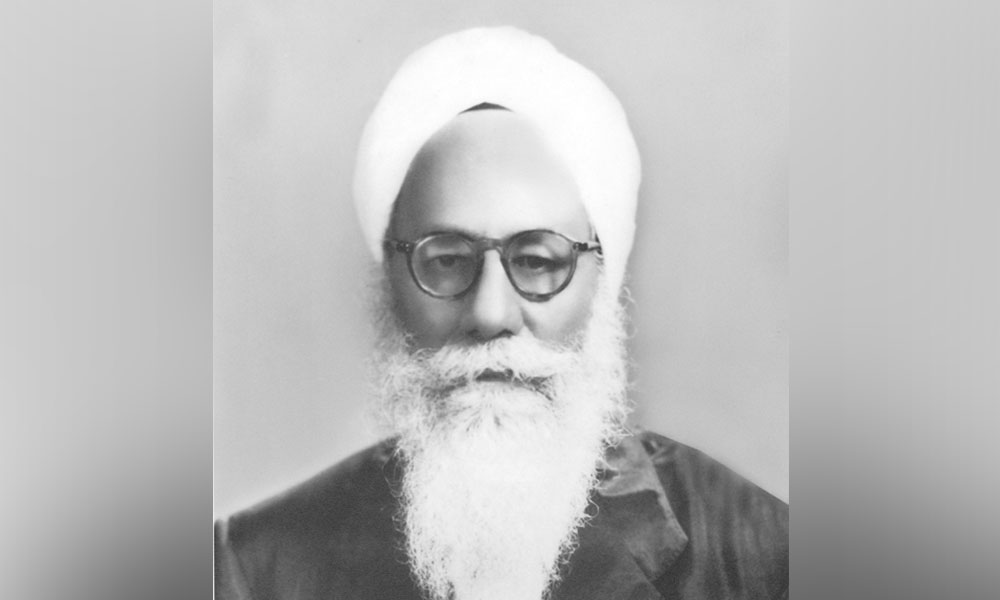

Jagat Singh, the great Malayan “banker”, was born in Mehlowal village, Sialkot district, Punjab in 1881. He was employed as a compounder or dresser in the 34th Sikhs (British Indian Army) for five years. He resigned in 1905, proceeded to Perlis in 1906, and gained employment as a dresser in Kangar government hospital.

Jagat Singh was also placed in charge of the prison and was thus for all intents and purposes, the “state engineer” as all public works were then performed by prison labour. He practically ran the public works, prison and medical departments in Perlis.

By 1915, Jagat Singh as reported in British records, had also “established a fairly extensive moneylending business, the Raja of Perlis amongst others, being found to be in his debt to a very considerable extent.”

The British government was extremely concerned about Jagat Singh’s growing influence among the ruling court in Perlis, as expressed by Philip Cunliffe–Lister, Secretary of State for the Colonies: “He was acquiring in addition to wealth and real estate a position of control over the leading powers of the State which enabled him to dispense patronage and which might, but for the presence of the British Adviser, have developed into a position where the great ‘banker’ also decided policy – the Perlis Rothschild. This would have been especially undesirable in view of his doubtful attitude during the War.” Jagat Singh has been described as a “well-known seditionist” in British records.

It was widely believed that Jagat Singh would own half of the land in Perlis due to huge debts owed to him by the ruler of Perlis, Raja Syed Alwi Jamalullail, if he was not banished from the state. The debts owed to Jagat Singh by debtors of all classes totalled $830,000, out of which no less than $117,142.16 was owed by members of the royal family, state council and government officers.

Tuan Syed Hamzah, Vice-President of the State Council, owed Jagat Singh $24,000 and no repayment was made for several years. Nearly one in every 200 of Perlis’ population were Jagat Singh’s judgement debtors. Incidentally, the members of the “Kerabat” (Ruling House) are immune from being sued in any court of law. Jagat Singh, according to British records, was also the “owner of extensive house property, building land, tin mines, rubber estates and padi lands, which ... have come into his hands as the result of foreclosures.”

Eventually, the Perlis State Council approved Jagat Singh’s banishment for life from the state in its meeting of Nov 5, 1931. Jagat Singh departed Perlis for Penang on the same day. It was feared among British officialdom that Jagat Singh had “obtained a stranglehold over the public service” in Perlis, which was “nothing less than paralysing to good government.”

The British authorities were also concerned that Jagat Singh’s “continued presence in the State was a menace to good government and the prosperity of the State.” It was also feared that the courts had become “the private debt-collecting agency” for Jagat Singh. The courts “were not only failing to give debtors the relief to which they were under the Moneylenders Enactment entitled, but were passing decrees for amounts far in excess of what could legally be claimed and in some cases for amounts which were not even due.”

Jagat Singh died in Penang on Dec 26, 1956. His funeral, as reported in the Straits Echo and Times of Malaya (Dec 27, 1956), “was very largely attended, the procession being one-mile long.”

Moneylenders association

To safeguard their interests, the Sikh moneylenders established the Punjabi Sahukara (Moneylenders) Association Malaya (PSAM) on Aug 11, 1951, in Kuala Lumpur. About 90 people attended the inaugural meeting.

The founder president was Jang Singh of Klang, whilst the secretary was Inder Singh, and the treasurer was Kishan Singh, both from Sentul, Kuala Lumpur. Membership was open to every Punjabi carrying out moneylending business within the Malayan peninsula. In 1975, there were 321 Sikh licensed moneylenders in Peninsular Malaysia.

Under the Moneylenders Act 1951, the interest for a secured loan shall not exceed 12 percent per annum and the interest for an unsecured loan should not exceed 18 percent per annum.

It cannot be denied that there are black sheep in any profession and there were known cases of unlicensed Sikh moneylenders charging exorbitant interest rates and getting clients to sign blank promissory notes with the amount of the loan left out. At the same time, of course, there were also dishonest borrowers who had no scruples about evading their debts.

PSAM, through the initiative of Palwinder Singh Khosa, Parpur Singh Gill, Ba Beanat Singh Dhaliwal, and Amritpall Singh, a lawyer, was rebranded in 2012 and registered as the Malaysian Punjabi Licensed Moneylenders Association (MPLMA).

Currently, it has about 700 members, of whom more than half are non-Punjabis as associate members. MPLMA has organised numerous seminars to enlighten its members regarding proper documentation and adherence to the Moneylenders Act 1951. - Mkini

RANJIT SINGH MALHI is an independent historian who has written 19 books on Malaysian, Asian and world history. He is highly committed to writing an inclusive and truthful history of Malaysia based upon authoritative sources.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.