Mohd Ariff Sabri Aziz, FMT

We have learnt a few things in the last few weeks. The governments in Tunisia and Egypt fell. There were no sudden eruptions of violent overthrow.

The two leaders who governed the two countries ruled firmly; they had control over the suppressive resources of the military and the police and they gave their people development.

The leaders were all rich people and had plenty of money.

But in the end, money and wealth were no longer considered important determinants and were not able to contain years of frustrations, anger and pent-up disillusionment among the masses.

Small and sometimes imperceptible changes here and there were not taken seriously by the leadership.

Small and sometimes imperceptible changes here and there were not taken seriously by the leadership.

That is until things reach a tipping point. In Tunisia, the tipping point was when a petty trader set himself ablaze.

Perhaps Gary S Becker, a Nobel prize-winning economist, summed it best when he wrote:

“Analytically, what happens is that over time such a regime may be shifting in unnoticed ways from stable equilibrium positions, where the government is in complete control, to an unstable equilibrium where seemingly small events trigger massive changes, including the ouster of the government.

“The overthrow of the government may be quick and without much violence, as in the East German and Tunisian cases, or involve considerable violence, as during and especially after, the Iranian revolution.”

Festering fear

Another equally reputed economist, Richard Posner, noted that there were several reasons for an “overthrow.”

“The obvious one is lack of information. A government that uses intimidation, surveillance, and control of media to quell dissent deprives itself of good information about the population’s concerns.

“People keep their concerns to themselves out of fear. Grievances are driven underground, to fester.

“Not having a good handle on what people want, the government risks being blindsided by a sudden explosion of repressed anger.

“Repression also fosters conspiracy; fearful of expressing themselves publicly, people learn to form secret cabals; they become experts at dissimulation.

“Second, the leadership of an authoritarian regime has difficulty obtaining information even from its own officials, or more broadly of managing disagreement and absorbing and responding to criticism.

“Without fixed terms of office and rules of succession, the position of leaders is insecure: they maintain their position by charisma or fear, by projecting an image of infallibility and omniscience, and these sources of power are undermined by criticism, which is often implicit in ‘bad news’ conveyed to leaders by their subordinates.

“Even without being critical, the subordinate who warns his leader about popular disaffection is implicitly claiming to have knowledge that the leader did not have.

“Third, and again attributable to the absence of set rules for peaceful transition of leaders, authoritarian regimes tend to be conservative in the sense of being reluctant to change even in response to known problems.

“If you do not have a good handle on public opinion, it is very difficult to predict the consequences of change – change may convey weakness, create expectations that cannot be fulfilled, empower the advocates of change, and undermine belief in the infallibility and omniscience of the leadership.

“Fourth, and again related to the absence of regular rules of appointment and succession, the leadership of authoritarian regimes tends to be old and sclerotic. Retirement is dangerous. The leader will have made enemies and when he relinquishes power he is defenceless against them.”

“By clinging to power he grows out of touch, and is ill-equipped to respond decisively and effectively to a challenge.”

People must decide

The things that happened in Tunisia and Egypt belonged to the realm of chaos theory.

A simple analogy of this theory is like when we rock a canoe. The canoe contains the momentum of disequilibrium until we rock it once more and the canoe overturns.

The initial conditions or the initial stimuli seemed at first remote and insignificant but over a period generates widespread effects.

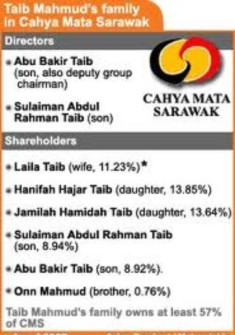

In the case of Sarawak, we don’t know which will generate “an effect”. It could be the (online) articles about (Chief Miinister) Taib Mahmud’s personal fabulous wealth.

Or maybe even articles of his family’s decadent and opulent lifestyle amplified with unbounded pomposity which appeared in lifestyle magazines like Tattler, Passion.

Or maybe it will be his business deals with a set of cronies.

On the whole, although these are taken dismissively, I am sure one of them will precipitate his downfall.

There’s one thing that Sarawakaians in general must realise.

When it was ruled by the Brooke family, Sarawak was actually run by a private limited company.

Except for a brief period, when Sarawak was ruled and governed by some fragments of democratic institutions directly elected by the public, Sarawak is essentially now back under the rule of a limited company.

Except the company is now owned by a native of the soil – a Melanau by the name of Taib Mahmud.

Sarawak is run like a personal fiefdom where the “king” dispenses with largesse to whosoever he has taken a fancy and who he thinks fit into his strategic interests.

Sarawakians need to ask this question – do they still want to be ruled by a sendirian berhad or empower themselves by electing a democratic government?

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.