We finally have a date for the swearing-in of the rest of the cabinet members – July 2. Why such a long delay, especially when the list was reportedly sent to the Yang di-Pertuan Agong on June 20, remains unclear.

We experienced similar delays in the appointment of the menteri besar of Perlis and Selangor, and to a lesser extent, in the appointment of the prime minister after GE 14. Before this, there was also the Selangor political crisis of 2014.

All these incidents speak of political instability that results from a failure of the system to work in the manner that it should.

Institutions and processes of government should be codified in such a manner as to hold true to democratic principles, uphold constitutional monarchy and efficiently provide for all numbers of scenarios.

Having proper laws and processes in place ensures that every institution involved will execute its duties as envisaged in the Federal Constitution, while giving minimum (if any) leeway for what could broadly be termed as human error.

I am neither a lawyer nor a constitutional expert but perhaps, even as laymen, we can sketch out some of the principles that would inform a more formal, structured and resilient codification of the process of appointing a head of government.

In order to achieve this goal, a number of institutions must perform their duties correctly.

Chronologically, the first in this process is the Election Commission, which must tally and report the results of an election accurately and impartially. Pages upon pages could be written on this alone, but to move forward, for now, let us assume that this is done.

Thereafter, there should be an accurate list of all the elected representatives. If no party or coalition is able to form a simple majority, then there is another set of contingencies, again mostly beyond the scope of today’s article.

If there is a clear simple majority, however, which has unanimously agreed on a candidate for head of government, then from this point forward there should not be any ambiguity or excessive amounts of discretion.

The current wording of the law, which has variations of requiring a monarch to appoint an individual he believes commands the majority of support in the legislative is overly vague, and likely gives too much personal latitude.

What we need is a clearly outlined, step by step, black-and-white process, for the newly elected legislators to indicate their choice of head of government.

An example might be a specific document - formally standardised, legally recognised and carrying legal weight - that must be signed and verified via a public, transparent process to indicate the new ruling party or coalition’s single choice for head of government (as the practice of providing a list of many names for the monarch to choose from is also likely not in keeping with the principles of a democratic constitutional monarchy).

Once this document has been verifiably produced, the constitutional monarch should be given little or no discretion in appointing this individual as head of government.

Conditions for justifiable rejection

This is not intended in any way to reduce the monarch’s role to a rubber stamp. There are still scenarios we can envision wherein the monarch - in executing his role as an institution of check and balance - might justifiably refuse to swear in an individual as head of government.

In theory, though, these scenarios should be extremely limited, and subject to a transparent, formally codified set of criteria. In essence, a monarch should not be able to refuse swearing-in an individual merely because he does not like the said individual, for instance.

This would provide the monarch powers that are clearly not envisaged in the concept of a democratic constitutional monarchy, and have elements instead of an absolute monarchy - a system rightfully almost extinct in the modern world.

However, we can codify a set of instances in which a monarch can legally and justifiably refuse to swear in an individual as head of government.

For instance, a set of conditions can be imposed for any incoming head of government. Failure to meet any of these conditions can then be used by the monarch as a transparent justification for refusing to swear in an individual who fails to meet those conditions.

Some examples of conditions under which a constitutional monarch might justifiably reject a candidate: concrete, proven evidence of corruption; openly demonstrated and/or expressed contempt for or intentions to compromise institutions such as the judiciary or other institutions of check and balance and so on.

These are merely examples. Ultimately, Parliament - as the nation’s legislative body - will have to decide exactly what the criteria for a head of government is to be, and under what conditions a monarch can reject a candidate.

The duty of determining whether or not any charges that a candidate fails to meet the aforementioned criteria are true should be left to other institutions, like the courts and the police - not to the monarchy (as that would lead us back to square one).

There should also be a codified limit as to the amount of time a monarch can delay an appointment. This should allow for any proper investigation regarding the candidate, but not be so long as to cause excessive instability.

Ultimately, what matters is that a constitutional monarch’s discretion is limited to specific, clearly spelled out criteria under which he can justifiably and transparently refuse to swear an individual in.

In all other circumstances, as long as the process from election through to the naming of a properly elected legislative choice for head of government is properly adhered to, a monarch should be legally compelled to accept this choice.

A similar process and set of criteria should also apply for the naming of the exco and cabinet line-ups.

More democratically accurate

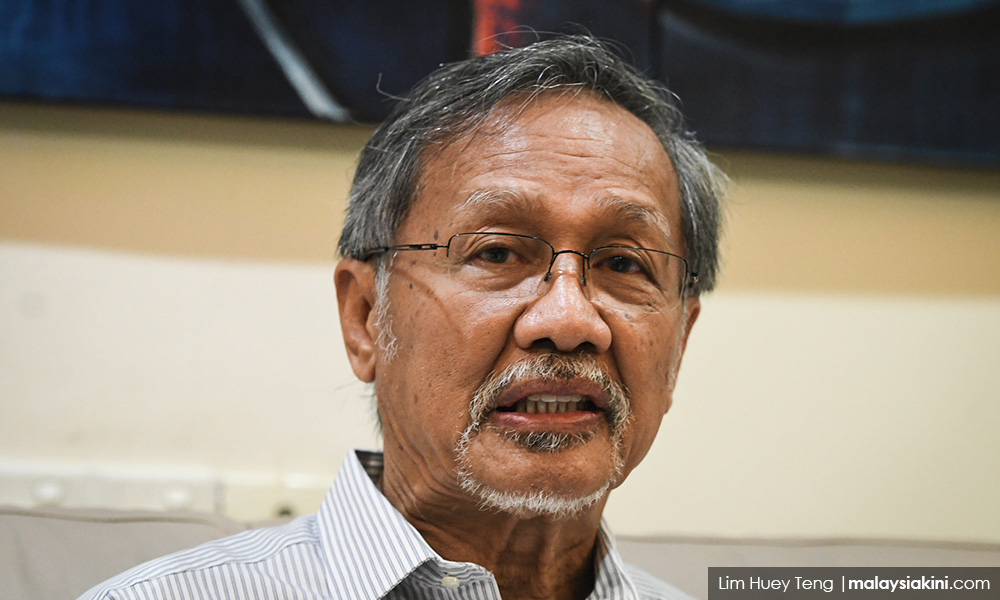

Had a system like this been implemented, we would have most likely seen Ismail Kassim as menteri besar in Perlis, Dr Wan Azizah Wan Ismail as menteri besar in Selangor in 2014, and - only if you believe his version of the story of course - Idris Ahmad (photo) as menteri besar of Selangor in 2018.

The point, of course, is not whether we get our preferred candidate elected as head of government.

The point is for there to be a codified, consistent, transparent and democratically justifiable system in place to reduce undue errors within the process on the part of an individual or institution.

It cannot be said that such a system guarantees that we get the “best” possible candidate; the goal of such a system, however, is instead to get the most democratically accurate candidate.

In a number of ways this also protects the royal institutions from being besmirched by political involvement.

We have seen instances of such inappropriate political involvement on the part of the royalty, especially in the run up to the 14th general election (GE14).

Having read them closely, I agree that writings of individuals like A Kadir Jasin may have been a little too aggressive in their attempts to call out such political activism.

It is probably unwise for efforts to do so to be coloured with resentment stirring or angry incitement.

That said, it is true that members of the public should speak up (in as dignified and civilised manner as possible) if any element of government, including the royalty, are not executing their duties in proper adherence to the spirit - and/or better yet, an improved letter - of the Federal Constitution.

With better worded, less ambiguous laws and processes in place, everyone is likely to do their job better, and respect for government institutions all around is likely to increase.

Our monarchies have good potential to play a significant and meaningful role in the governance of the country we all love. Let us empower them to do exactly that.

NATHANIEL TAN is eager to serve. -Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.