In Malaysiakini’s conversations with victims and eyewitnesses of the May 13, 1969 riots, many struggled to gather their thoughts when recounting their experiences.

They often broke down during interviews and some admitted having never spoken about what happened, until now.

One 70-year-old man said he had never told his family how he had offered himself to be killed in order to save a young Chinese family from a Malay mob, during the riots.

He was in tears as he recalled how he tore off his clothes during the episode of hysteria.

Fifty years on, he has not been able to understand why he reacted that way that day and continues to have flashbacks of the incident when he is near where it happened.

In another interview, a woman - also in her seventies - paused several times to regain her composure as she recalled the day she learned that her grandmother, mother, and siblings aged 18, 14 and 10 had died during the riots.

She survived because she was not in Kuala Lumpur on that day and upon returning, she found her brother's dismembered remains in what was left of her family home after it was razed to the ground.

“All these years, I have not dared to think about it, or talk about it, or even ask about it.

“Because the thought of them just hurts too much,” she said.

Like the man, she has been unsuccessful at burying this memory, but also confessed to being afraid of forgetting her loved ones in case no one was around to remember them anymore.

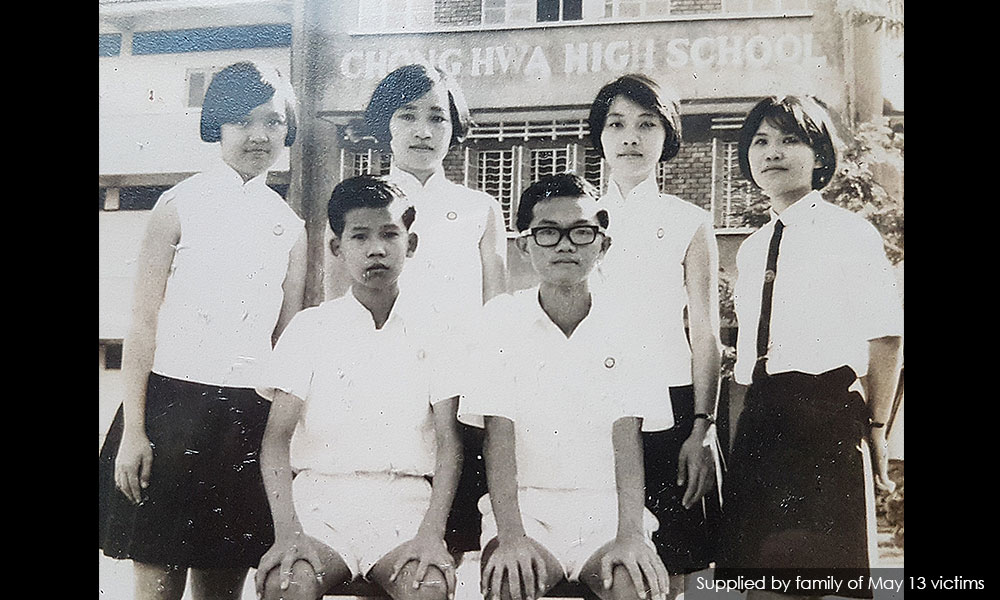

She carefully preserves keepsakes recovered from the family home -- school exercise books belonging to her brothers and their childhood drawings, her grandmother’s clothes and her mother’s broken glasses -- as evidence of their lives.

She has never discussed May 13 with her surviving siblings, and whenever the topic was brought up in conversations, she would have trouble sleeping and even feel suicidal as a result.

Half a century has passed and there is no longer a tangible threat to their safety, but perhaps a sign of their prolonged trauma, both wanted to remain anonymous.

Secrecy is the site of dysfunction

Not talking about past trauma can cause victims to relive their distressing experiences as they have not been able to make sense of what happened, said clinical psychologist K Vizla when asked about these accounts.

“Trying to forget a memory like that is futile. Unfortunately, this is what many people try to do, and it actually causes more psychological harm. Forgetting is not a good coping mechanism,” she said.

As such, Vizla believed it is important for the government to encourage discussions around May 13 to break the silence that has engulfed it.

“There is so much secrecy around the May 13 incident. Secrecy is the site of dysfunction.

“The longer there is silence around the issue, the harder it will be for survivors to heal from their trauma,” she said.

Such conversations would benefit not just the survivors but also their family members, who often live with second-hand trauma that they inherited.

“The trauma now extends to a few generations. All of us need to collectively heal,” Vizla said.

Trauma and radicalisation

Trauma could also manifest in different ways.

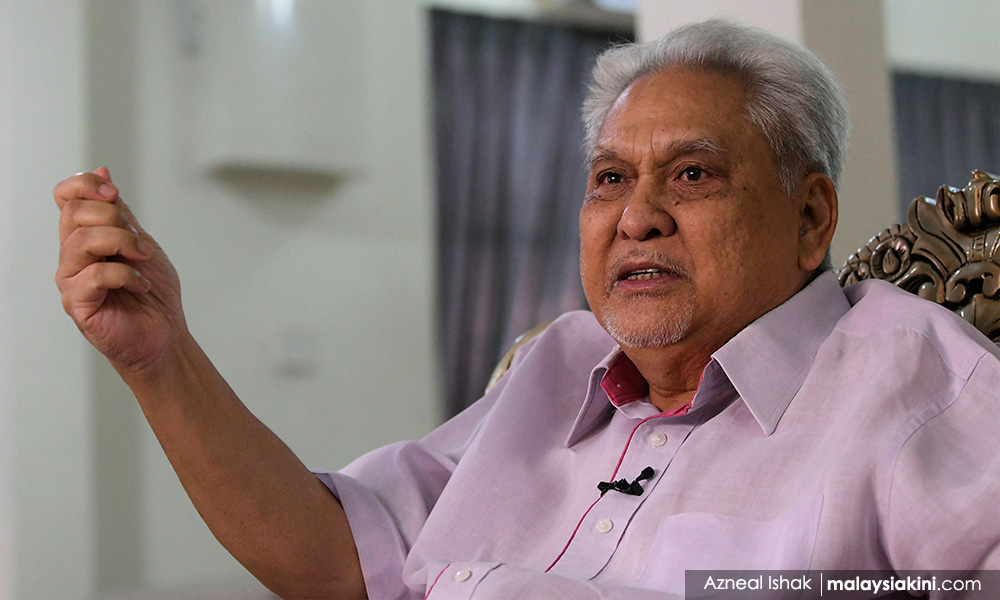

Abdul Rahman Mohd Noor was a 21-year-old student living in Kampung Baru, a riot hotspot and witnessed mobs attack unsuspecting bystanders.

Growing up in a multi-ethnic setting, he had many childhood friends from other races and had harboured no suspicion against non-Malays.

“But May 13 made me and (Malay) friends my age very angry. It ignited a strong feeling of ‘Malay-ness’ within us.

“After two to three years, I became someone hot-tempered. And if there was any mention of Malay rights or interests, I would say, ‘No compromise!’,” he said.

Without an avenue to unpack the distrust he had developed; it would be many years more until Abdul Rahman managed to overcome those feelings.

“After a while, I came to realise that you can’t clap with one hand,” he said.

SH: Weaponised discourse

SH: Weaponised discourse

The academic Por Heong Hong, who has written extensively about May 13, called for more safe spaces that would allow people to talk about what they went through.

In her interviews with victims and their families, she found that many continued to be haunted by their memories and feared the possibility of recurring violence because they had not been able to discuss their experiences.

The independent researcher opined this culture of silence was partly driven by how the discourse on May 13 has thus far been hijacked, and weaponised, by politicians.

“May 13 itself as an incident has been made into a symbol to threaten people by certain politicians. Like if you vote for a certain party or certain members of the society, you are going to create a lot of trouble.

“It has been made into a symbol of violence, and no one is allowed to tell a narrative that is different from the official one,” Por said.

The lack of safe spaces and the subsequent vacuum of personal accounts has ultimately deprived the public, especially younger Malaysians, of a deeper understanding of May 13 and why it should never happen again.

This was made worse by the lack of detailed information on the 1969 riots in the National Archives or national libraries.

Photos, books, and newspaper clippings on the incident only started entering the National Archive’s collections in the early 2000s.

The incident remains absent from the national school history syllabus, despite its lasting impact on Malaysian history and current policy-making.

Losing the human stories

The stigmatisation of the event has also placed a veil over the human stories of May 13 - many eyewitnesses, survivors, and loved ones of those who perished still dare not share their stories.

“It is these human stories that are missing from all the narratives about May 13. The human experiences and the human faces of the incident.

“Who were those people? What happened to them after the incident?” Por questioned.

With many witnesses now advancing in age, the window of opportunity to record this oral history is narrowing.

For some, like Abdul Rahman, the passage of time has prompted a sense of urgency to share their experience, especially with young Malaysians.

The 70-year-old eyewitness who spoke under condition of anonymity said he felt compelled to tell his story now, because he heard younger Malaysians threatening “another May 13”.

“People like us don't want to talk about it. We'd rather keep quiet and hope it will never happen again.

“The only reason I am talking about it now is that I think it’s time. Many of us who witnessed it have died.

“The only reason I am talking about it now is that I think it’s time. Many of us who witnessed it have died.

“I want this story to be a lesson. My fervent wish is that it will never happen again,” he said. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.