After three years of relatively clear skies, the haze reappeared in Malaysia in 2019. One of the worst-hit areas this year was Sri Aman in Sarawak, which recorded its highest Air Pollution Index (API) at 369 – well into the “hazardous” range.

While an early monsoon transition brings welcome respite to most areas of Malaysia, fires rage on in neighbouring Indonesia, turning the skies blood red.

Haze is generally linked to Indonesian forest fires and, to a lesser extent, in Malaysia as well. Such fires occur in the dry season on almost a yearly basis.

For most years, the haze is confined locally and it is communities living closest to the fires that must contend with these dangerous conditions. But every few years, a combination of atmospheric factors escalates the choking smog to a regional level. This is when it becomes complicated.

Transboundary haze episodes regularly descend into political finger-pointing among the countries involved, even as parties scramble to control fires and offer assistance.

This year, the Indonesian Environment Minister, Siti Nurbaya Bakar, claimed Indonesian meteorological data revealed Malaysia’s haze was not coming from Indonesia. This was refuted by her Malaysian counterpart, Yeo Bee Yin, using evidence to the contrary from the Asean Specialised Meteorological Centre.

In the ensuing diplomatic back-and-forth, Indonesia then announced that four of the 30 oil palm concessions seized for investigations into the fires had Malaysian links.

A political tinderbox

Set against the backdrop of the protracted drama that is the EU palm oil “ban” (where the EU is phasing out the use of palm oil for biofuel due to sustainability concerns), it resulted in mixed messages from the Malaysian authorities.

While Yeo maintained all companies, Malaysian or otherwise, should bear the legal brunt of their practices, the Malaysian Primary Industries Minister, Teresa Kok, chided Indonesia’s open linking of the haze to palm oil, which she said was “playing right into the hands of anti-palm oil campaigners”.

Indonesia and Malaysia are the world’s largest producers of palm oil, the most widely consumed vegetable oil today. Its importance for the development and economies of both countries, coupled with the negative environmental effects of the crop, has made the industry a political tinderbox.

This underlines the enormity of the transboundary haze problem in Southeast Asia: it’s not only a physical problem of land use and weather patterns, but also a highly political one.

These sensitive peatland ecosystems are protected from development by various laws in Indonesia. However, the high demand for agricultural land has led to large areas of peatlands being given out to well-connected concessionaries.

These companies, implicated in illegal land use and fire, continue to be protected by authority figures, both locally and in their home countries.

Both Indonesia and Malaysia, facing the threat of declining palm oil exports to the EU, vehemently deny claims of unsustainability within the industry, while at the same time contending with such industry-related environmental crises.

The awkward reality is that many of the major palm oil producers in Indonesia are joint ventures with Malaysian and Singaporean companies. This makes it diplomatically difficult for Indonesia’s neighbours to come down too hard on Indonesia.

The problem with peat

Peatlands are naturally flooded all year round. Their waterlogged condition pauses the decomposition process, effectively locking carbon underwater in perpetuity. Because of this, peatlands are considered excellent carbon sinks.

The drainage of peatlands as part of the land preparation process kick-starts the decomposition process and releases large amounts of carbon into the atmosphere, speeding up climate change. It also has the added unfortunate side-effect of abruptly drying out the exposed peat, making it very fire-prone.

When fire is then used to clear the land, the resultant blaze produces smoke that is thick, sooty and hardy enough to travel across vast distances. The fires burn the peat soil itself and go deep underground, making it notoriously hard to put out flooding or sustained heavy rains.

Peat fires are especially dangerous because they send toxic particulate matter up into the air. These tiny particulates, as small as 2.5 microns (PM2.5), easily enter into the lungs and cause both acute and chronic respiratory, dermatological, and ophthalmological problems.

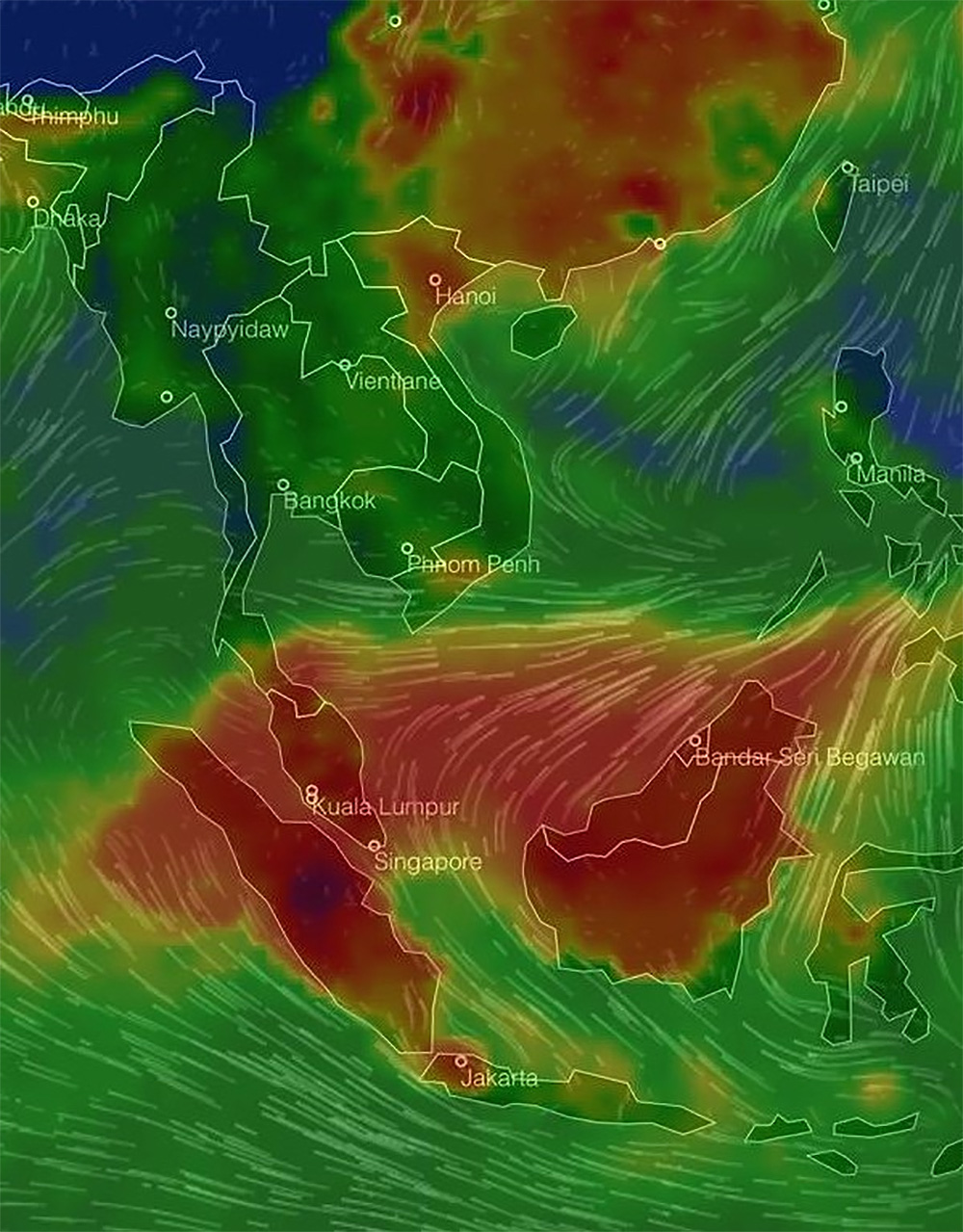

The cyclical El Niño weather pattern creates especially hot and dry temperatures every few years, which worsen the fires. When coupled with the Southwest Monsoon winds that push warm air from the southern part of the region upwards, the smoke produced by these fires travels across national boundaries, making the haze “transboundary”.

In especially severe years, transboundary haze can affect up to six Southeast Asian countries.

A recent Harvard University study found that these particulates have contributed to tens of thousands of premature deaths in Indonesia and many more across the region.

This year, a moderate El Niño and strong Southwest Monsoon winds pushed the smoke from the Riau and Jambi regions of Sumatera to Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore, while smoke from fires in Kalimantan was blown across to East Malaysia.

Smaller fires in Malaysia also contributed to the haze locally - Sri Aman’s severe haze was due to both local and foreign smoke.

What’s new this year?

Just prior to this current haze season, Indonesia announced it would make its moratorium on all new deforestation activities, including for oil palm and peatland, permanent. While this announcement was heartily welcomed, there remains the question of implementation, which continues to be a challenge in decentralised Indonesia.

In Malaysia, after a long wait (many years after Singapore), API readings have finally been announced using PM2.5 parameters, and not the less dangerous PM10. However, these readings are still 24-hour averages, which gives a less-than-accurate indication of air quality compared to hourly updates, which is what is provided in Singapore.

Furthermore, a new directive allows schools to unilaterally close once APIs reach 200, without having to wait for approval from the Education Ministry. However, both countries still seem reluctant to take more decisive action. Indonesia steadfastly refused to accept any assistance from neighbouring countries to help with firefighting efforts this time around.

Malaysia, in turn, announced that an emergency will only be declared once the API reaches 500 (emergencies have been declared based on lower APIs in the past). Despite vehement calls from the public for an exterritorial legal instrument à la Singapore’s 2014 Transboundary Haze Pollution Act, the government remains cautious.

Asean: A region under fire

Due to the relatively-haze free years of 2016-2018, spirits and hopes were high that the region would achieve its vision of a transboundary haze-free Asean in 2020.

Indonesian President Jokowi Widodo even highlighted this during his re-election campaign, announcing proudly that his administration’s efforts have resulted in Indonesia no longer being an “exporter” of haze. Indeed, early on in his first term, he hinted that Indonesia could solve the haze problem without Asean’s “help”.

However, this year’s episode highlights there is still much to be done, both at the national and regional level.

Prevention before the fires flare up again is key. Once the haze dissipates this year, Asean nations should not fall back into the familiar “out of sight, out of mind” mentality that takes away the urgency of sustained prevention efforts.

Asean has been the go-to platform for regional transboundary haze cooperation for more than three decades. While the effectiveness of this platform has been plagued by political limitations due to sovereignty concerns and “good-neighbourliness”, this is not a sustainable pattern of engagement.

A framework that allows for more immediate, effective and sustained action and assistance already exists through the Asean Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution. How bad must the haze be this year to finally compel all the countries involved to take advantage of it?

(This feature first appeared in Trident Media.)

HELENA VARKKEY is a senior lecturer at the Department of International and Strategic Studies, Universiti Malaya. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.