When Ismail Sabri Yaakob delivered his inaugural address to the nation as the new prime minister, he declared his intention to create a “Keluarga Malaysia”.

This was an important call, as only through the creation of a compact comprising the government, business and the people can solutions be found to deal with Malaysia’s debilitating economic and health crises.

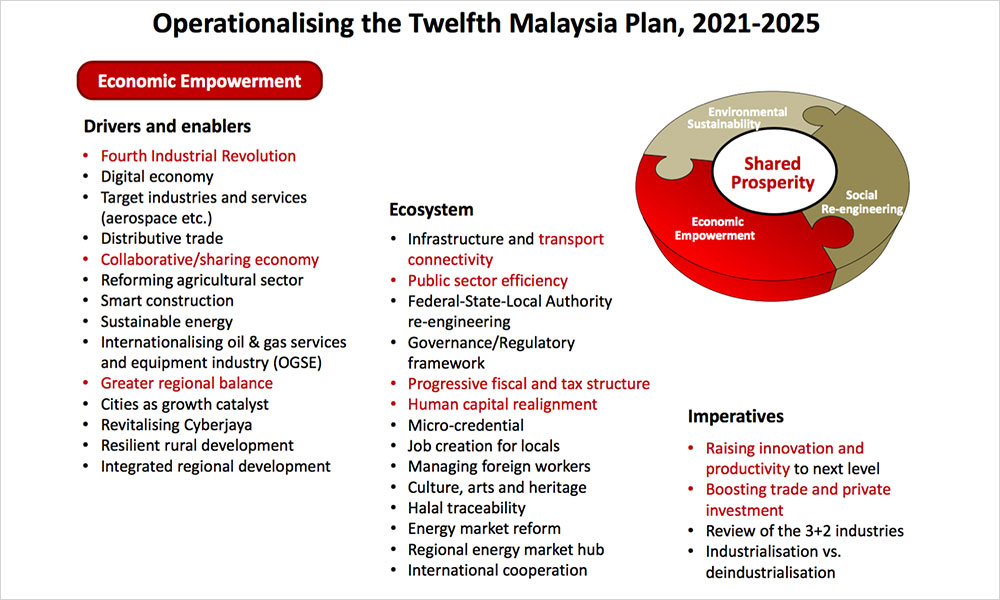

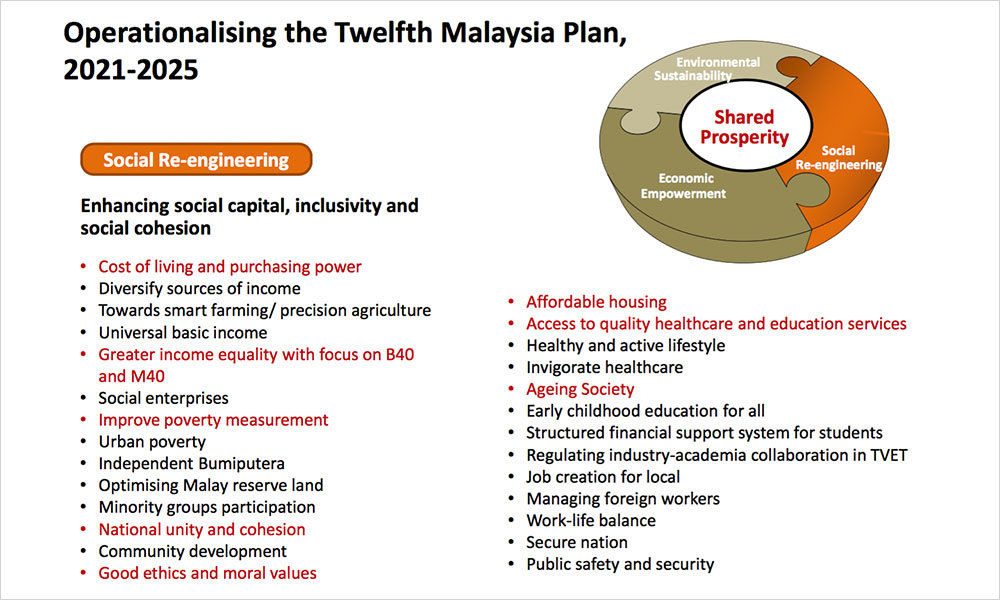

Much was thus expected of the 12th Malaysia Plan 2021-2025 (12MP), the government’s five-year strategy to lead the country out of this unprecedented dual crisis while promoting economic growth and resolving longstanding social inequities.

However, soon after the 12MP was released, strong protests, tinged with a sense of injustice and utter despair, have been voiced that drew attention to the hollowness of Ismail Sabri’s pledge to create a Keluarga Malaysia.

Equitable outcomes?

One “Priority Area” of the 12MP is “Achieving an Equitable Outcome for Bumiputera”. This has been a priority area for the government since 1970, when the New Economic Policy (NEP), a 20-year affirmative action plan, was introduced, after the riots in 1969.

There was a need for an initiative of this sort as Malaysia was then characterised by a social structure, predicated on an ethnic division of labour, where groups were confined to particular occupations and industries.

Bumiputera under-representation in tertiary education and upper occupational positions, as well as in ownership of corporate equity, was stark, while more than 60 percent of the population was mired in poverty.

Malaysia’s method to redistribute wealth equitably was by creating public enterprises, trust agencies and statutory bodies, now collectively called “government-linked companies” (GLCs), to acquire 30 percent of corporate equity on behalf of the bumiputera.

The NEP was supposed to end in 1990, as government leaders were worried that the long-term implementation of ethnic-based preferences might divide the nation.

However, because bumiputera still do not own 30 percent of Malaysia’s corporate equity, this has served as the reason for the continued implementation of ethnically targeted public initiatives, even as debates persist about the economic and social repercussions of such a policy.

Repeated controversy

A huge debate, like the one now transpiring, occurred after Abdullah Ahmad Badawi as prime minister called for public feedback on issues to be dealt with in the 9th Malaysia Plan, 2006-2010 that was being prepared.

When a report submitted by the think-tank Asli raised questions about the validity of the government’s equity ownership figures, even suggesting the 30 percent figure had been exceeded, a massive debate was ignited.

Subsequently, more questions emerged when the government revealed that these figures did not include the corporate equity held by the GLCs. However, the methodology for tabulating these corporate ownership figures was not revealed, nor did the government disclose the volume of corporate equity owned by public institutions.

In 2009, when Najib Abdul Razak was appointed as prime minister, he had to deal with an economy mired in a deep recession, a consequence of the global financial crisis that had erupted the year before.

After assessing Malaysia’s economic problems, Najib announced that affirmative action would cease, to usher in a new era of inclusiveness, in line with his “1Malaysia” slogan that stressed a national – not ethnic – identity. To support his decision, Najib revealed that of the RM54 billion worth of equity that had been allocated to the bumiputera since 1971, only RM2 billion was still held by them.

This was why bumiputera equity ownership then amounted to only 19.4 percent, four decades after the NEP had been introduced. DAP’s Lim Guan Eng referred to Najib’s disclosure as a “scandal” and called for a royal commission to investigate what he saw as shares being given to “BN cronies”.

Nothing came of Lim’s call for an inquiry into the mode of distribution of corporate equity meant for bumiputera.

Meanwhile, when Najib’s race-blind approach was questioned, including by former prime minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad, ostensibly because this agenda side-lined bumiputera concerns, affirmative action was re-cast as one that would be “market-friendly” in the 10th Malaysia Plan 2011-2015.

After BN fared badly in the 2013 general election, Najib reversed his call to end race-based policies. Najib’s disappointment with what he saw as the abandonment of non-bumiputera electoral support was well-captured in an infamous headline in the Umno-controlled newspaper, Utusan Malaysia, “Apa Lagi Cina Mahu?”.

When the 11th Malaysia Plan 2016-2020 was tabled, Najib announced his Bumiputera Economic Empowerment Policy which would be implemented by the GLCs.

Different parties, same rhetoric

Before the 14th general election in 2018, the Pakatan Harapan coalition, now led by Mahathir, declared in its manifesto that its policies would be needs-based. However, after unexpectedly securing power, in September 2018, Pakatan convened a Congress on the Future of Bumiputeras & the Nation.

Mahathir stressed at this congress the need to reinstitute the practice of selective patronage, targeting Bumiputeras. The following month, when Harapan released its first public policy document ‘Mid-Term Review of the 11th Malaysia Plan’, it emphasised that the bumiputera policy was imperative.

Later, when Harapan launched its 10-year roadmap, ‘Shared Prosperity Vision 2030’ (SPV), three objectives were stressed: Development for All, entailing restructuring the economy; Addressing Wealth & Income Disparities, where no one would be left behind; and Nation Building, to create a united, prosperous and dignified nation.

The SPV’s objectives were strikingly similar to those of the NEP, with the same ultimate goal of unifying Malaysia. The key authors of the SPV were reputedly closely associated with Mahathir’s party, Bersatu, led by Muhyiddin Yassin.

It was no surprise then that when Bersatu broke away from Harapan to combine forces with Umno, the stress of the new Perikatan Nasional government under Muhyiddin was on promoting the bumiputera agenda. Muhyiddin’s government would stress the implementation of the SPV, a reason why the 12MP has a strong ethnic-based agenda.

The equity question

There is evidently little political will by politicians in power to have an honest debate about the viability of ethnic-based policies to resolve socioeconomic inequities, even when confronted by a serious economic crisis.

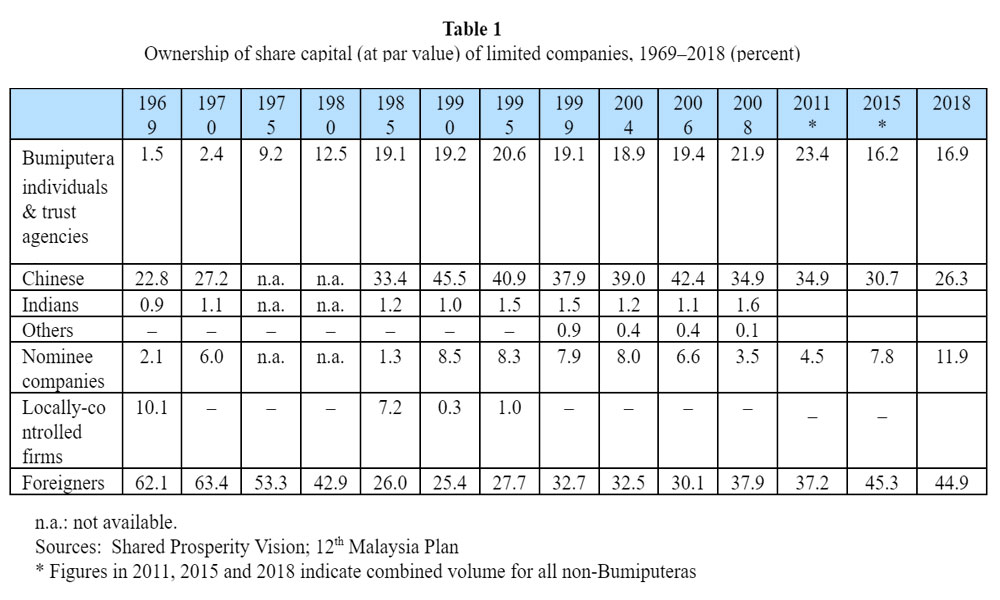

And yet, a close assessment of the equity distribution figures disclosed in the 12MP indicates an urgent need to review ethnic-based preferences in national policies. In fact, it appears that there is an attempt in the 12MP not to disclose the severity of the problem as the equity distribution figures provided are only for 2015 and 2018.

There was no attempt, unlike in previous Malaysia Plans, to show how equity ownership patterns have evolved since 1970 when the NEP was introduced.

Table 1 (below) indicates the corporate ownership figures between 1969 and 2018, drawn from the previous Malaysia Plans. These figures, seen from a longue durée perspective and based on the government’s tabulation, indicate that the volume of bumiputera-owned equity reached its highest point of 23.4 percent in 2011, though it has since fallen appreciably to 16.9 percent, a figure lower than in the 1980s. Among non-bumiputera, the situation is equally alarming.

The total equity of 26.3 percent attributed to non-bumiputera in 2018 is less than what was owned by these ethnic groups in 1970. This fall was particularly steep between 2006 and 2018, a massive 16 percentage points. The 12MP drew no attention to this steadily declining volume of equity owned by all Malaysians, a disclosure that would surely lead to questions about why this is the case.

Meanwhile, the volume of equity owned by foreigners has increased substantially, by nearly 20 percentage points, since its lowest point in 1990.

What is similarly disconcerting is that the government continues to allow the use of nominee companies, a method employed to shield from the public eye the beneficial owners of corporate equity. There has been a palpable increase in the volume of equity owned by nominee companies over the past decade.

What is not disclosed at all is the volume of equity owned by public institutions or the GLCs. The GLCs undoubtedly have a huge presence in the economy and if their corporate holdings are not included, the equity figures in the 12MP are a complete misrepresentation of the equity distribution pattern in Malaysia.

Honest debate needed

Ethnic-based policies to address socioeconomic inequities have evolved as an avenue for politicians to secure unfettered access to government resources to consolidate power. Questions repeatedly asked over the past two decades must now be answered.

When corporate equity was redistributed to public institutions and bumiputera, who were the beneficiaries? Does the huge fall in equity ownership by non-bumiputera mean that they are not investing in the economy because they fear the expropriation of their enterprises through such policies? The current controversy about the 51 percent bumiputera equity ownership stipulation in freight forwarding enterprises is a case in point.

Other questions require a response. Where do the GLCs fit in this debate about corporate equity distribution? That GLCs can be abused by politicians to consolidate power was patently exposed when Perikatan took control of the government in 2020.

Muhyiddin appointed sitting MPs as directors of GLCs to ensure their support of his position as prime minister. Interestingly, during the parliamentary debate about the 12MP last week, Muhyiddin, now out of power, called for a review of the role of the GLCs in the economy.

Mahathir had similarly called for a review of the role of the GLCs during the 2018 election campaign because he claimed, they had been persistently abused by government leaders though these institutions served to help bumiputera acquire a presence in the corporate sector.

Mahathir repeatedly mentioned that Mara, Tabung Haji and Felda, institutions created to help Bumiputeras in need, were ensnared in scandals. Yet, Mahathir, as Pakatan’s prime minister then, did not dismantle this debilitating patronage system, an outcome of ethnic-based policies, that had contributed to grand-scale corruption.

All politicians who have served as prime ministers between 2003 and 2020 have openly or tacitly acknowledged that they are aware that ethnic preferences should be discarded. Ismail Sabri knows this.

So, if the stated objective of the 12MP is to “achieve a prosperous, inclusive and sustainable Malaysia”, how can this goal be achieved when not all Malaysians are accorded equal access and fair participation in the economy?

If Ismail Sabri expects his Keluarga Malaysia slogan to be taken seriously, national policymaking cannot be distorted through the continued practice of selective patronage and ethnic targeting in business. - Mkini

TERENCE GOMEZ is former professor of Political Economy at Universiti Malaya. His publications include 'The New Economic Policy in Malaysia: Affirmative Action', 'Horizontal Inequalities and Social Justice' and 'Minister of Finance Incorporated: Ownership and Control of Corporate Malaysia'.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.