Power and the money, money and the power.

So goes the 1995 hit song "Gangsta's Paradise".

Indeed when it comes to coal-fired energy, the two are intertwined. One cannot separate the business of coal power from money matters. Simply put, no money, no coal energy.

Recognising this, in the global race to reduce carbon emissions and address climate change, several of the world’s largest advanced economies have recently delivered a strong message — an end to the gravy train of funding for all new international coal-fired plants.

This was most recently announced by China — the world’s largest emitter of harmful greenhouse gases and the biggest public funder of overseas coal plants — followed by South Korea and the G7, comprising the United States, Britain, Canada, France, Germany, Italy and Japan.

South Korea and Japan are the second- and third-largest financiers of coal plants abroad.

But what about Malaysia?

Heavily invested

Malaysia — where coal fuel currently contributes to almost half of the energy supply — is lagging far behind the international financial decarbonisation curve.

Despite the country’s long-running global pledge to drastically cut carbon emissions and reduce its carbon footprint, and, despite Prime Minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob’s recent vague declaration during the tabling of the 12th Malaysia Plan to cease building new local coal-fired power plants, there’s been no formal public commitment to phase out the funding of new coal projects, domestically or abroad.

Nor has Ismail Sabri hinted that any such plan is in the offing.

Coal-related funding can be for any part of the value chain, from building and operating coal-power plants to investing in other coal-related activities like manufacturing coal mining equipment to shipping and transporting the material.

Up to last year, the country’s major government-linked commercial banks — namely CIMB Group, Maybank and RHB Bank — were still heavily investing in the coal sector.

This included providing services such as lending, investing, fundraising, syndicating, advising or underwriting at home and abroad.

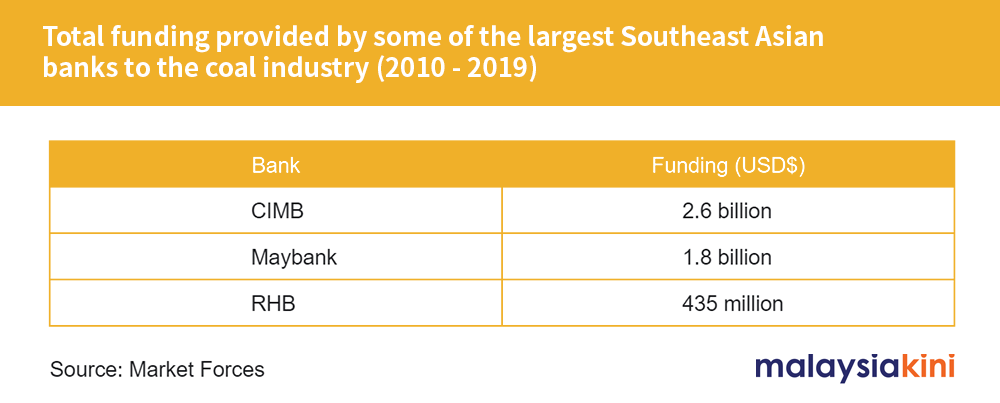

According to Australia-based finance and climate NGO Market Forces, the three banks, among some of the largest in Southeast Asia, are estimated to have funded over US$4.9 billion (RM20.5 billion) from 2010 to 2019, with CIMB providing over US$2.6 billion (RM10.88 billion), Maybank US$1.8 billion (RM7.53 billion) and RHB US$435 million (RM1.8 billion) through bonds and loans.

(Maybank is the fourth-largest bank by assets in Southeast Asia, followed by CIMB (fifth) and RHB (13th).)

Not long after the Market Forces report came out last year, Maybank and CIMB came under heavy criticism for reportedly funding the controversial planned 2,000MW Jawa 9 and 10 power project in Banten in Indonesia, among others.

The US$3.5 billion (RM14.64 billion) project, part of neighbouring Indonesia’s largest coal-fired power plant complex, is expected to begin operations in 2024.

Since the South Korea-backed venture was announced, environmental groups like Greenpeace have sounded the alarm, warning that the project could cause up to 4,700 premature deaths during its 30-year lifespan.

CIMB is also listed as among the top 20 lenders to coal mining activities in Australia between 2016 and 2019. Peninsular Malaysia derives 22 percent of its coal supplies from Down Under.

Additionally, German green group Urgewald estimated that CIMB pumped close to US$2 billion (RM8.37 billion), Maybank US$1.8 billion (RM7.53 billion), and RHB US$363 million (RM1.5 billion) in coal investments between October 2018 and October 2020.

Among the alleged recipients is Genting Energy, part of Genting Berhad, which co-owns the Meizhou Wan power plant in China and a majority share in another Banten power plant in Indonesia, all generating energy from coal.

Banks get green inspiration

In the course of a year, however, the banks have experienced a sea change when it comes to their policy on coal.

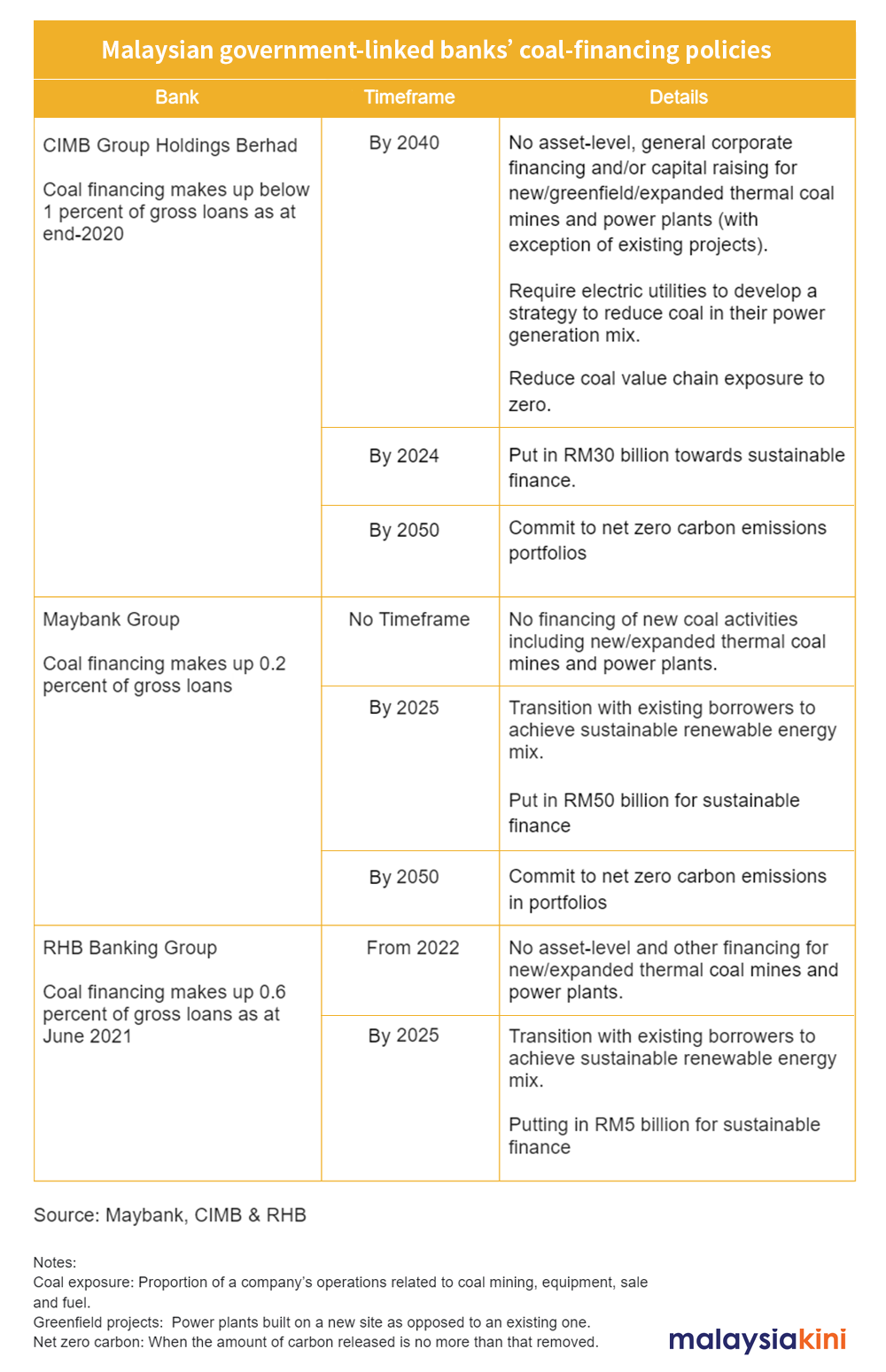

Since then, all three financial houses have announced the eventual phasing out of new coal financing from their respective portfolios (see table).

CIMB got the ball rolling in late December last year, declaring itself the first Malaysian and Southeast Asian bank to do so, followed much later by Maybank in May this year, and RHB in June.

Perhaps due to a lack of clear federal policy to lead the way, the banks’ coal policies differ in clarity, priorities, timelines and degrees of commitment.

Environmentalists, like PSM Bureau for Environment and Climate Crisis national coordinator Sharan Raj, believe the policies are still “quite weak” and afford them much wriggle room.

Apart from no specific short, medium and long-term strategy outlines, Sharan said the banks have failed to specify whether they would also cease all new domestic coal-related financing services, and to spell out clear exclusion criteria for clients.

For example, what do banks mean when they say 'no new coal financing'? Does this only cover new coal-energy plants and mining operations, or the entire coal value chain, including manufacturing of coal mining equipment and shipping?

Furthermore, where does this leave existing projects within the coal energy sector, such as the contentious Jawa 9 and 10 units in Indonesia?

While CIMB Group and Maybank have said they will honour existing commitments, the banks declined to comment on specific clients.

Besides the three major government-linked banks, other Malaysia-based financial institutions have also announced coal-specific policies.

This includes Public Bank Berhad which pledged to cease financing of coal mining and production activities, while Affin Bank Berhad, another government-linked bank, pledged to restrict its insurance business’ investments in coal mining and coal-based power generation companies.

The devil’s in the details

Sharan said the lack of specificity is not unique to Malaysian banks but is a perennial complaint by environmental groups about pledges made by the world’s funders of coal energy.

“Take the G7 pledge. The decision (to no longer support unabated international thermal coal power generation) looks good. But the devil is in the details.

“It is, in fact, very hypocritical where (the governments) have made lots of caveats for themselves,” he said.

Similarly, he said, Ismail Sabri’s commitment to turn Malaysia into a carbon-neutral nation by 2050 “at the earliest” and to eventually replace coal-power plants may have been announced in the Dewan Rakyat, but it is not legally binding.

“All of these decisions are executive decisions. It is not backed by statutes, it is not backed by Parliament and there is no act controlling minister’s powers,” Sharan said.

In short, this leaves the door open for the possibility, however narrow, of any future government to backtrack on this pledge.

The same would also apply to domestic funding by banks, many of which, Sharan pointed out, fall under government control.

“As long as the government does not approve any new (coal) power plants, there won't be the issue of securing funding, but... should the government build a new power plant (tomorrow), the funding will come in, no problem.

“That’s how things work in Malaysia,” he said, noting the absence of restrictions against Malaysian banks from funding overseas coal sectors.

The motivational power of 'self-interest'

So, if banks in Malaysia aren’t bound by any coal financing restrictions by Putrajaya, why the shift away from coal?

The answer is not a sudden development of a green perspective.

According to the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), a think tank that tracks financial sector policies on coal power generation and coal mining, the greater Asian region represented 20 percent of all new improved policies introduced globally over the last three years.

That has grown to 40 percent this year alone, including policies by the three Malaysian banks.

IEEFA Energy Finance Studies (Australia/South Asia) director Tim Buckley said banks today just have no choice but to deliver on various environmental, social, and governance (ESG) funding commitments.

The reason is simple — shareholders want them to.

“A couple of years ago, they (banks) hadn't even drunk the (green) Kool-aid. Now they’re actually running as fast as they can. Self-interest is a powerful motivator,” said Buckely, who himself worked with CIMB early last year prior to the bank developing its coal sector guide.

Buckley explained that Malaysian banks would likely not have committed to such low-carbon and coal exit policies if not for two things — the “reading of the tea leaves”; and a strong signal from Malaysia’s central bank.

In the former, he explained the banks were likely emboldened by the global shift away from fossil fuel and towards greener — and cheaper — renewable energy.

"If you build a coal plant, you're tied to buying coal (to fuel the plant) for the next 40 years to power it.

“You build a solar project, you’ve got free electricity for 25 years. These are financial products, not commodities.”

Further, he said, the “tea leaves” are showing that global capital is likely to be deployed in zero-emission industries in the future.

“(The banks are saying) let's get ahead of the curve. Let's create the products and then get rewarded as a bank for being a leader because the global market is gonna move (in that direction) anyway.”

On his second point, Buckley speculated that the financial institutions were also feeding off signals given by Bank Negara Malaysia “for the greening of the financial system”.

“It's about creating the right policy and the right financial frameworks... there's no way (banks) would have had the willingness to make that commitment if the Malaysian central bank hadn't already... given them the room (to do so).”

Cutting coal funding could also have a detrimental social impact in power-hungry developing countries where banks like Maybank and CIMB have exposure to coal-fired power plants.

Among efforts taken by the central bank include its Climate Change and Principle-based Taxonomy (CCPT) that help banks assess and classify their green activities, and its involvement in the Joint Committee on Climate Change to strengthen the financial sector’s capacity in managing climate-related risks.

No quitting cold turkey

But as self-motivated as the banks are, Buckley said banks cannot just divest from the coal energy sector cold turkey.

Hence the move to phase out related financing over a longer time period.

“There’s no cutting and running tomorrow. At the end of the day, financial institutions have an obligation to their existing client base...If you built a project five years ago, it's gonna run for the next 20 or 30 years. You still need debt funding (and insurance) for that project.

“It's about working within the existing investments, the existing commitments, and just helping the management of those companies to understand the opportunities (to transition to greener ventures),” he said.

Cutting coal funding could also have a detrimental social impact in power-hungry developing countries where banks like Maybank and CIMB have exposure to coal-fired power plants.

In fact, according to its 2020 sustainability report, Maybank warned that an immediate stop to coal fuel financing could have “severe economic and social impacts to the (Asean) region” where over one-third of the energy is supplied by coal.

“Globally, the world is reaping the impact of the Industrial Revolution that has allowed developed nations to reach their economic status from the utilisation of coal.

"As such, it would be beneficial to all if these nations help provide solutions and subsidising mechanisms that can help developing markets progress towards alternative fuel sources,” Maybank’s chief sustainability officer Shahril Azuar Jimin said in a statement to Malaysiakini.

Apart from electricity security, it is also a matter of job security for the local communities.

“If you screw the owner of the (power) plant, you screw the workers and you screw the community. That's not a transition at all. If you leave it just to the financial markets, that's what will happen,” Buckley said.

All the more reason, he said, for governments like Malaysia to get involved to manage this transition strategy instead of leaving it to the free market.

“Don't expect the financial market, the private market and the global capital market to suddenly grow a conscience. They won't.”

Editor’s Note: Malaysiakini contacted the Sustainable Energy Development Authority (Seda) and the Energy and Natural Resources Ministry for comment. Both said they would be issuing a response, but have yet to do so at the time of reporting.

Additional information came from Kim Ji-Yoon of Korea Center for Investigative Journalism (KCIJ)-Newstapa and Annelise Giseburt of Tokyo Investigative Newsroom Tansa.

This series of articles is supported by the Judith Neilson Institute’s Asian Stories project, in collaboration with Tempo, the Centre for Media and Development Initiatives, Tansa, The Australian Financial Review and Korea Center for Investigative Journalism (KCIJ)-Newstapa.

-Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.