Hania is an Information Technology (IT) Engineering student at a private university in Malaysia, but she is not like her classmates.

Having fled Pakistan, the top-scoring student is living in a country that does not recognise refugees, making it difficult for her to access even the most basic of education, let alone tertiary education.

She is also an anomaly among her refugee peers, for Hania is one of five recipients of the Fugee’s HiEd Scholarship, an academic scholarship programme for refugees.

Fugee programme director Abdulmajid Chahrour said it was the hardest task of his life - picking five candidates who would receive the scholarships among more than 300 applicants.

“The first round of shortlisting saw 124 candidates and we shortlisted them down to 15 candidates to be interviewed. If we had sufficient funds, I would have given it to all 15 of them,” said the 26-year-old Palestinian.

“We are proud to be the first NGO in the country to provide scholarships to refugees pursuing a degree programme,” he said.

Before this, scholarships for refugees have been granted by universities and corporate bodies.

The other four recipients of the Fugee scholarship are youths who had fled Palestine, Afghanistan and Pakistan, respectively. They declined to be interviewed.

One of them, Chahrour said, had just lost his father to the Covid-19 pandemic and was working full time to support his family while pursuing a full-time degree in computer science.

“The women, too, had faced huge obstacles from family members and having to convince them that women, too, deserved an education was a different but difficult battle for them,” he said.

At RM5,000, the annual scholarship could pay the fees for an entire year for some, or cover up to 70 percent of their needs, for others.

“We hope to raise enough funds to be able to fully fund 10 students for the 2023 academic year,” he said enthusiastically.

From a tuition class of four students

What started as a tuition class for four students in 2009, the Fugee School in Gombak, Selangor, now provides primary and secondary education for 200 children, mostly from the Middle East and Greater Middle East regions, including Somalia and Pakistan.

The school grew and expanded its scope as the needs of the students grew and today, it was time to look at opportunities for the tertiary education of refugee youth, he said.

Although Hania had already commenced her degree in IT Engineering in Lahore before she fled, she received no exemptions to modules when she finally got accepted into a local, private university. She had to start from scratch.

Still, she is grateful for the opportunity, which previously had been refused to her simply because of her refugee status.

“I feel so blessed and I will do my best to help other refugees in Malaysia.

“I have been in Malaysia for more than five years and it has been severe mental torture not knowing how I was going to support my family when we got resettled.

“It has been torturous to not get a decent job and all the jobs that were available were ones that I would not have even imagined doing back home,” the 24-year-old said.

With two siblings to support, Hania said her refugee status was always the single reason for all the rejections she received, be it applications to universities or for employment.

Donations matched with 50pct top-up

According to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), 45,650 refugees living in Malaysia are below the age of 18 years, so the deluge of applications for the scholarship was no surprise for Chahrour.

He said the programme was designed to address the alarming reality of a five per cent enrolment rate in higher education among refugees globally, compared to 39 percent for non-refugee youths worldwide.

It is worse in Malaysia, as in 2016, UNHCR data showed only 48 refugees in Malaysia were enrolled in higher education institutions, he said.

The programme also acknowledges that the students need more than just money for fees, he said.

“Through the scholarship programme, students will also receive career counselling, technical and vocational training, mentorship from professionals in their respective fields and assistance in finding internship placements.”

With the first round of scholarships funded through private donations, Fugee School is now seeking to crowdfund to help more students.

Using the grassroots fundraiser website GlobalGiving, the group hopes a special campaign next month could boost donations so more students can be assisted.

In the “Little by Little” campaign, GlobalGiving would match donations with 50 percent top-ups for every donation received from April 4 to 8.

“Any little amount, whether one-off, monthly or yearly pledges, will grow by 50 percent during these four days.

“Donors have multiple choices on how they can contribute. They could choose from footing just the registration fee to supporting a student’s tuition fee for a whole year,” he said.

In addition to that, outside the four-day campaign, donors pledging monthly would have their donations matched with a 100 percent top-up after the fourth month, he said.

Helping young refugees to see beyond their current reality

Chahrour said the Palestine Embassy is also planning to set up an education fund in collaboration with Fugee.

He said this would attract donors familiar with the Palestine Embassy, who could help fund education programmes for refugees in Malaysia, including the Fugee School.

Walking through crowded classrooms that occupied two floors of shop lot units, Fugee School principal and director of education, Kudzai Charlton said the school provided an inclusive environment.

The school caters to 200 students from kindergarteners, who start at age four, up to 19-year-olds pursuing their general education diplomas.

Charlton said the school aims to help students pursue their education to a higher level, “and for them to be able to see beyond what their current reality was”.

“Here, they don’t feel like refugees, and this was clear when they shared their dreams with us.”

The school also exposes students to a variety of cultures, including Malaysian culture, to help them better integrate with society.

“We have created a safe environment like an international zone where they could easily communicate with each other without noticing their differences,” he said.

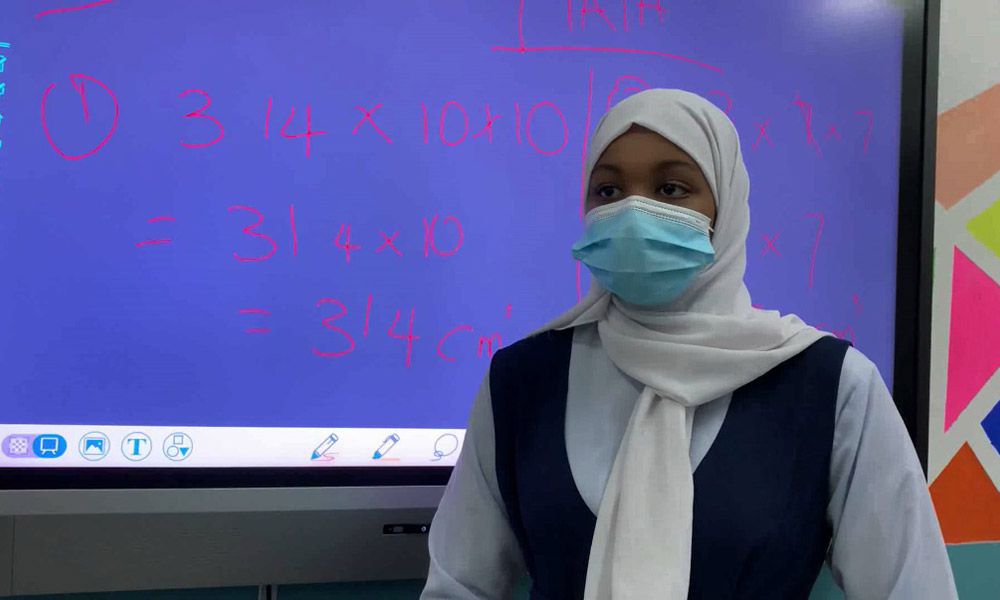

Charlton, who came to Malaysia as an international student from Zimbabwe and stayed on to work here, explained that while students still used workbooks, some classrooms were equipped with smartboards, others with projectors and the kindergarten classes were equipped with TV Screens to aid interactive learning.

The 33-year-old said the pandemic forced them to expand their reach through digital devices and they managed to do so mainly thanks to donors who gave tablets and even paid for internet data for some of the students.

Yursar, a 17-year-old Somali refugee born in Saudi Arabia, said she feels fortunate to be able to attend Fugee School.

Before enrolling, she spent her first two years in Malaysia mastering the English language.

“I couldn’t speak any English when I came to Malaysia so I stayed home and studied English.

“But when I joined the Fugee School, I found that I had forgotten Math and Science, but I have caught up now,” she said, eagerly adding that she hoped to someday become an investigator for agencies like the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation.

For teacher Salma, teaching English, Mathematics and Science at the school for the past four years has inspired her to do better every day.

“They make me forget that I was a refugee, too. I forget my stress and troubles,” said the Somali refugee who grew up in Kenya.

Recounting a memorable moment, Salma said a class she taught in grade four was so excited to have her as their teacher three years later when they started seventh grade.

“They touched my heart because it showed me that I had made an impact in their lives,” said Salma, who sometimes works after hours to assist her students with their schoolwork.

Finances not the only hurdle

Obtaining funding for fees, however, is just one obstacle for refugees seeking to enrol in higher education in Malaysia.

One key obstacle was the required documents for enrolment.

Those enrolling as international students in Malaysia must have a student pass or a visa approval, which requires a valid passport.

While some private institutions have enrolled refugees as students, the students still run the risk of their degrees not being recognised upon completion, as their enrolment may not be endorsed by the Higher Education Ministry. Private institutions also run the risk of landing in hot water for doing so.

One university that is seeking government support to create a pathway for higher education for refugees is Monash University Malaysia.

Its School of Business director, Priya Sharma, said the school had before this submitted a proposal to the Pakatan Harapan government for refugees to be allowed to enrol using the UNHCR Refugee cards (URC).

Sharma said her organisation plans to submit the same proposal in a White Paper to the current government, to allow the school to enrol refugees as students, in a pilot project.

Among the proposals is for private higher education institutions that were signatory to the White Paper to be allowed to admit refugees with URC as a valid enrolment document.

“The institutions would be signatories to the White Paper for five years and this would allow us to monitor and evaluate the programme to determine the long-term viability of the initiative,” she said.

Monash University Malaysia is one of several universities which are partnering with UNHCR to provide education and training for refugees.

In 2015, UNHCR signed a memorandum of understanding with the University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus, International University of Malaya-Wales, Limkokwing University of Creative Technology, Brickfields Asia College, International Innovative College and HELP University to provide access to higher education courses for refugee youths.

As a signatory to the United Nations-supported initiative called the Principles for Responsible Management Education (PRME), Monash University Malaysia’s School of Business is also carrying out courses under the Connecting and Equipping Refugees for Tertiary Education programme.

“Through knowledge-sharing and awareness-raising, we hoped to motivate refugee youth to continue their education.

“We helped them develop a strong university application and increased their awareness of some of the skills they would need to succeed in higher education,” she said.

The business school is also working with groups like Fugee to support them through mentorship and project management.

“A collaboration like this between UNHCR, Fugee and PRME, built partnerships that helped bridge the gap between educational institutions, industry and community,” she said.

Besides providing opportunities for higher education to refugees, Sharma said the School of Business can play a role in supporting entrepreneurship among refugees and imparting employability skills, crucial for the refugees’ survival.

“As an institution of higher education, a university is a powerful agent of change,” said Sharma. - Mkini

This article is part of a series on refugees in Malaysia, supported by Japan’s Sasakawa Foundation.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.