As a local journalist interviewing PSM central committee member Dr D Michael Jeyakumar recently put it: "What's there to not like? Perhaps mySalam should be renamed 'mySaham'?"

Well, there's the matter of market failure in the healthcare sector, which neoliberal (free-market) economists tend to downplay, if not ignore.

Kenneth Arrow, the 'father' of health economics, was credited with introducing the notion of informational asymmetry in 1963, which was eventually acknowledged as a major violation of the tenets of competitive free markets, most importantly, the key assumption of informed and sovereign consumer choice.

Take for instance your visit to a private medical practitioner. As an average layperson, we have come to internalise as normal a highly unusual transactional scenario: the seller (doctor) tells the buyer (patient) what the buyer must buy - investigations, procedures, medicines, referrals.

The patient, of course, can seek second opinions, or shop around, but eventually, you pretty much do what your doctor tells you. Hence the importance of professional ethics in this profoundly unbalanced doctor-patient relationship characteristic of medical practice.

In the UK, the Blairite Labour Party introduced internal market reforms to the National Health Service (NHS) in 1990, but even they never entertained the folly of generalised health vouchers to ‘empower’ the NHS' patients as healthcare consumers and purchasers.

The GPs instead, through their group practices, were provided publicly-funded budgets to purchase from NHS facilities referral and other needed services on behalf of their registered patients.

Even in an affluent, advanced country, the average layperson/NHS patient was seldom in a position to make informed, actionable decisions about their medical conditions, and it was hoped that suitably incentivised (and accountable?) GPs could act on their behalf as ‘proxy purchasers’ of referral services and to reduce the 'moral hazards' in medical transactions.

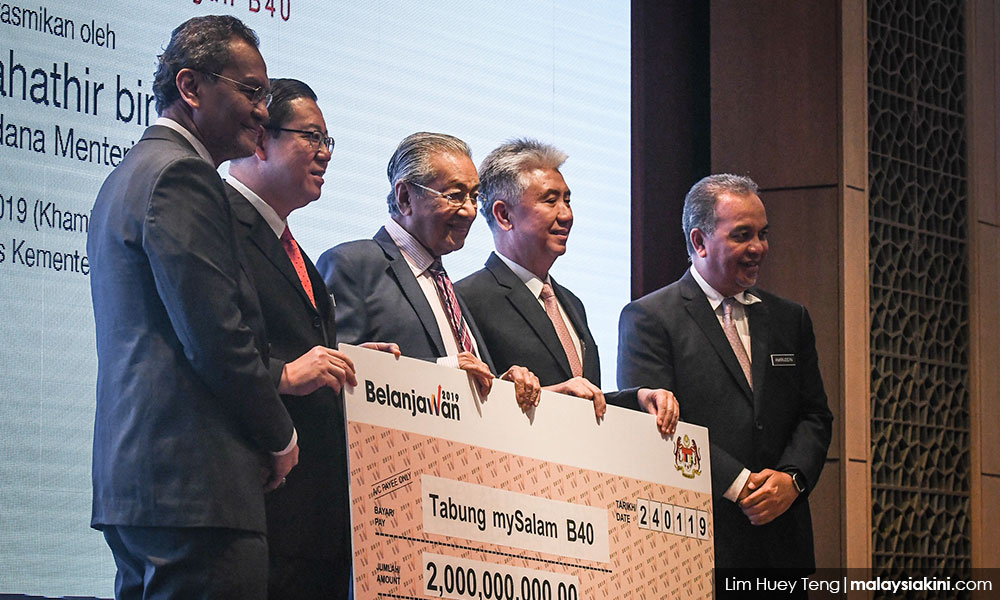

In contrast, mySalam is an unmediated patient health voucher scheme which disburses a lump sum of RM8,000 to eligible enrollees upon diagnosis of one of a list of 36 critical illnesses, with further daily stipends of RM50 up to 14 days for patients admitted to government hospitals.

It is understandable that bottom 40 percent (B40) households welcome this supplement to help defray the medical expenses incurred in coping with a catastrophic illness, which sadly often renders them vulnerable and manipulable.

It is also understandable that populist politicians and incumbent governments, with an eye towards re-election, easily resort to a modest insurance coverage for the B40, without due consideration for cost-effective and sustainable healthcare systems (low visibility and negligible political returns).

Whether or not this is the best use of a compromise settlement with a foreign insurer, for rehabilitating and strengthening our underfunded public healthcare sector, such that it can equitably deliver no-frills, medically-necessary care of quality to all, on the basis of need, is far from clear.

The finance minister (and health minister) also need to make clear what role(s) if any, private insurers like Great Eastern might play in future reforms in the financing of healthcare in Malaysia. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.