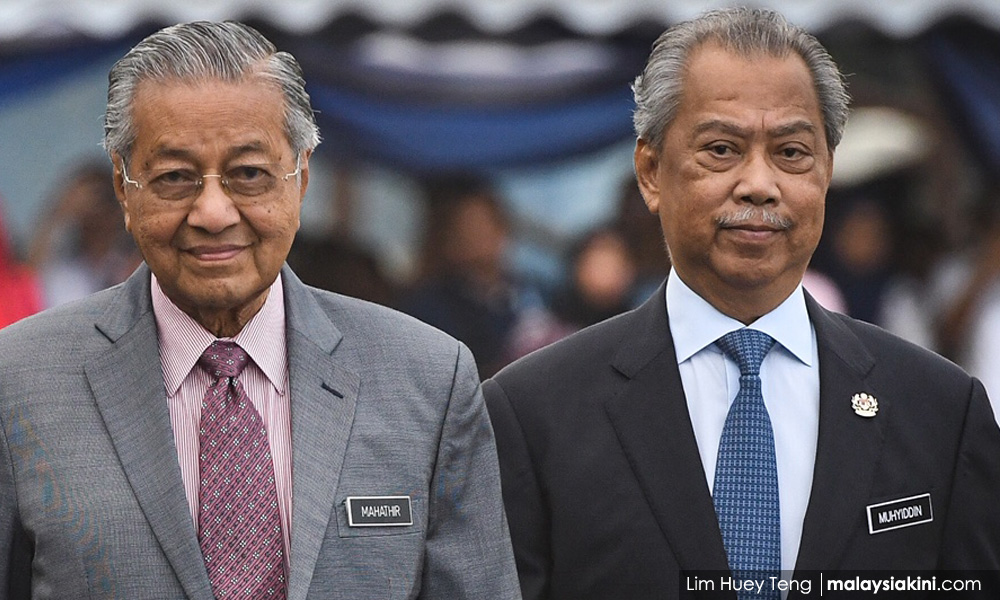

Two months have passed since the infamous Sheraton Move that brought Muhyiddin Yassin into office. He came to power at a time when Malaysia is facing the worst crisis in history – and the pain has only started.

His approach to surviving politically has been three-fold – to make strategic alliances and use patronage to secure a parliamentary majority, to put the country into lockdown to reduce the spread of Covid-19, and to offer immediate short-term financial cash and lending assistance in the hope that this will appease the electorate.

All three are not tenable given the scope of Covid-19. In this period of the movement control order (MCO), the person who is most locked down is the prime minister himself.

Although Muhyiddin has immediately put off facing the opposition by undercutting the parliamentary process with a one-day sitting on May 18, the reckoning will come. Muhyiddin is in fact facing potential opposition from all sides: self-interested politicians, a demanding electorate expecting a resolution to the health crisis – a reality that is much further off than the reported cases suggest – and a suffering electorate that is not yet fully prepared for the economic hardship and sacrifices coming ahead. The massive drop in oil prices, falling demand for palm oil and electronics, as well as rising unemployment will have an unprecedented effect on the economy and society.

The safest way out for Muhyiddin (and Malaysia) is to break free from the political constraints that he has allowed to entrap him and move Malaysia in this period of crisis towards stronger policies and better governance. Covid-19 provides an opportunity for new political arrangements.

The crisis is already reshaping attitudes and the new realities call for different policy approaches that will require broader public support than Muhyiddin currently has. There is an urgent need to reach across the political divides, to tap into the country’s diversity and talent, to find allies that put the country first, not themselves – or their bank accounts. As I suggest below, Malaysia needs a plural umbrella national government.

Indications, however, are that Muhyiddin is opting to extend his own lockdown, and with it a political – and economic – recovery that is harder and longer to reach.

Trapped inside the political cage

Recent events – keeping incompetent ministers in their positions, appointing unqualified people to head government-linked companies (GLCs) and failing to apply the law to politicians who have blatantly violated the MCO – show how much Muhyiddin is beholden to his new political ‘friends’.

Even in a liberal count, Muhyiddin has a slim majority in parliament. He has a total of 113 or 114 seats (a majority of two or three seats) – and this assumes that those inside his coalition are loyal to him – a mistake to do. Sadly, the dominant mode of most politicians is to be loyal to oneself.

The last month has seen political extortion playing out – with disturbing calls for ruling politicians to be given plumb positions while many ordinary people are going hungry. The lesson about blackmail is that it often does not stop – and on the cards are not just the dropping legal cases but worrying distributions of positions that will allow for possible plunder and mismanagement.

Reversing or dropping legal processes will not only cost Malaysians money it hopes to recover abroad and needed investments it hopes to retain and win over, it will leave an indelible impact on the rule of law, already strained by its uneven application during the MCO. These practices will cause havoc at a time that Malaysia needs to save every ringgit and work toward putting the economy on track – not take it back further.

The political situation is treacherous, as those who are willing to sell out principles to make a deal for power are often caught further, and ultimately betrayed. Muhyiddin cannot win in this dynamic, he will be caught by the entrenched patterns of greed and exclusion in the system.

Co-vice 2020

Having kicked parliamentary accountability down the road, the next arena where Muhyiddin will have to make major decisions involves the Bersatu party election – currently scheduled for June. This may be put off further, but this would involve (again) using technicalities and levers of power to undercut the democratic accountability process.

While Muhyiddin may hold onto the party leadership, he is likely to have a party leadership committee that will not necessarily be in his favour. Bersatu’s founding senior leader, Dr Mahathir Mohamad, has stated he is unhappy with the deals Muhyiddin has made. Muhyiddin will effectively be adding a new list of people he will have to appease.

More importantly, he would helm a party that lacks credibility and grassroots – that is unelectable nationally. Even if it reaches seat agreements with Umno and PAS – not an easy process as there is already disgruntlement in the rank-and-file about current appointments – he and his newly-minted Bersatu political allies face serious obstacles in getting elected in their own seats. Gombak, for example, maybe a red zone for the Covid-19 cases, politically it is even redder.

Further, there is no guarantee that Muhyiddin will be allowed to lead again, as other parties are waiting for when polls are eventually called and/or when they have their numbers to be in control.

A possible solution lies with Muhyiddin leaving Bersatu and rejoining Umno, but this path is even more precarious. Muhyiddin may gain enough support for leadership – while holding the prime minister position – but his loyal allies in Bersatu will face a harder time for acceptance.

Also, there is no one Umno. The party is deeply factionalised with at least four major groups tied to different leaders/warlords and a series of ‘independents’ looking for safe (and financially secure) landings. Even if Muhyiddin managed to get a leadership position in Umno, the deals to get there would constrain him and undermine public support. Some in Umno would not hold to the deal as well. Many in Umno appreciate that being attached to a government facing an economic crisis is not in their interest.

Even more challenging is that the baggage of the current Umno – tainted by greed and corruption, relying on mobilising racialised rhetoric and ethnic insecurities and rewarding loyalty over talent – is an even bigger liability for Muhyiddin’s government. Joining forces with those ‘infected’ by greed will cause further spread of the ‘disease’.

Political distancing

What then are the better options ahead to get Malaysia’s leadership out of the lockdown it has put itself in? The answer lies with the same processes used the world over to address Covid-19 – distancing.

Muhyiddin needs to move out of old patterns and reduce his ties with the practices that have undermined the country’s ability to move forward. These include exclusion (racial, economic and gender), corruption by elites who view political positions as entitlements, polarising mobilisation of identity as opposed to integrative nationalism, and failure to appreciate the intelligence of the electorate and trust them – just to name a few.

The MCO period has seen Malaysians rise to the occasion as they always do in national crises – but in unprecedented ways. Civil servants in the Health Ministry and health professionals have performed exceptionally saving lives, deserving the international kudos they have received. The generosity by ordinary citizens to charities is in the millions – across faiths and races, to be distributed across faiths and races.

Professionals and experts have spoken out – even to face public censure as they bring attention to shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) and call for a greater reliance on facts and science. The public has repeatedly called the government out for policies shortcomings (and in some cases, nonsense) and offered ideas to consider, while praising those who have excelled.

There even have been controversial calls to support the government among traditional opposition supporters, as most Malaysians would like ‘politics’ – and the harmful practices destructive and dividing consequences it has perpetuated – to be put aside to focus on crisis management.

The dominant narrative is the cries to put the interests of people first - to protect those in harm’s way. For many, there has been greater public distancing away from all the political parties as many are fed up with how the political system is (not) working.

Despite distrust, Malaysians want their government to work. There is a reservoir of goodwill that can be tapped if Muhyiddin reaches out for different political lifelines.

A plural umbrella gov’t

A strategy that offers the most political strength for Malaysia in this crisis is a plural umbrella national government that includes more technocrats in areas of management, especially in the areas most needed, broad task forces to discuss responses and recovery across the political divide and inclusive of civil society, a parliamentary session that allows new ideas to be raised and constructive alternatives to be presented and greater representation in leadership.

Members of all major political parties could be invited to be part of it, as could talented professionals from the private sector. Special attention can be brought to bring in younger leaders, who offer new visions and have less personal baggage that constrain their ability to work with others.

While maintaining its legal constitutional framework – as other countries are doing – this arrangement could be tied to creating bodies operating under the National Security Council (NSC), which are accountable to both the executive and parliament. Separately, a watchdog body and parliament committee could be set up for oversight and inputs. An agreement for a clear fixed period of time to manage the crisis could be reached, based on the principle of putting Malaysia first and a working consensus.

The strongest form of legitimacy will come from the Malaysian people – who ultimately are the ones facing the multi-faceted crises the country (and the world) is facing. Malaysia’s strength has always been its diversity, and this collective talent is needed more than ever to assure that everyone is not left out. Reaching out for help is a sign of strength, not weakness. Voters will reward those who put them first.

So far, the four most important global lessons of success in effective political management of Covid-19 have been transparency, broad engagement, clarity and compassion in communication, and equitable application of the rules that put the community not individuals first. The same lessons could be applied to Malaysia’s political situation moving forward.

Many reading this will have dismissed the idea of a plural umbrella national government as unrealistic and too idealistic – and they are not wrong given trends as decisions have further constrained political options from the Sheraton Move onwards and past behaviour of many of the leading players across the political divides. They may also reject the idea of a party member working with an ‘enemy’ party.

History over the last decade in Malaysian politics has shown that new alliances and arrangements are however possible. Public calls for accountability are playing, and have played, a major role in reshaping relationships and pushing the country forward. Now when the country is locked down, the need to present viable openings is more pressing than ever.

Muhyiddin (still) has the opportunity in this crisis to improve his government’s response and restructure his government – to get himself out of lockdown. Individual sacrifices will reap rewards for the broader community – and in fact, when all is said and done, these may not be sacrifices at all if the decisions taken save lives and strengthen Malaysia(ns) for the challenges ahead.

BRIDGET WELSH is a Senior Research Associate at the Hu Feng Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies, a Senior Associate Fellow of The Habibie Centre, and a University Fellow of Charles Darwin University. She currently is an Honorary Research Associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia's Asia Research Institute (Unari) based in Kuala Lumpur. - Mkini

Lu pandei le cakap. Bukan tahu hati melayu.

ReplyDeleteBriget Welsh Well said.

ReplyDelete