My secondary school essays about Wawasan 2020 were packed with a whole load of nonsense.

Aged 15 in 1991, when then prime minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s plan for a developed Malaysia got hastily added to the syllabus just before exams, all I cared about was giving my teachers what they wanted - and end every essay with a couple of lines about how we needed to be united to become truly developed.

I can’t say I believed most of what I wrote. But if there was one thing I knew even back then, it was that Malaysians weren’t united. And we weren’t all equal.

My family wasn’t rolling in it. But neither were we poor. Both my parents were civil service clerks who owned a car and their own home. And in 1990s Malaysia, that meant we had enough for me not to qualify for free textbooks.

I had, however, many friends whose lives weren’t like mine. Did Dr M’s vision of a developed Malaysia mean they and their families would be taken care of? If it did, perhaps this was a vision worth working towards.

30 years on, unfortunately, reality paints a vastly different picture to the one many of us, perhaps even Mahathir himself, envisioned when Wawasan, or Vision, 2020 first entered the public lexicon.

Pass or fail

Yes, Covid-19 has indeed done a number on the country, resulting in a battered GDP and the worst unemployment figures in decades. Even so, it wasn’t exactly sunshine and roses before the pandemic, with one report in the months leading up to 2020 highlighting how poverty remained a way of life for a fifth of Malaysians.

That being the case, would it be fair to say the vision failed?

An Ipsos survey from 2019 revealed that 38 percent of Malaysians believed we hadn’t achieved the goal of becoming a developed nation. But while there is indeed merit to that view, perhaps, it’s not as simple as pass or fail.

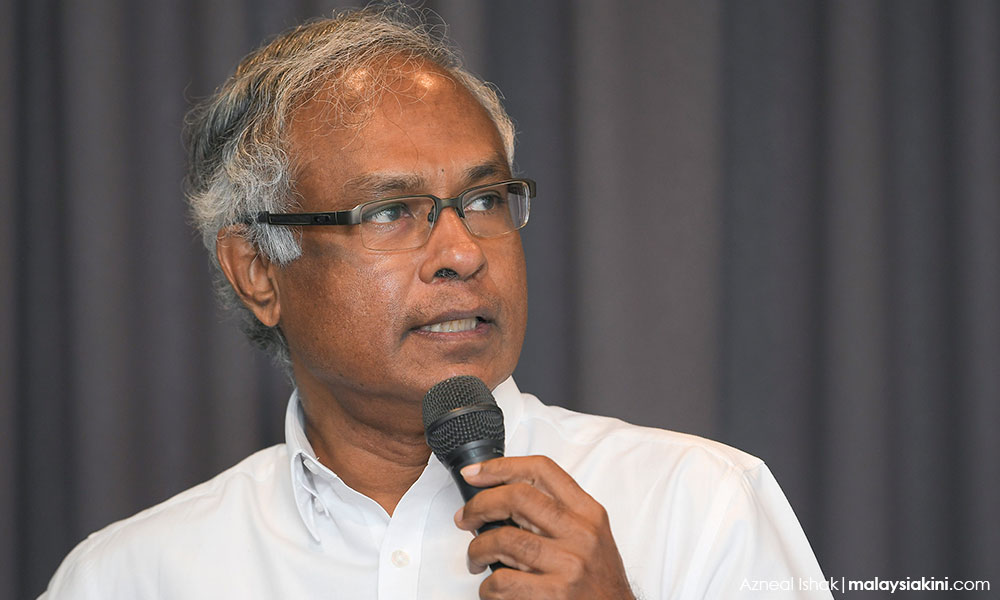

“I wouldn’t say we’ve failed completely,” Parti Sosialis Malaysia (PSM) chief Dr Michael Jeyakumar Devaraj told me.

“In terms of GDP growth, it’s quite good. If you compare us with some of the other Asian countries or countries in Africa, our GDP is 10 times higher. Perhaps we haven’t hit all the targets, but we’ve achieved a fair bit.

“Even in a recession year, shareholders of the top companies have seen their shares maintain at exactly the same pace. However, the ones who have really been hit are the poor. The daily-waged workers, people with small businesses, school bus owners, canteen operators... that’s kind of a reflection of how the last 20, 30 years have gone.”

It wasn’t supposed to be this way, said Jeyakumar, whose 2015 book, An Alternative Vision for Malaysia, details some of the socio-economic problems that have stood in the way of the march towards a developed nation status. No one was supposed to have been left behind.

Road to the future

Contrary to the collective memory of the Malaysian public, Mahathir’s vision of a developed nation by 2020, as articulated 30 years ago, aimed not just for economic excellence but holistic growth that would set a new standard for what developed people ought to look like socially, politically, spiritually and culturally.

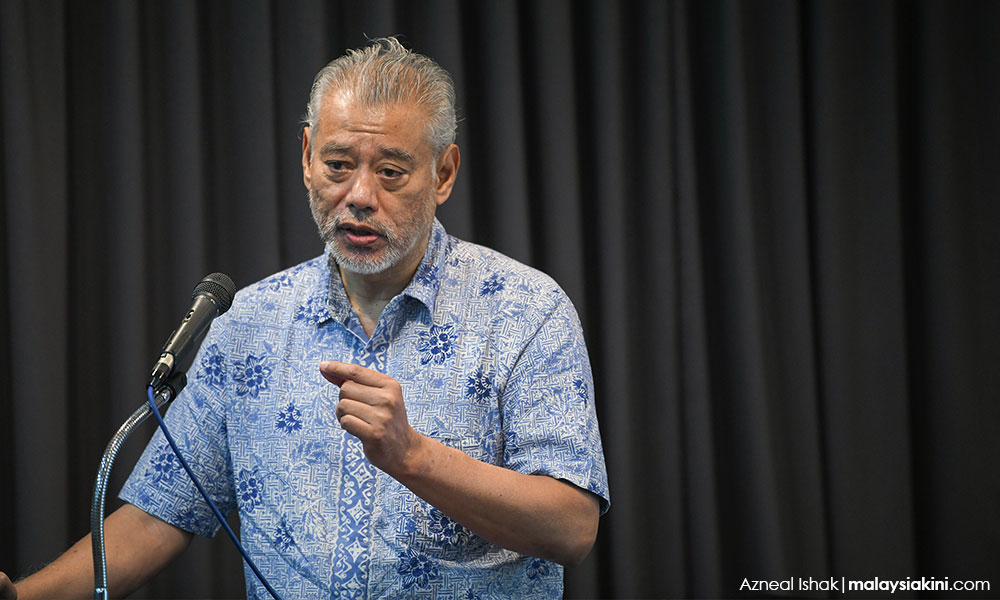

Renowned economist Jomo Kwame Sundaram, who’s often been outspoken about Malaysia’s class disparities during the Mahathir era and critical of the ex-PM’s policies, nevertheless, considered Wawasan 2020 to be Dr M’s finest moment.

Malaysia in the 1980s, he explained, was a nation gripped by much uncertainty.

Mahathir, having taken the helm from Hussein Onn in 1981, had looked to move the country towards industrialisation and emulating the economies of South Korea and Japan.

Unfortunately, not only would trouble hit his economic ambitions in the form of a recession, there’d be challenges — some of his own making — on the political front too.

This would lead to among other things, the deregistration and eventual reestablishment of his party Umno, the dramatic axing of the head of the judiciary as well as power plays like Ops Lalang, a major police crackdown which critics always claimed was more about stifling dissent than arresting racial unrest.

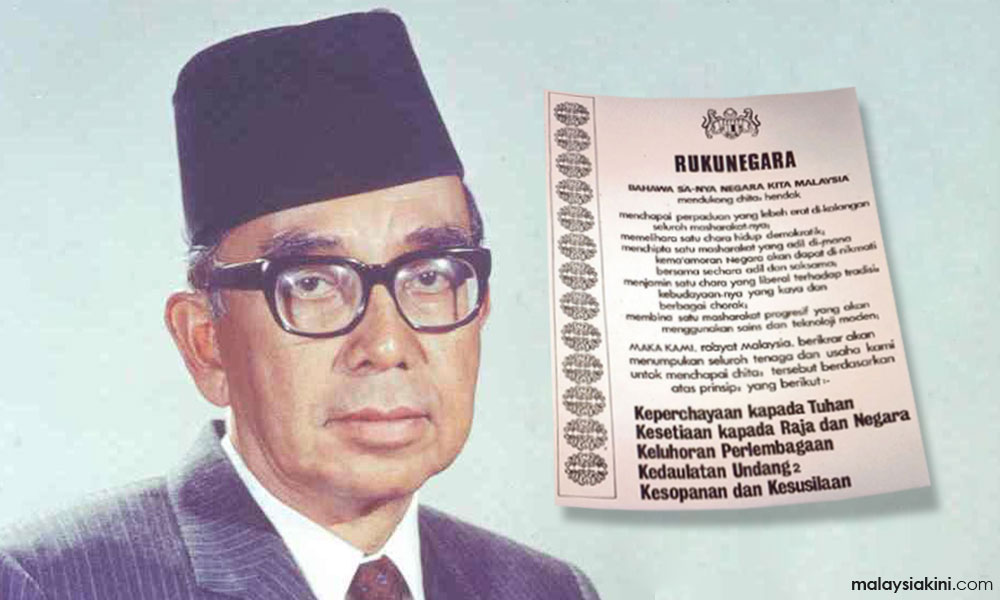

As the 1990s began, however, it was Mahathir who was front and centre calling for unity, seeking to reestablish the ideals set out in the Rukun Negara, the national policy introduced in 1970, recalibrate the racially divisive New Economic Policy (NEP), and map a path to the future.

“By 1990, the experience of the previous 20 years was such that rather than a means to achieve national unity, the NEP had come to be viewed as an end in itself,” Jomo said.

“This idea of Ketuanan Melayu (Malay dominance/supremacy) was also being espoused by Abdullah Ahmad, a former aide to Tun Razak (Abdul Razak Hussein, Malaysia’s second PM), who’d been detained under the Internal Security Act and was looking to make a political comeback.

“So when you look at Wawasan 2020, you see that what it attempts to address are the questions: What is this new Malaysian nation to be? What does it mean to have national unity? It talked about adopting a scientific approach. About being open-minded and liberal. It was a rejection not only of the past, but of what the past represented.”

Hamidin Abd Hamid, a historian at the University of Malaya who focuses on nationalism in one of the courses he teaches, added that the glue that held the plan in place was the aspiration towards a united Malaysian race.

“I’m not saying that after independence, we didn’t want to be united. But what Wawasan 2020 did was express the need for it. After Merdeka, we had this very laissez-faire system that eventually led to May 13 and the NEP being introduced.

(The bloody May 13, 1969 race riot was a racial clash between Malays and Chinese that led to the deaths of almost 200 people — though some historical accounts argue that almost 10 times as many perished.)

“With the NEP, we tried to eradicate poverty and reorganise society. But what kind of society were we? The idea of a tolerant and united Bangsa Malaysia (one Malaysian race) in Wawasan 2020 provided us with a blueprint,” Hamidin said.

It’s hard to know, of course, if everyday Malaysians on the nation’s 1990s mini buses knew or understood any of this.

But what is clear is that from the Independence Day slogans to specially-launched unit trusts and theme songs, both official and unofficial, on the radio, there was no escaping Wawasan 2020 and a sense that individually and collectively, we’d be in great shape come 2020.

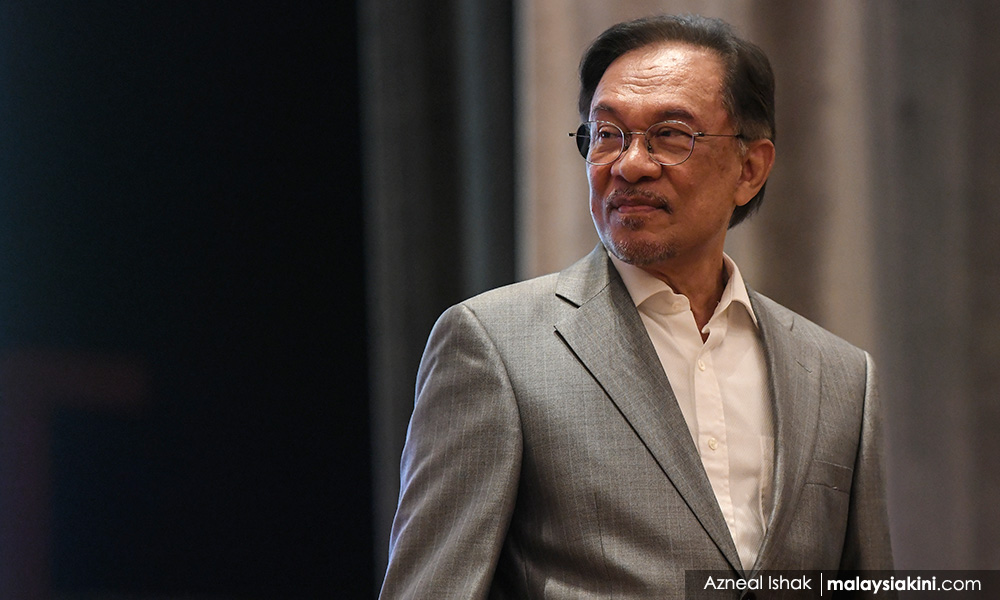

Yes, propaganda perhaps added much to the good feeling. However, the economy had also picked up by the 1990s, and the government at the time, led by the formidable tag-team of Dr M and his then-trusted right-hand man Anwar Ibrahim, appeared to be making all the right moves - economically, at least. And that led to major gains, politically, for the BN ruling coalition in the first election of the Wawasan era.

Crash, boom, bang

But then, as quickly as it had begun, everything came crashing down.

First, the Asian Financial Crisis hit. And in the middle of that, Mahathir’s deputy found himself out of a job and facing corruption and sodomy charges.

The plan had been a steady trek towards the holistic development of the Malaysian nation. But the events of 1997-1998, Jomo believed, threw everything off course.

“The pace of industrialisation slowed down a lot after that. Yes, industries continued to grow (after we recovered). But it was nothing compared to the decade leading up to the financial crisis,” he added.

Financial and political crises aside, however, perhaps, there were also inherent flaws in the Wawasan 2020 idea that ensured its failure.

The path to development, as put forth by Mahathir in his speech to the Malaysian Business Council on Feb 28, 1991, had mooted the meeting of nine aspirations. Yet, save the point on economic growth which the then PM said would entail a doubling of the GDP every 10 years, there was just too much ambiguity around the other aspirations.

How were we to become a liberal and tolerant society? How was a mature democratic society to be fostered given the tried and tested Malaysian political playbook of race-based political parties and race-baiting politicians? The strategies weren’t clear.

“Vision 2020 was based on this sense of genuine inclusion. But the policies did not follow that particular orientation,” political analyst Bridget Welsh, who specialises in Malaysian and Southeast Asian politics, told me.

“In fact, what we saw was the opposite in issues of race and religion. The framework never became part and parcel of the national ethos. And I think that was because of a lack of wanting to make these ideals real and (instead) to use other ideals for and to win political power.”

Zarina Nalla, who worked for many years in the areas of public policy strategy and consulting and co-founded the International Institute of Advanced Islamic Studies Malaysia, added that poor implementation also explains some aspects of the grand plan’s failure.

She said, “It’s not just Wawasan. So many national policies, including the NEP, have failed because of poor implementation. I know, not everybody embraces the NEP, but the NEP’s objective was to help raise the socio-economic status of the Malays. But that didn’t happen. The policy got corrupted and abused.

“So yes, we had this great policy, but there were flaws in the implementation processes which were apparent from previous policies, and we didn’t focus on addressing them. The result is we failed to bridge the gap between the haves and the have-nots. That’s the saddest thing for me.”

Hindsight is 20/20

In The Way Forward, the white paper Mahathir presented to the Malaysian Business Council in 1991, the then PM noted that for continued success, all the foundations for growth ought to be in place by 2020.

The paper read: “Most of us in this present council will not be there on the morning of Jan 1, 2020. Not many, I think. The great bulk of the work that must be done to ensure a fully developed country called Malaysia a generation from now will obviously be done by the leaders who follow us, by our children and grandchildren. But we should make sure we have done our duty in guiding them with regard to what we should work to become. And let us lay the secure foundations they must build upon.”

The reality, however, is that when Jan 1, 2020, rolled around, the world still considered us a developing economy. And while the inclusion of Malaysian billionaires on international rich lists may tell one story, the narrative here at home for about two decades now has been one of economic inequality.

Back in the days when Najib Razak was PM, the focus had been on pushing Malaysia towards high-income nation status. Not only did we not win on that front, poverty has continued to rise.

Additionally, for all that talk of a Bangsa Malaysia once upon a time, the only instances when true unity has been seen in recent years was when we were glued to our TV sets, cheering on sporting heroes like Lee Chong Wei.

So what went wrong? And who’s to blame?

Mahathir, the architect of Wawasan 2020, who’s seen not just his vision of a developed Malaysia dissipate but a second tenure as premier cut short following last year’s political coup, is positive — it’s all the fault of his successors, Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, known as Pak Lah, and Najib.

“We developed a policy, approach and strategy that had obviously contributed to Malaysia’s growth to the point where Malaysia became an Asian tiger. So obviously, if you had followed that line, you would continue to do well,” he said.

“But unfortunately, they saw in becoming prime minister opportunities for personal gain... they did things which were not really for the good of the country.”

Finding fault with his replacements isn’t something new for the 95-year-old ex-PM. In fact, since 2003, when he stepped down from his first tenure at the top, one could always count on snarky salvos being fired and/or brutal blog posts being penned upon new initiatives being announced.

Still, perhaps, on the subject of development paths his successors chose to take, Mahathir isn’t entirely wrong.

Both Pak Lah and Najib appeared to have markedly different ideas of what a developed Malaysia might look like and how to get there, which perhaps explains why during their tenures at the top, one tended to hear more about Islam Hadhari, human capital development, and New Economic Models than Wawasan.

And then, of course, there was Najib’s ostensible recalibration of the Wawsan 2020 plan that involved a push towards attaining high-income nation status, a rejig of the original vision that Mahathir was particularly dismissive about.

“After I stepped down… at one forum attended by a lot of business people, I told them that what we need to do is to have high income with high productivity. That productivity is very important. If you have high income and low productivity, you’re going to be in trouble. Unfortunately, when it came to Najib, he talked constantly about high income, but not about high productivity,” he said.

“You can give people more money, but if it produces less, you’re going to have a high cost of living… (I have said) don’t base it on per capita income, base it on purchasing power, on the so-called McDonald’s (Big Mac) index. I stressed this many times. But they wanted just to be popular.”

Jomo doesn’t entirely agree with Mahathir when I put the question back to him, maintaining that Wawasan 2020 was collateral damage in the aftermath of the Asian Financial Crisis and Anwar’s sacking, with Pak Lah and Najib contributing little to its demise.

“It may not have been intentional, but those events essentially caused the project to be abandoned and it was never really revisited.

“Najib’s New Economic Model was more or less what Mahathir did in the 1980s. He then became obsessed with living up to Mahathir’s idea of becoming a developed country, and what he basically did was to try to get to those targets, stats-wise, by not acknowledging the existence of foreign workers.

“When you remove about seven million foreign workers from your workforce, the denominator gets much smaller, and then it seems like we have reached the goals when we actually haven’t.

“It’s true that Mahathir was more committed to industrialisation than his successors and focused on productivity, but Wawasan 2020 itself, which went beyond commitment to modernisation and the idea of national unity, got abandoned before he left office.”

Mahathir, though, insists that while the events of 1997 had a big effect on the economy, Wawasan was still on the cards. On the topic of Anwar, however, the former premier vacillates somewhat and talks instead about his former deputy’s inability to win Malay backing.

The Malay dilemma - and the path forward

The line about the support of the Malay voter base being a prerequisite for political success in Malaysia is one of Mahathir’s oft-repeated lines since he and the former Pakatan Harapan government’s tenure was cut short. What’s odd, though, is that the ex-PM is the same person who’d championed the establishment of a united Malaysian race three decades earlier.

“I had hoped that when we talk about Bangsa Malaysia, it would be a bangsa with one common language, one culture. (Though) the religions may be different,” he remarked. But that was always going to be a challenge, he added, because the leaders of the different races have always preferred to play up “the forces that push us apart”.

Despite noting this, however, Mahathir maintains the need for race-based politics.

He added too, when I asked about liberalism having become a bad word, that despite a liberal approach to Malaysian life being listed among Wawasan’s nine aspirations and promised by the Rukun Negara, aspirations differ greatly from reality.

“(Liberalism is) the aspiration of the educated few, the sophisticated few, the people who have travelled abroad and studied abroad. When they come back, of course, they have a different perception of things.

“But the people who are in the country, who practically never left the country, they have a different viewpoint. They are not liberal at all, they worry about themselves… that’s why things are this way until you can break the disparity.”

The disparity between the haves and have-nots, Mahathir added, remains pronounced along racial lines. This is why affirmative action policies are still necessary.

Welsh is critical of this view, noting that it is not necessary to address one thing (in this case, class disparity) before dealing with other issues like liberalism and unity.

“It’s a very post-colonial approach that does not capture the way the rest of the world has dealt with issues of modernity,” she said.

On the question of race-based politics, meanwhile, Welsh noted that while there is certainly a need for different forms of mobilisation, Malaysia must move beyond race in order to formulate policies that will drive the country forward.

“The class divide needs to be addressed. And you have to address the ideological foundations concerning the way people think. For example, among the Malay community itself, there are people who think very differently from each other. Race-based politics, however, tends to view them all as one unit. That is disrespectful to the community.”

And what of affirmative action? Is there a place for it in modern Malaysia?

PSM’s Jeyakumar believes there is, and added that non-Malays are sometimes unaware and unempathetic of the issues faced by the poor.

“The tendency for non-Malays is to rubbish affirmative action. But that’s a very chauvinistic viewpoint. Many affirmative action policies the government introduced were good. The mistake was that these policies were blind to the non-Malay poor. That doesn’t, however, cancel out the good work.

“So what should be looked at going forward is how we can maintain these initiatives, ensure they’re not being hijacked by the Malay rich, and bring the non-Malay poor into the fold.”

Wawasan 2.0

Launched during Dr M’s second stint at the top, Shared Prosperity Vision 2030 (SPV 2030) which effectively postponed the 2020 target date by 10 years, had focused on evenly distributing wealth and addressing societal imbalances. And according to Mahathir, strategies were being put in place to ensure everyone was guaranteed a slice of the piece.

“In (Harapan), we worked out a system and an approach which would enable even the rural people to become fairly well off. Not rich, but fairly well off.”

Unfortunately, the ex-premier added, his government got booted out.

Jomo is not convinced by the argument, however, noting that Pakatan had the opportunity to push through reforms during their 22 months in power but didn’t.

Welsh agreed too that it might be premature to assume the former government could have tackled issues related to the wealth gap when SPV 2030 hadn’t been properly laid out. She did note, however, that Pakatan appeared to be moving towards a more positive way in which to address issues of socio-economic inequality.

Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin, although no longer part of the coalition which launched SPV 2030, has since said he’s committed to seeing his former partners’ new development plan through. But questions on the legitimacy of the current administration aside, one thing to be asked is whether a turnaround of fortunes is achievable in just nine short years.

Mahathir smiles, though it’s clear there’s no love lost between the former political allies-turned-enemies.

“It is easy to draw up a policy. It is also easy to adopt a policy. But implementing a policy requires different skills.

“Many of the things done during my time were common things. Like building a bridge to Penang, like building a highway. Those were common ideas… but if you don't know how, you cannot (do these things).

“How do you reduce the disparity between town and country? He (Muhyiddin) does not know how to implement. Yes, he has done the right moves. But right moves alone doesn’t achieve much,” he said of his former ally.

That being the case then, can the ideals of Wawasan ever be attained?

“I believe that if we can reduce the disparity between the races, we can achieve a much more united nation, where people would be proud to be Malaysian. Not Malaysian Chinese, Malaysian Indian, but proud to be Malaysian. But at this moment, we are not doing that. We are not achieving the objectives. So it will take a long time,” he said.

The question, of course, is: how long is a long time? And can Malaysia afford to wait?

This article was originally published on BETWEEN THE LINES, a weekday newsletter that curates the most important news stories of the day and explains the context behind them. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.