A former stately home in Penang reminds Alan Teh Leam Seng of Perak's rich tin mining heritage and its relation to the nation's largest and longest-running smelting concern that began 125 years ago

A MORNING walk in George Town eventually leads to Jalan Dato Keramat, a main thoroughfare that connects the city centre to Air Itam.

Owing its name to a shrine, said to be located in the vicinity of nearby Kampung Makam, Jalan Dato Keramat boasts many attractions, including century-old mosques as well as Indian and Chinese temples, pre-war heritage buildings with intricate facades and countless eateries serving a plethora of culinary delights that make Penang famous the world over.

With noon fast approaching, the air-conditioned interior of the imposing Birch House comes as a welcome respite from the tropical heat.

Although home to an international fast food restaurant chain today, the well conserved landmark still exudes an exciting old-world charm and effortlessly brings to mind its key role played as the headquarters of the former Eastern Smelting Company, or Escoy.

RICHEST TIN DEPOSIT IN THE WORLD

Despite enjoying an enviable reputation as a world-renowned Penang-based tin-smelting plant during its heyday, Escoy almost exclusively processed tin that came from Perak's Kinta Valley, then the richest place in the world in terms of tin ore.

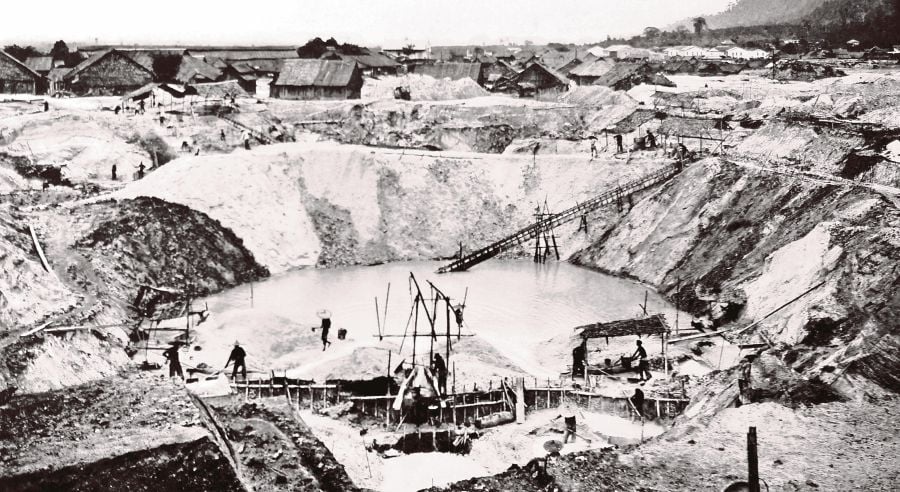

Abundance was not an overstatement as 19th-century surveys revealed that practically all the 2,000 square kilometres of land surrounding Ipoh town contained deposits in varying amounts and depth.

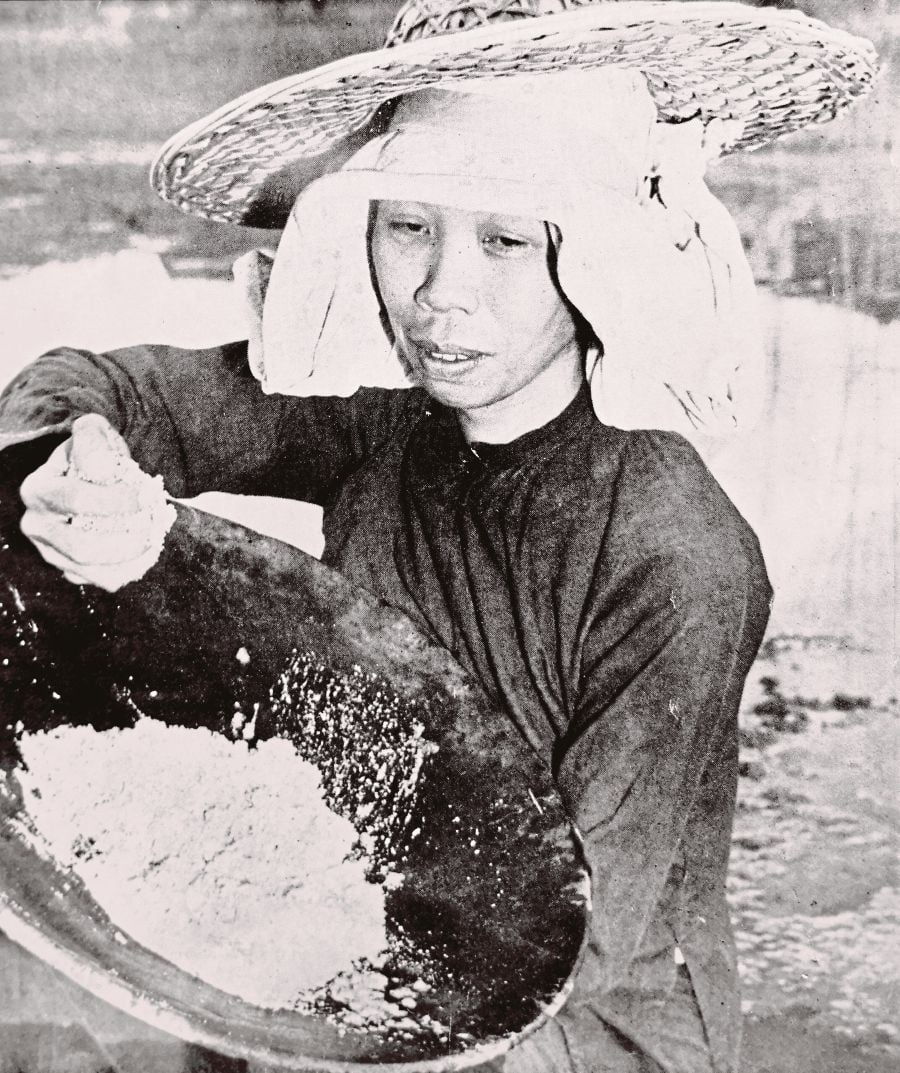

Although identities of the first Kinta Valley tin miners have been lost to the sands of time, historians believe that Malays were pioneers based on the discovery of 16th-century tin coins during excavations. Historical evidence also proved that dulang and palong were two Malay-inspired techniques that survived the test of time and were still popular in the 20th century.

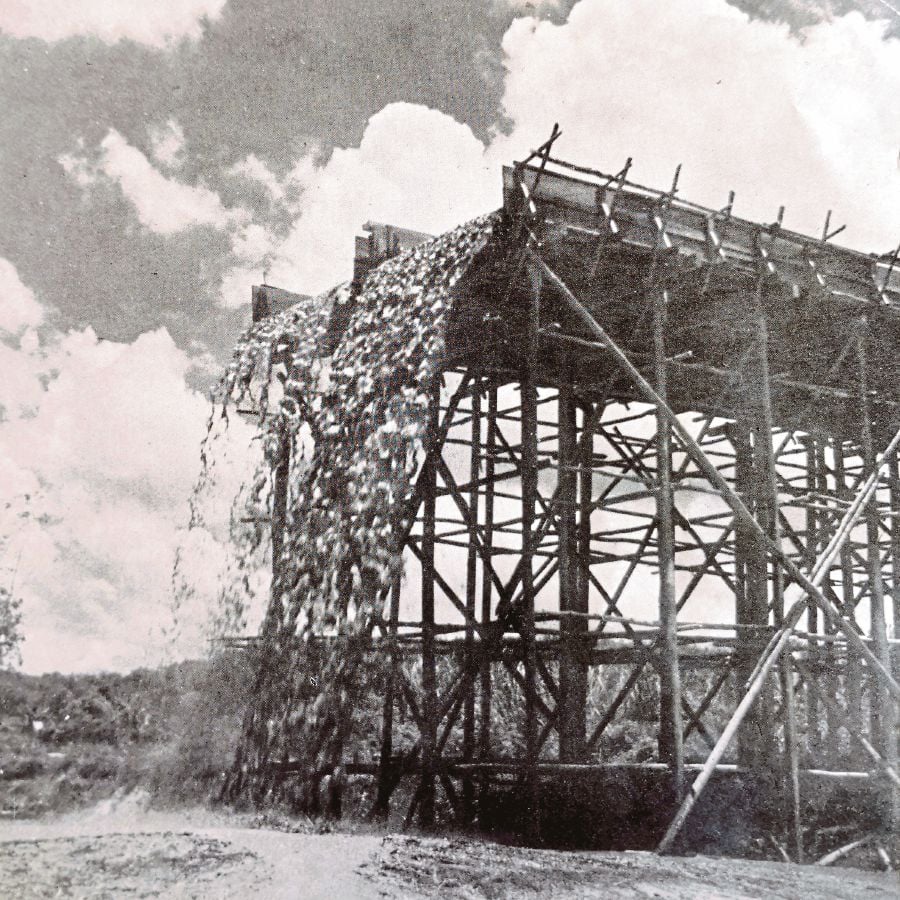

The former involved the use of flat wooden pans to obtain tin ore from river beds and flood pools while the latter came in the form of raised wooden structures that separated the prized ore from sand and soil sediments.

Next in line were the Siamese, whose Lombong Siam took the form of shallow rudimentary pits.

The lack of flood-prevention knowledge deterred them from digging deeper and were, consequently, forced to leave more extensive and richer deposits located below the water table untouched.

This obstacle was eventually surmounted by the Chinese, who began mining in the 19th century by adapting wooden chain pumps, used to irrigate padi fields back home in China, to great effect when working abandoned Lombong Siam. Apart from reaching greater depths, they replicated techniques used back in Yunnan and Guangxi provinces by driving man-size shafts along the rich veins to extract tin ore efficiently.

Apart from introducing the cangkul or hoe, Chinese miners were also quick to improve the Malay palong function by affixing wooden strips to trap denser tin deposits as gravity moved the material downwards. Despite its technological superiority, the chain pump was, however, still not powerful enough for miners to reach greater depths where the richest veins were waiting.

EFFICIENT EUROPEAN TECHNOLOGY

Tin mining reached its full potential only in the late 1880s, some two decades after the Pangkor Treaty was signed to pave the way for British intervention in the Malay states. Interestingly though, the French, represented by engineer-explorers Jacques de Morgan, John Errington de la Croix and Xavier Brau de Saint-Pol Lias, were the first Europeans to visit Kinta Valley.

Apart from stating that annual output at that time was around 14,000 piculs, their comprehensive 1881 report revealed that there were sufficient tin deposits to sustain 25,000 Chinese miners employed for 100 years.

This mouthwatering revelation quickly led to the establishment of the first European tin mining concern in the Kinta Valley after de la Croix incorporated Société des Mines d'Etain de Pérak in Paris to exploit a mining concession in Lahat.

Other European companies followed in quick succession, bringing with them state-of-the-art equipment and novel mining techniques.

Among these were the steam-driven pump, which received wide acclaim and boosted profits tremendously when first installed in Taiping, and the innovative hydraulic mining methods.

With extraction intricacies finally dispensed, miners began finding ways to get the fruits of their labour to smelters in the cheapest and fastest method possible.

This was because nature, although generous in depositing so much tin ore in such a relatively small area, guarded the treasure jealously with steep mountain ranges in the north and impenetrable swamps and dense forests in the south.

During the early days, tin mining areas remained close to the river that gave the valley its name as the waterway proved to be the only means of transportation.

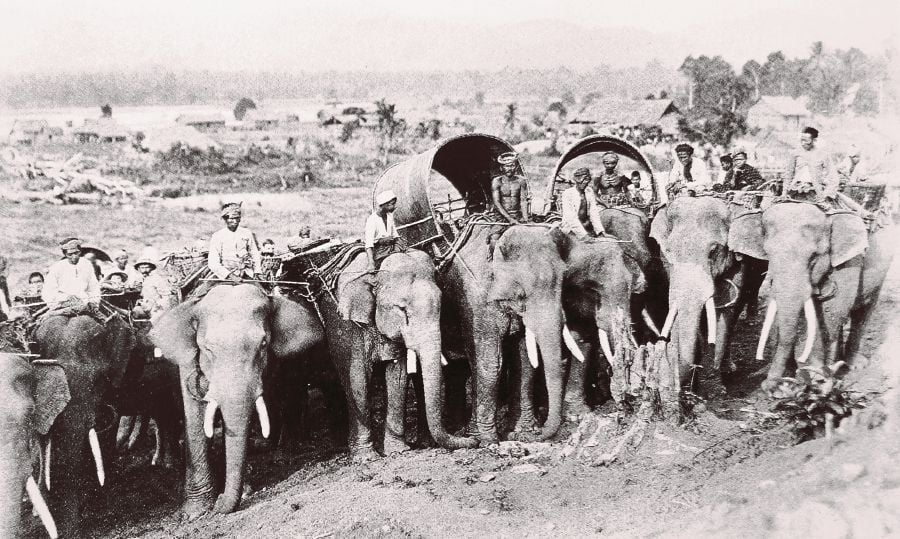

Boats, however, were soon replaced by elephants as intrepid miners began moving further inland in search of richer tin fields.

This improved form of transportation helped boost production significantly, causing it to surpass the 100,000-picul mark by 1888, and at the same time, gaining Malaya the enviable title of world's largest tin supplier.

These beasts of burden proved their worth most when moving large amounts of ore from the then newly opened Lahat-Papan district mines to the nearest river.

While establishing a depot to store the mineral before transhipment, the miners were said to have named the new river port as Batu Gajah to honour their pachyderm friends, and at the same time, hoped that the place would perpetually remain rock solid in terms of function.

RAILROAD TRANSFORMATION

Crude roads eventually replaced the lumbering elephant tracks and by 1890, every important mining area was linked by road to strategic ports along Sungai Kinta.

By then, the government had realised that tin was key to Perak's rapid development and a good communication system was needed to sustain this phenomenal growth.

Ipoh benefited greatly from this policy thanks to its strategic location right in the heart of the Kinta Valley.

By 1895, it had grown from an obscure village into a bustling town with rail link to the key coastal port of Teluk Anson (today Teluk Intan). Over the next eight years, annual tin ore production tripled to reach 319,000 piculs after all major towns and mining areas in Perak were connected by railway to Kuala Lumpur and Seremban in the south, and more importantly, northwards to tin smelters in Penang.

The looming brown and white towers of Penang Times Square come into sight after casting eyes through a nearby window. Built on land that was formerly home to Escoy's furnaces as well as machinery and storage depots, this valuable piece of real estate bears testimony to the amazing success experienced at the dawn of the 20th century.

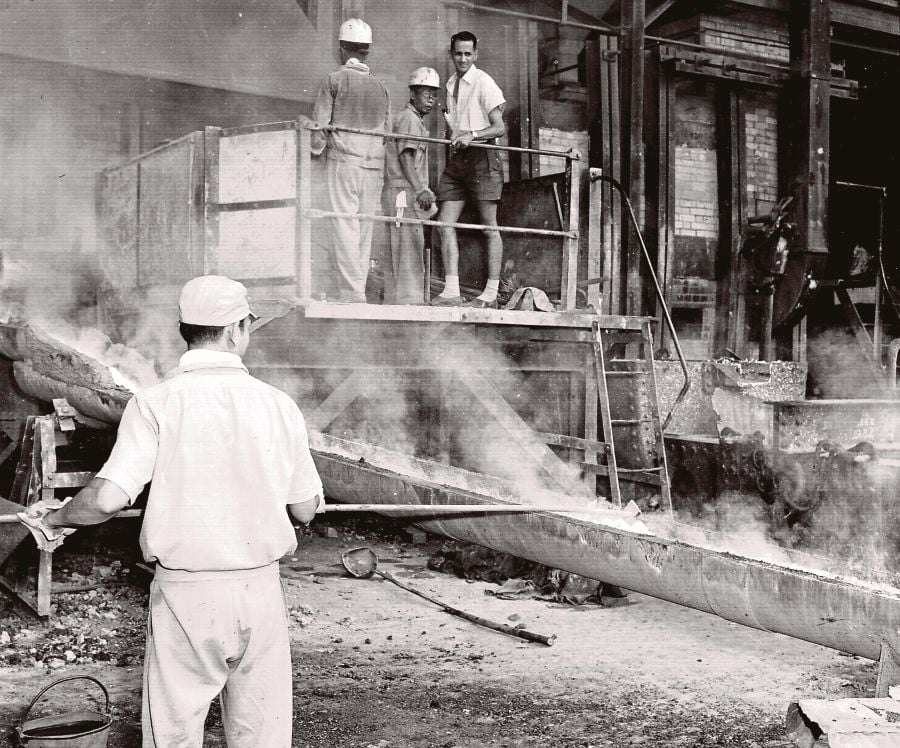

The windfall, however, did not happen overnight. Kinta Valley Malay and Chinese miners were already experimenting with smelting methods long before European arrival. Unfortunately, their inefficient low-temperature furnaces led to elevated cost overruns and severe wastage.

Observing this during a visit in 1885, German entrepreneur Herman Muhlinghaus capitalised on what he saw as a great business opportunity by teaming up with Singapore-based Scotsman James Sword to establish a coal-fired smelter in Teluk Anson. Unfortunately, smelting inefficiency once again proved to be a stumbling block.

Although Sword and Muhlinghaus went on to establish another smelter at an unused dry dock on Pulau Brani, near what is Keppel Harbour today, the sheer distance needed to travel all the way down to Singapore discouraged most Perak tin miners and prompted them to look towards Penang instead.

TIN SMELTING TYCOON

The humble beginnings of Escoy can be traced back to exactly 125 years ago when the scion of a wealthy tin mining family established Seng Kee Tin Smelting Works (SKTSW) in 1897.

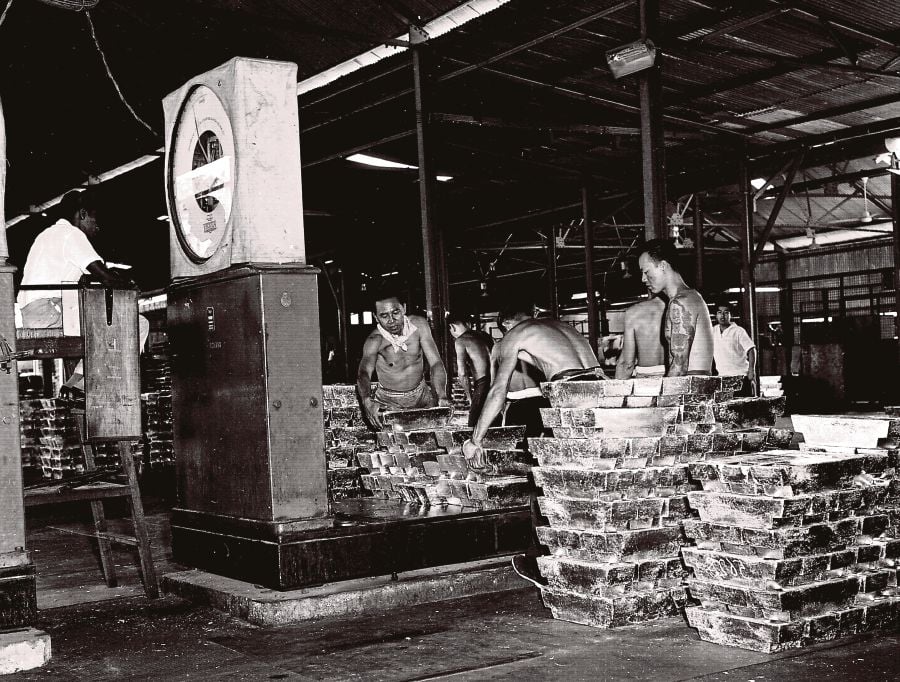

Learning from experience, Lee Chin Ho avoided mistakes made by early entrepreneurs and got off on the right foot by becoming the first Chinese smelter to use the efficient European-made reverberatory furnaces.

Comprising a mixture of buildings with the largest made of bricks with ceramic roof tiles and an imposing chimney while the rest were rudimentary attap structures, SKTSW began processing raw tin brought in from Kinta Valley and southern Thailand. Business prospered and Lee became one of the richest men in Penang.

Apart from giving back to society by supporting numerous charitable organisations, Lee extended his influence by serving on influential boards and trustees, including the Chinese Town Hall, Chung Hwa Confucian School, Penang/Georgetown Municipal Office, Rubber Trading Association and Chinese Recreation Club.

During his lifetime, he was also the Penang Buddhist Association president and Penang Chinese Chamber of Commerce vice-president.

In 1908, he decided to build a grand stately mansion as a symbol of his immense wealth and success. Apart from locating it beside the road for greater visibility, Lee was said to have placed a small Tang dynasty figurine of a general on the roof to harmoniously balance energy emanating from the Nagarathar Sivan Hindu Temple located across the road.

When completed, the double- storey bungalow became home to Lee's many wives, concubines and children.

In the early 1910s, Malaya's tin mining fraternity was overwhelmed by excitement after news broke that the Malayan Tin Dredging Ltd, a London incorporated company, had for the first time in history, recovered alluvial tin deposits from the depths of Batu Gajah swamps with a bucket dredge.

A shrewd businessman, Lee was quick to realise that the mechanical behemoth was the final missing link needed to unlock the unreachable immense tin reserves located within the depths of Kinta Valley's extensive and deep central and southwestern swamplands. Their deployment in significant numbers would surely result in huge amounts of tin ore arriving at SKTSW's doorstep.

LONGEST RUNNING AND LARGEST SMELTER

He set about expanding his business, but much to his consternation, discovered that even his wealth proved insufficient.

Acting on the advice of close friend and former Perak British Resident Ernest Woodford Birch, Lee sold the controlling stake of his smelting operation to the British. The company then became known as the Eastern Smelting Co Ltd with Birch acting as first chairman.

As part of the arrangement, the family was allowed to continue living in the house, subsequently renamed Birch House, until Lee passed away in the late 1930s. After that, it was turned into offices for administrative staff members.

On the way back, a quick walk around Penang Times Square's open space, aptly named Chin Ho Plaza, helps refresh memory that the smelting business was consolidated into Tin Smelters Ltd in 1929, and just over a decade later, the site was overrun by the Japanese after Penang fell on Dec 19, 1941.

Birch House, which was damaged during the Japanese Occupation, was renovated and refurbished after World War 2 ended. At around the same time, refined tin ingot production restarted after the place was taken over by British-owned Amalgamated Metal Corporation.

Two more corporate readjustments happened over the years before the furnaces were finally shut down for good in 1998, bringing both Malaya and Malaysia's longest-running and largest tin smelting concern to an end. - NST

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.