I refer to Bridget Welsh’s preliminary analysis of voting patterns among the major ethnic communities in Peninsular Malaysia published on Nov 25.

Her analysis of a divided electorate by ethnicity is largely correct with Perikatan Nasional (PN) winning a majority of Malay support, Pakatan Harapan winning a significant percentage of Chinese and Indian support and BN winning about one-third of the Malay support in Peninsular Malaysia.

My analysis here is to provide a greater understanding of voting patterns at the state and constituency levels in the peninsula.

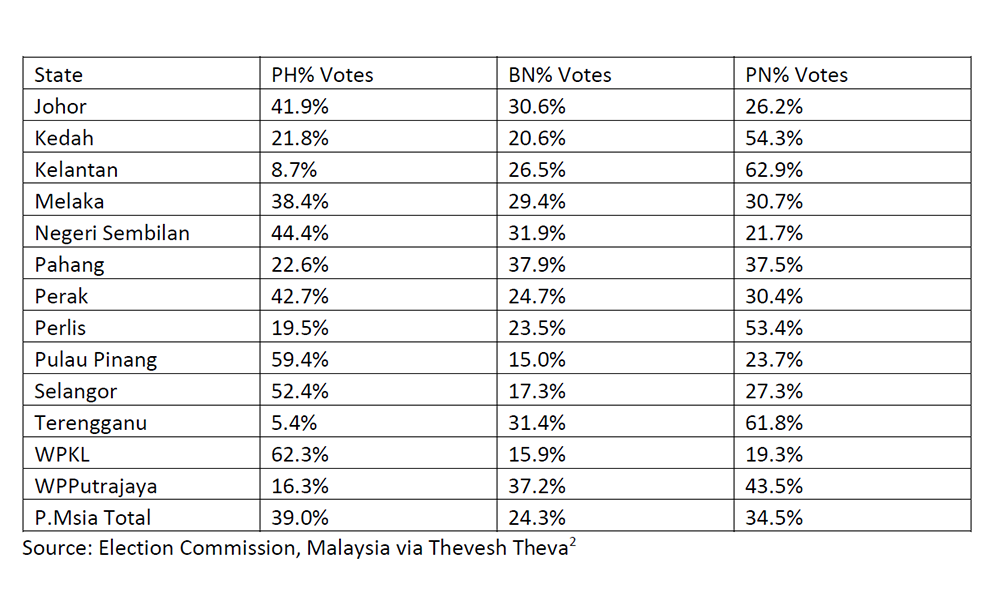

For example, the Harapan support of approximately 11 percent estimated by Welsh among the Malay voters in Peninsular Malaysia is no doubt affected by the low percentage of votes obtained by Harapan in Malay dominant states like Terengganu (5.4 percent) and Kelantan (8.7 percent).

Harapan’s Malay support would be higher than 11 percent in states where it is the incumbent state government - Selangor (52.4 percent), Penang (59.4 percent) and Negeri Sembilan (44.4 percent). (See Table 1 below)

Granular analysis

More accurate ethnic voting patterns can be obtained through a more granular and detailed analysis of the election results at the saluran or polling stream level for each constituency.

Such analysis will show much greater variation in ethnic voting patterns between and even within constituencies. This kind of granular analysis will also provide greater nuance and explanatory power to better understand voting behaviour in the Malaysian context.

I am starting with the parliamentary constituency of Bangi because of the ethnic diversity of my previous parliamentary constituency (51.5 percent Malay, 37 percent Chinese, 10.8 percent Indian and 0.7 percent others) and because I have access to the GE15 and GE14 polling stream and electoral roll data.

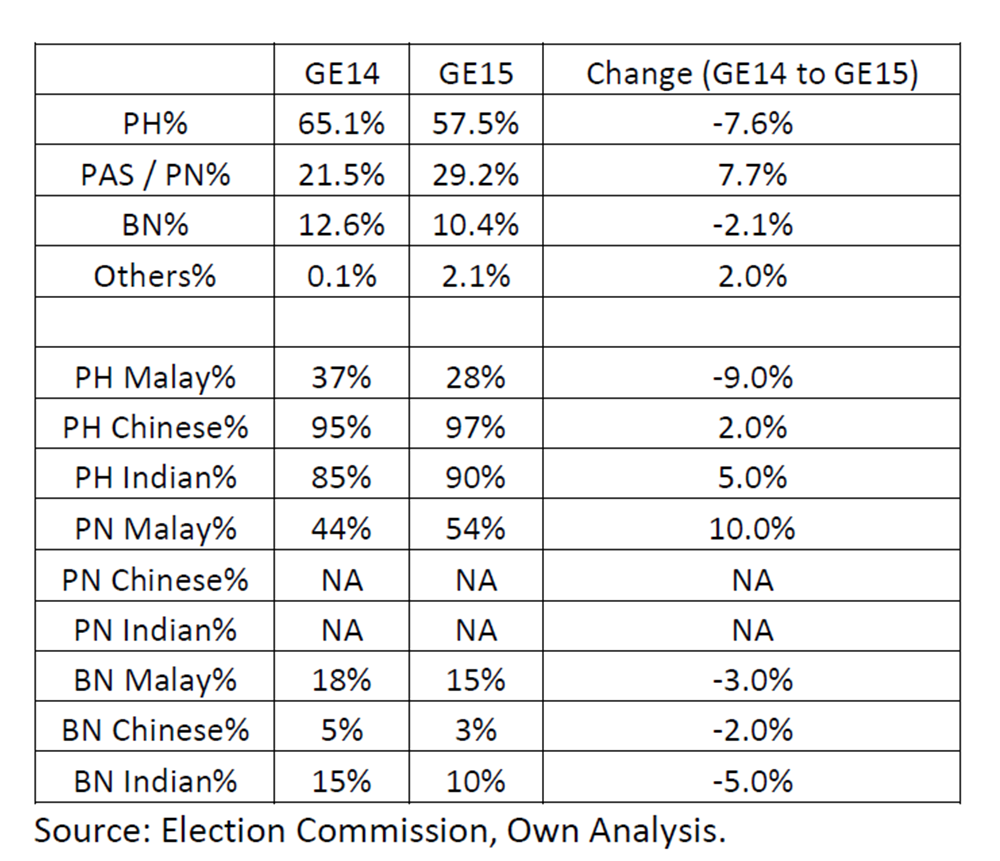

Bangi can be considered a relatively safe seat for Harapan. It won this seat with 65.1 percent of the popular vote in GE14 (with a majority of almost 69,000).

In GE15, Harapan retained this seat with 57.5 percent of the popular vote (with a majority of almost 70,000). PAS increased its share of the popular vote by 7.7 percent from 21.5 percent in GE14 to 29.2 percent in GE15 while BN’s share of the popular vote dropped by 2.1 percent from 12.6 percent to 10.4 percent.

Using regression analysis of the saluran data, I was able to estimate the Malay, Chinese and Indian support for Harapan, PAS/PN and BN in GE14 and GE15.

Malay support

The Malay support for Harapan fell from 37 percent in GE14 to 28 percent in GE15, a 9 percent drop. This is less than the 14 percent drop in Malay support estimated by Welsh for Harapan at the national level.

At the same time, the Malay support for BN fell from 18 percent in GE14 to 15 percent in GE15. PAS/PN increased its share of Malay support from 44 percent in GE14 to 54 percent in GE15, a 10 percent increase. PAS/PN gained Malay support from both Harapan as well as BN.

But because PAS/PN had negligible (ie almost zero) support from the Chinese and Indian voters, it could not pose a credible threat to win this seat from Harapan especially since Harapan won an overwhelming share of the support from the Chinese (97 percent) and Indian (90 percent) voters in this seat. (See Table 2 below)

The challenge for Harapan is to win close to 30 percent of the Malay support and 90 percent or more of the non-Malay support as a baseline. Then, Harapan will be able to win seats that comprise up to 70 percent of Malay voters, especially in a multi-cornered contest.

Harapan must be competitive among the Malay voters to win seats which have more than 60 percent of Malay voters. This is how Harapan managed to win seats like Kuala Selangor (69 percent Malay), Gombak (78 percent), Sungai Buloh (69 percent) and Shah Alam (75 percent).

Despite losing 9 percent support among the Malay voters from GE14 to GE15 in Bangi, Harapan managed to stay competitive in many of the Malay majority polling districts, including among the younger voters. This can be seen by examining the results by polling stream in some of these polling districts.

Polling stream outcomes

For example, in the Saujana Impian polling district – a middle-class 83 percent Malay majority area under the Kajang state seat – Harapan won more votes than PN (46 percent versus 39 percent).

PN won saluran two to four but Harapan won saluran five to nine, although the winning margin narrowed in saluran eight and nine, the two youngest saluran. (Chart 1 below)

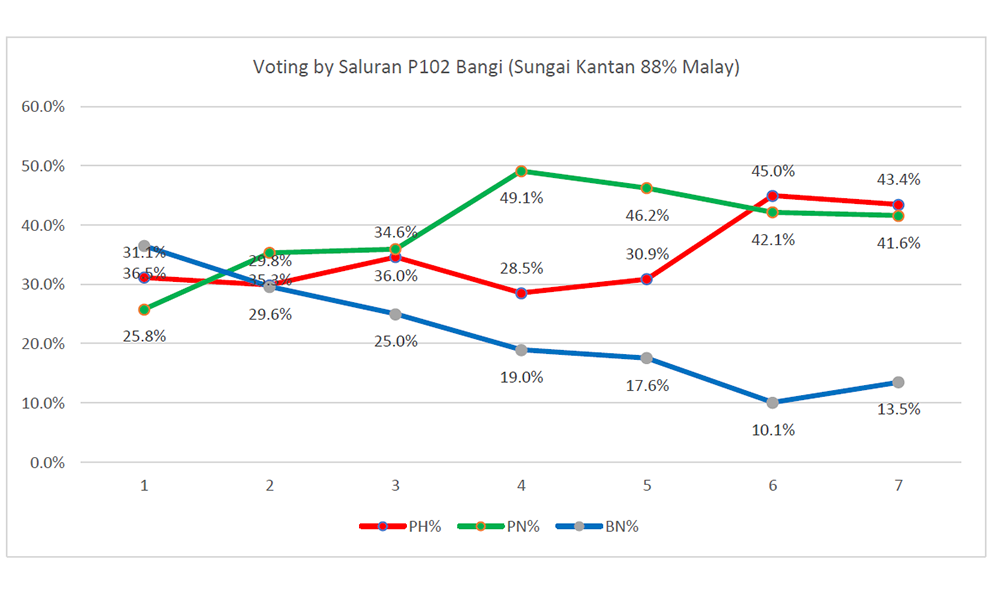

In the Sungai Kantan polling district (88 percent Malay voters), in a less affluent area under the Kajang state seat, PN outpolled Harapan by only a small margin (40 percent to 35 percent) and Harapan won a greater share of votes than PN among the younger voters in saluran six and seven. (See Chart 2 below)

Harapan fared less well in the Malay majority polling districts under the Sungai Ramal state seat which is situated in the Bandar Baru Bangi area which was a state seat formerly held by PAS for three terms (1999, 2008 and 2013).

But even in these polling districts, Harapan came in a respectable second and was the clear alternative to PAS among the younger voters, displacing BN.

For example, in the Sungai Ramal Dalam polling district (98 percent Malay), PN won 55 percent of the popular vote compared to 26 percent for Harapan and 17 percent for BN.

But Harapan narrowed the gap with PN among voters in saluran four to six and won more votes than BN in saluran three to seven. Even in youngest saluran seven which went to PAS with 61 percent of the popular vote, Harapan still managed to win 28 percent of the popular vote. (Chart 3 below)

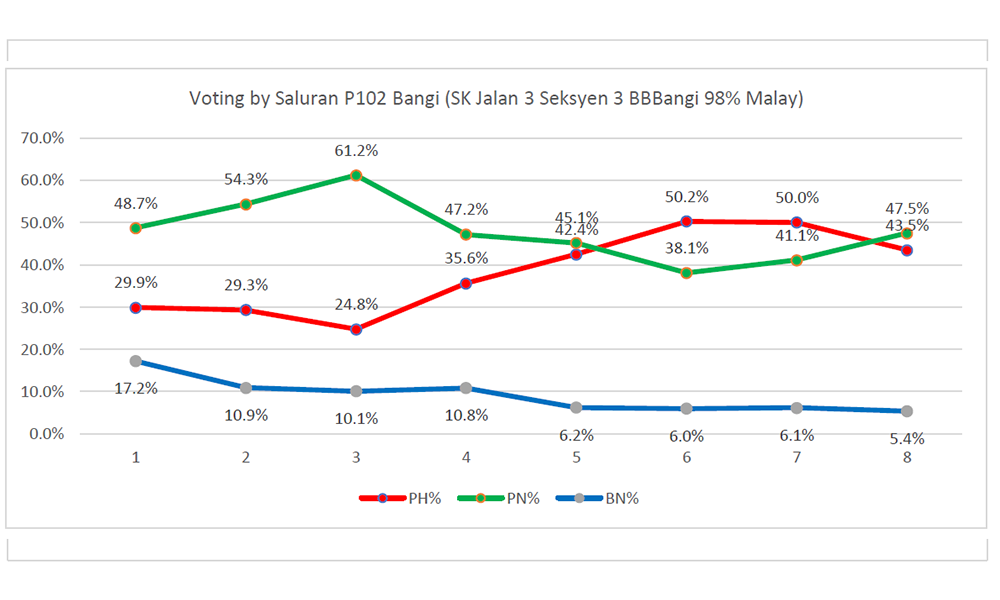

In the 98 percent Malay middle-class neighbourhood of Seksyen 3 Bandar Baru Bangi, Harapan managed to narrow the gap by winning 39 percent of the popular vote compared to the 48 percent won by PN.

Harapan was competitive in the younger saluran and even won saluran six and seven and only narrowly lost saluran eight, the youngest saluran by 4 percent (43.5 percent compared to 47.5 percent). (See Chart 4 below)

Harapan fared better in the Malay majority polling districts in the Balakong state seat where PAS and PN’s grassroots presence is not as strong as in Sungai Ramal.

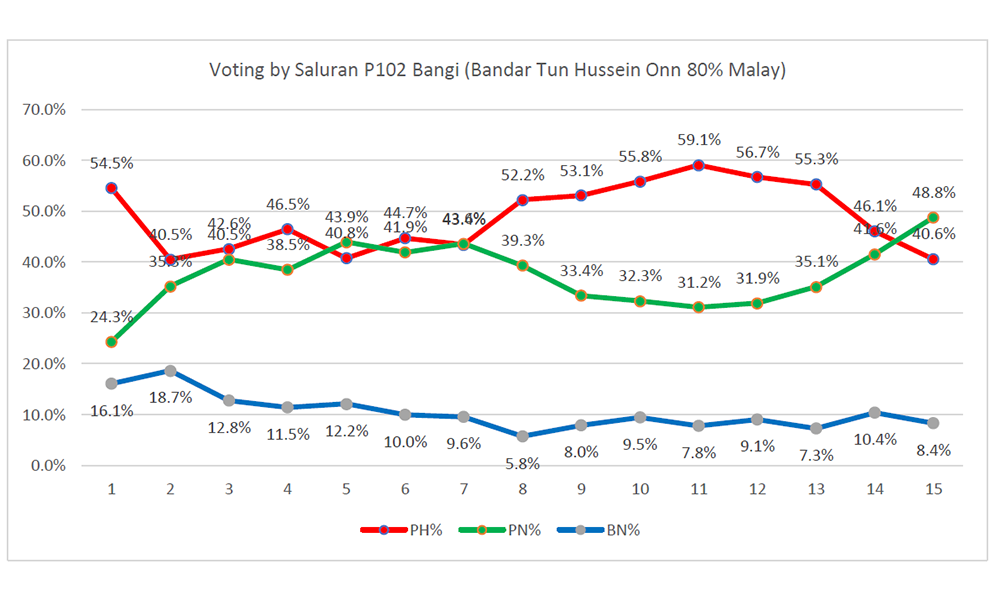

For example, in the Malay middle-class neighbour of Bandar Tun Hussein Onn (80 percent Malay), Harapan won a greater share of the popular vote (49 percent) compared to PAS/PN (38 percent).

Harapan had a clear lead over PN in saluran eight to 13 but PN fared better in the youngest saluran 15 winning 48.8 percent of the popular vote compared to 40.6 percent won by Harapan. (Chart 5 below)

In the less affluent polling district of Desa Baiduri (68 percent Malay), Harapan won 42.9 percent of the popular vote, just slightly ahead of PN with 42.1 percent and BN in third place with 13.5 percent.

Harapan won the earlier saluran from one to five (which have more non-Malay voters) but lost out or was even with PN in the younger saluran (from seven to 13). (Chart 6 below)

A few observations can be made from the saluran analysis of the Malay majority polling districts in Bangi that is shown above:

PAS/PN does better in polling districts/areas where they have had electoral representation in the past and hence, better grassroots. (This partly explains why Dr Halimah Ali, formerly a PAS assemblyperson and Selangor exco member, and Sijangkang assemblyperson Ahmad Yunus Hairi who is also a former Selangor exco member, managed to win the parliamentary constituencies of Kapar and Kuala Langat in Selangor.)

There is a noticeable increase in the support for PAS/PN in the youngest saluran in Malay majority polling stations. At the same time, Harapan is the clear alternative to PN among the middle age and younger Malay voters in the urban areas by beating out BN.

It is possible for Harapan to be competitive and even win more votes than PAS/PN in Malay majority polling districts. Local machinery and local servicing are important, especially in the less affluent areas where the personal touch of a candidate and his/her team can make a difference.

Similar granular analysis needs to be carried out in different ethnically mixed seats, using polling streams and polling district data to allow for a better understanding of voting patterns including the influence of factors beyond race such as class, age, grassroots strength of the various parties and constituency servicing by the elected representatives.

This can be supplemented with survey data at the constituency, state, and national levels, where available.

There is much variation in the support for the various coalitions at the state and local levels that need to be properly analysed and understood among the members of the media, academia, politicians and the larger public. - Mkini

ONG KIAN MING is former DAP MP for Bangi and a former deputy minister of international trade and industry.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.