The decision for Muda to go on its own and end its alliance with Pakatan Harapan has reverberated in national politics. From “good riddance” to well wishes, the sentiments (especially on social media) have been emotive and colourful.

Interestingly, this break-up has garnered even more social media attention compared with other recent political break-ups, from the ending of Pakatan Rakyat in 2015 to the split between PAS in Umno in 2021.

An uncomfortable alliance

The writing for separation between Muda and Harapan was on the wall since the Johor 2022 state election, before they even joined forces electorally. Harapan, especially PKR, was uncomfortable with another party that aimed to win over a similar multiethnic, pro-reform, progressive base of supporters.

While Muda made a good-faith effort to cooperate with Harapan in GE15 (and vice versa), the relationship was never one of equal acceptance. Even when they were allies, many Harapan-linked cyber trolls opted to focus their attacks (often highly personalised) on Muda rather than the Perikatan Nasional (PN) opposition.

In GE15, Muda was placed last in line for seats, negotiating for constituencies that no one else really wanted and allocated seats so close to polling day that the party was placed at an even greater disadvantage.

Despite claims to the contrary, its performance in GE15 was nevertheless on par with other (then) Harapan allies.

Muda suffered from the same strengths and weaknesses of Harapan - limited Malay support, only a third of youth support, and uneven performance across seats.

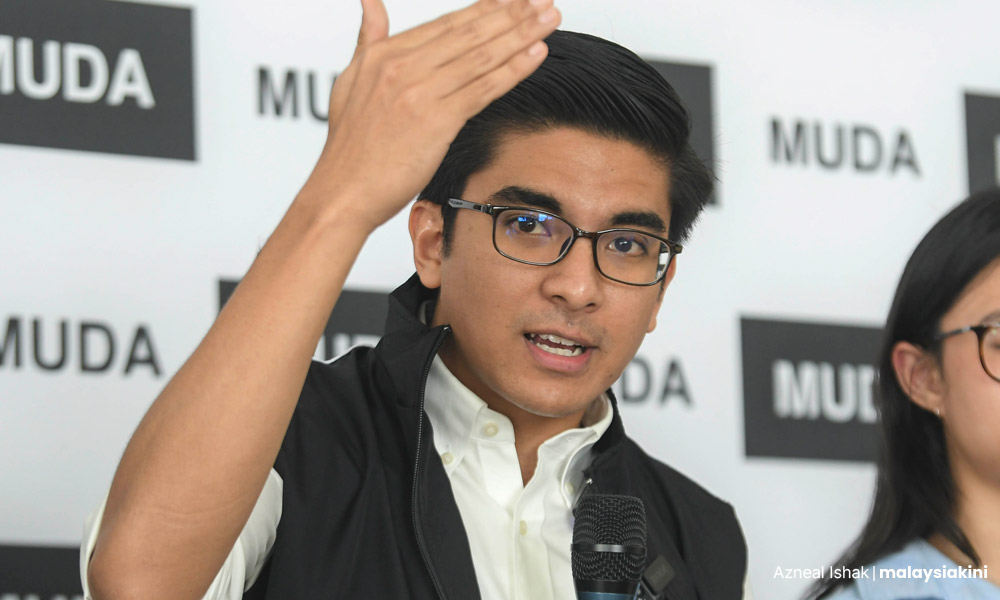

Muda’s strongest comparative advantage remained among 18-20-year-olds, who were brought into the electoral roll through reforms that the party’s lead leader, Syed Saddiq Syed Abdul Rahman, championed.

Like its Harapan allies, Muda performed well where it was an incumbent (and had time to campaign) - as was the case in Muar - where it held off the PN challenge despite the opposition coalition holding state seats in this constituency and the party’s disadvantage with resources.

There were considerable ironies in the short-lived Harapan-Muda alliance. Despite treating Muda as secondary, there were expectations that the party would bring greater youth support to Harapan.

Post-GE15, many in Harapan blamed the decline in support among youth for the coalition since 2018 on Muda rather than itself. There was also a view that Muda benefitted from Harapan support, supposedly “taking” what was already going to Harapan rather than on its own contributions.

Rarely was the reverse touted, that perhaps Muda’s presence offset an even lower level of youth support and that the party not only potentially strengthened Harapan electorally but also its alliance with the coalition undercut the potential support that Muda may have garnered.

Unfortunately, one cannot properly measure these alternatives. Few, however, even consider alternative views, as it would prove uncomfortable to self-reflect on potential shortcomings.

A generational divide

Muda became an easy target to blame for Harapan’s weaker-than-hoped GE15 performance. It is always important to remember that Anwar Ibrahim and Harapan were not elected to form a government on their own, and without others, they would not be in power.

The negative brand imposed on Muda has been reinforced since GE15. The view that Muda - made up of “only” young people - is a “small”, “minnow” one-seat party is deeply entrenched, especially among many Harapan leaders, as is the (unfortunate) parallel view that youth are secondary, marginal, and “minor”.

For some, the treatment of Muda has come to symbolise the secondary treatment of young people as a whole, the exclusion of members of a new generation of political voices. For others, Muda is seen as a young and overly ambitious upstart, impatient for change and inclusion.

There is a clear generational divide in outlook among some in the current government towards younger Malaysians. Youth are to be spoken at in town halls rather than with. They are to clean toilets to supposedly learn lessons, with little appreciation of the challenges today’s youth face, including catching up from missed lessons during Covid-19.

Through the old-fashioned lens, youth are seen to obey, to follow, to be denied decisions on their own health, and to be easily influenced - objects rather than agents of their own.

Worse yet, they are to be objectified, as inappropriately occurred in “ask for your number” remarks. The lesson on the value of apologising was missing.

Instead, there is an entrenched “elders know best” perspective, tapping into hierarchical (old-fashioned and undemocratic) views of young people. Ironically, these are the same entrenched views that Harapan has long challenged, many of whom were once impatient upstarts themselves.

Muda’s difficult political corner

Muda was placed in an untenable position, second (or last) class in an uncomfortable alliance and treated as its enemy on social media by its supposed allies; put (punished) in a far corner where it had only the option to leave. It has made its move to separate, one that arguably was made to be inevitable.

Most perspectives on the separation have highlighted the risks and challenges of going on their own. No question, without access to incumbency and resources, and facing persistent social media attacks, the party will be on an uphill electoral battle.

In a first-past-the-post system, winning the most votes is always difficult. It took PN three different elections to gain ground, and this came through building on PAS’s long-established political base and holding government.

The challenges Muda faces are also internal. The party has to come out of the shadow of being allied to Harapan and earlier to former prime minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad, who initially mentored Muda chief Syed Saddiq in politics (as the elder statesman did with many leaders including Anwar).

Since the Johor state polls, the party has showcased additional leaders beyond Syed Saddiq but in Malaysia’s highly personalised lens of understanding politics, he alone - his past compared to others who have even longer political tenures - continues to garner the most focus.

What Muda stands for needs to be better defined. The concept of #politicsbaru needs more clarity, as does Muda’s connection to youth and beyond youth.

Muda’s future will rest with reaching out beyond young people, while simultaneously strengthening its support among younger voters under 30, who now make up nearly 40 percent of the electorate (and increasing!).

New (more favourable) political conditions

The decision to go it alone is not an unusual one in Malaysian politics, perhaps most often practised by PAS historically. There are, however, particular features of current politics that make this decision more favourable than in the past.

First of all, voters have increasingly been looking to new options, to those that promise a different future. Party loyalty has declined, along with party membership. The space for new parties is arguably wider than before.

Weaker political parties (and patronage) have also moved mobilisation towards social media, where Muda has stated it will focus its mobilisation. It still, however, has a long way to go to challenge the well-funded PN’s social media dominance.

Second, despite the reality of a (large) younger electorate, most of the established political parties are not making way for younger leaders. They discuss the lack of young candidates, rather than acknowledging the holding on of older incumbents.

From Umno and PAS to Bersatu and PKR key parties are led by those in their 70s. In Harapan, it is only UPKO that has a leader close to Malaysia’s average age of its electorate, Ewon Benedick at (currently) 40.

At the same time, the mindsets (and battles) of national politics of key party leaders remain tied to the past, highly racialised, and personalised.

For too long, Malaysia has been held back by political squabbling. Muda will have to show it can be above the pettiness and vitriol that continues to plague national politics.

Third, the need for a viable, strong opposition is pressing. A vibrant democratic system has opposition parties from different perspectives.

Given the increased role of state governments, the place for constructive (not myopically focused on destabilising a government for personal power) opposition at the state levels is significant, especially oversight over the management of land, environment and state-owned companies.

That different parties are opting to contest state seats to speak about different issues and for different groups is a strength rather than a weakness of democracy.

Noteworthy, there is already a role for different parties in opposition at the state level. Not all the Anwar “unity” government parties are working together in states.

In Johor, Malacca, and Sabah, Harapan and BN parties, as well as Sabah regional parties/coalitions operate in different political configurations. Harapan is still the opposition in Johor as is Warisan in Sabah, for example.

Breaking from the past

A history of dominant centralised alliances did not create checks on power in the past. The implicit “we must get along” clamping down on different parties expressing different views on issues has not erased long-standing differences.

While the time to “agree to disagree and still work together for Malaysia” is gaining traction and Anwar’s government is focused on moving Malaysia forward, among parties there remains a focus on division and competition rather than on the shared interest of public service.

Yet, one should not underestimate the desire of the public (especially among voters under 30) for politicians to just get on with the job, address problems, make needed policy changes, and stop needless petty politicking - to move forward.

Importantly, Muda’s politics (so far) is comparatively less focused on divisive issues of race and religion and more centred on policies, service and deliverables.

With the hashtag #politicsbaru, Muda claims to let the present and future be the driver. In this regard, Muda is both the product of greater democratisation and its promoter, planning on offering more choices to voters.

No question, Muda will have to endure a long (and likely arduous) struggle. They will make mistakes. They are not alone in this experience in national politics. Malaysian politics is not an easy terrain.

Contemporary political history has shown that Malaysian politics is still deeply intertwined with her (more autocratic) past. Yet, the conversation about leaving her past behind is in itself a reflection of new, more democratic, realities. - Mkini

BRIDGET WELSH is an honorary research associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia’s Asia Research Institute (Unari). She is also a senior research associate at the Hu Fu Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies and a senior associate fellow of The Habibie Centre. Her writings can be found at bridgetwelsh.com.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.