Malaysia would be making history when the prime minister’s term is limited, as we would be the first standard parliamentary democracy to do so.

If it works out well, we may be emulated as presidential and semi-presidential democracies emulate the United States in presidential term limits, making it a norm.

So far, to our knowledge, South Africa is the only parliamentary democracy with a term limit for its head of state.

However, South Africa is a variant of parliamentarianism as its head of government, elected and sackable by Parliament, is called the president, who also assumes the head of state functions and has no monarch as a figurehead above him with some residual powers.

The rarity of term limits in parliamentary democracies must not lead us to think that term limits are exclusively suitable for a presidential system.

Term limits on the top job serve to ensure leadership renewal, avoid personal concentration of power to breed corruption, personality cult and political dynasty, and to avoid all-out power struggles induced by such unchecked power.

This is why even the one-party People’s Republic of China had a two-term limit for its presidency until Xi Jinping abolished it in 2018.

Neither should we think that we can simply replicate the presidential term-limit onto prime ministers without considering the inherent differences between parliamentary and presidential/semi-presidential systems.

Unaligned parliamentary and PM terms

One fundamental difference is the distinct or intertwined nature of legislative and executive terms.

In presidential or semi-presidential systems, the legislative and executive terms are fixed and distinct from each other.

Hence, former US president George Washington could set a precedent of self-imposed term limits by simply not seeking a third term.

In parliamentarianism, legislative and executive terms are intertwined and may vary in length for three reasons.

First, as the prime minister’s power derives from Parliament’s confidence, Parliament may remove a premier and get a new replacement, unless the ousted prime minister dissolves Parliament.

The case in point, Malaysia’s 14th Parliament, had three PMs: Dr Mahathir Mohamad, Muhyiddin Yassin, and Ismail Sabri Yaakob. Do you count each PM’s service period as a “term”?

Second, without a Fixed-Term Parliament Act (FTPA) in place, a premier may seek early dissolution without losing Parliament’s confidence. This shortens both the prime minister’s and Parliament’s terms.

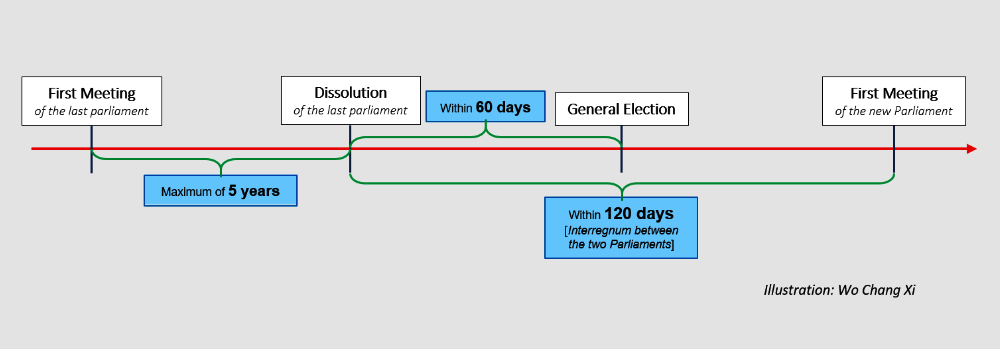

Third, with the known exception of Germany, there is an interregnum or gap between the last day of the last Parliament and the first day of the next Parliament, during which an election is held, and Parliament is formed before the new legislature convenes.

In Malaysia, this period is constitutionally allowed to reach 120 days. (See chart below) This interregnum would be shared between the outgoing prime minister in a caretaker role and the new premier.

The undesirable and desirable

Before going further on the scenarios where a term/tenure limit is applied, we must first identify the undesirable and the desirable from the standpoint of governance and political stability.

Clearly, we do not want either limitless rule or a frequent change of governments.

We want a capable leader to be able to pursue his/her policies in knowingly finite time. This makes self-initiated early dissolution without losing parliamentary support undesirable, which may be checked alternatively by an FTPA.

We, however, must not think that a mid-term change of prime minister is necessarily bad.

In the first place, one advantage of parliamentarianism over presidentialism is the flexibility to remove an unpopular government without an election. If a tenure limit results in a mid-term prime minister change, that should not be seen as a minus.

Scenarios with a term/tenure limit

This leaves us with four scenarios when a two-term limit (the first three scenarios) or a 10-year limit (the fourth scenario) is applied to the next prime minister.

The first scenario assumes that a prime minister would serve two full terms. This is a highly unrealistic assumption.

In Malaysia, only three out of 10 prime ministers (Mahathir counted twice) started with a full term. In the United Kingdom, only two out of seven prime ministers in the 21st century do so.

The second and third scenarios assume that a prime minister starts with a partial term left by an ousted, retired, or deceased predecessor.

If a partial term counts as a term, then a mid-term new prime minister is left with a full term at maximum (scenario 2). If a partial term does not count as a term, then the new prime minister can get two more full terms at maximum (scenario 3).

In the last scenario, a prime minister can accumulate 10 years across different terms. If he/she starts with a three-year partial term, then he or she can go on for a full term and a two-year partial term.

Unintended consequences to avoid

All these scenarios bring some unintended consequences that we must consider.

By counting a partial term as one term, scenario 2 brings three unintended consequences.

First, a prime minister who comes in mid-term would have a short period, which could be as short as six years, to serve, which is bad for policy continuity.

Second, for that reason, ambitious leaders may avoid stepping in mid-term, and such calculations may prevent the nation from getting the best candidate at the time of political crises.

Third, not far-fetched in a hung Parliament, to prevent a certain leader from going two full terms, his/her potential rivals may install him/her to be PM after an election, only to oust him/her afterwards and “exhaust” one term for him/her.

Scenario 3 brings a simple unintended consequence that stretches the limit to nearly three terms.

A seat warmer may be installed as prime minister but quickly removed (if he/she does not voluntarily resign) to make way for the next prime minister to go for nearly 15 years.

With a 10-year limit, Lee Hwok Aun of Iseas-Yusof Institute lists three unintended consequences of scenario 4.

First, a prime minister might have to resign in the middle of his/her third term.

Second, a prime minister helming a coalition at the end of his/her 10-year limit may become a lame duck and even face a government collapse due to coalition partners’ defection, and even a snap election may be triggered.

Third, a second-term prime minister may be tempted to call an early election so that he/she may appeal for a five-year mandate.

Lee calls for an FTPA in a package with a two-term limit. An FTPA would certainly help deter self-initiated early dissolution, but it cannot ensure a single government throughout a parliamentary term.

(In Malaysia’s context, FTPA can codify the loss of confidence and confine it to confidence and supply votes, ruling out the statutory declaration shopping game and hence enhancing political stability.)

A mid-term change of the prime minister need not be feared, as it is more normal than we may realise, as shown in the Malaysian and UK examples above.

If a coalition government collapses because the new leader cannot command the support of all components, it may lead to either an early election or a reconfiguration of the coalition government for the remaining term.

Both are within the rules of the game for hung Parliaments.

Proposal: 10 years with a six-month buffer

Comparing the unintended consequences of the three realistic scenarios (2, 3, 4), the verdict appears clear to us: 10 years, not two terms.

However, there is a catch: 10 years may not be able to cover two full parliamentary terms because of the interregnum that can stretch to 120 days, the extra weeks that a prime minister presides before the new Parliament sits and as the caretaker premier after dissolution.

Fortunately, there is a simple solution: just add a six-month buffer to cover the interregnum. This would incentivise a prime minister aiming for two full terms to have the new Parliament sit early.

It would be great to have an FTPA in a package, but one bird in hand is better than two birds in the bush. - Mkini

WONG CHIN HUAT is a political scientist at Sunway University and a member of Project Stability and Accountability for Malaysia (Projek Sama).

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.