“During the school holidays ‘Ryan’ worked every day except Sunday. Last week he worked about twelve hours and came home tired. We were not home … dinner had been left on the table but he didn’t eat it.

“Ryan went out late at night with a close friend to the nearby lookout, his usual retreat. It was cold and bleak. He was weary, profoundly sad. Life seemed unpredictable. And, he had no particular plans after his HSC.

“Ryan was overwhelmed with despair. For a moment he was blinded from reason. It only took a moment to climb that low rail and leap. Within seconds he was taken from us.”

A grieving mother circulated this (edited) note at Ryan’s memorial service years ago, as if seeking answers to why her 17-year-old son did what he did, and if the family could have seen the warning signs.

The triggers of suicide are hard to pin down. A few of my students had committed suicide during my teaching years. With limited experience in supervising graduate students gripped by persistent crises, where hopelessness and helplessness had collapsed into dark despair, could I have done more besides referring them to the university counsellor?

These thoughts recur each time I read of youth suicides, increasingly among vulnerable international students who went through episodes of grappling with new learning environments, socioeconomic and psycho-cultural distress. Having studied in foreign environments, I can empathise with that.

We know from ongoing research a great deal more about the probable causes of suicides that have torn apart families, weighed down by lingering ‘what-if’ they had seen the warning signs. But could they have? Could we?

In a perfect world, one could ‘predict’ and 'prevent' suicides. The reality is much more complicated. This testimony from a suicide survivor explains why. Behind the smiling façade, sometimes, lies a crushing pain. When the unbearable pain exceeds the coping resources, suicide happens.

I had spoken with a suicidal lady who related how her pet dog helped snap her out of overdosing. Today she is today managing her bipolar disorder with medications.

I know of two other church-going members, outwardly ‘normal’ with ‘normal’ down days, as many of us go through sometimes, who committed suicide at home. Could friends have seen the warning signs and ‘did something’ to intervene?

The US-based RAND Corporation notes in a study that “warning signs were a daily fact of life, not a red flag … and it would have been hard to see them for what they were against a backdrop of distress or depression”.

In our Malaysian family experience, depression (lingering sadness?) is often unrecognised. If it is, it may be cast as the millennial’s lack of mental resilience. At worst, family members may deny depression as real, even as a Health Ministry survey in 2017 notes that the 13-17-year-olds are most at risk.

Add social media trolling to the equation and the risk of adolescent suicidal ideation, the precursor to completed suicide, jumps a notch.

An earlier study in 2014 notes that suicidal ideation prevails among “females of Chinese and Indian ethnicity, and from broken families”. Perhaps socioeconomic location, spiritual well-being and family support are reliable ‘preventers’ of suicidal intent?

How preventable is suicide when it is still whispered about and considered a criminal offence, despite persistent calls for its decriminalisation?

There is scant empirical evidence that criminalising suicides has significantly deterred despondent adolescents from taking their own lives. While decriminalising suicide de-stigmatises the act, arguments for repealing Section 309 of the Penal Code in India, Singapore and Malaysia are as many as the against.

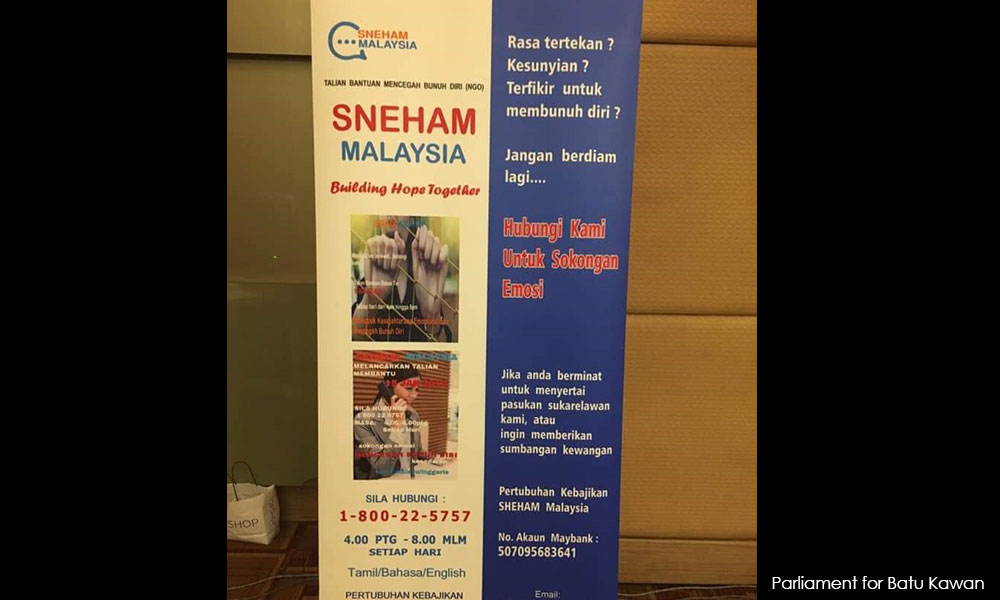

That having said, the core to ‘preventing’ suicides is to mandate that the mentally ill and suicide-prone get all the help and critical follow-up they need. But where will they find this help? Who can notice their cries for help when suicide remains a taboo?

Befrienders note that “for many people who feel suicidal, there seems to be no other way out. Death describes their world at that moment and the strength of their suicidal feelings should not be under-estimated - they are real and powerful and immediate. There are no magic cures.”

Notwithstanding the Mental Health Regulations 2010, which provide for the delivery of community mental health care centres, it comes down to how we perceive, respond to and care for the mentally ill, and not as stereotyped suitors for Tanjung Rambutan. It comes down to family and friends connecting with and helping suicidal adolescents find some hope and purpose in continuing to live - for themselves and their loved ones.

The media in this instance plays a critical function in changing mindsets about mental illness and minimising harm in its reporting of suicides, as recommended by the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, and US-based reportingonsuicides.org

There are many resources available now on how to prevent suicides or help families navigate through their grieving over the loss of a loved one through suicide.

This silent illness will not be completely preventable, but it is far from being inevitable, which, unfortunately to family and friends of Ryan, is small consolation.

ERIC LOO is a Senior Fellow (Journalism) at the School of the Arts, English & Media, Faculty of Law, Humanities & Arts, University of Wollongong. He is also the founding editor of Asia Pacific Media Educator. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.