With great fanfare, the Islamist party PAS and Malay-nationalist party Umno joined forces officially this month to become a broader opposition force. Touting itself as a political alliance for ‘Malay unity’ to ‘protect Islam,’ long standing enemies became brothers to fight against the governing Pakatan Harapan.

On the surface, this move may appear to be a strategic one, in which the combination of the bases of support of both parties will put it in a potential position to win national power. A closer look suggests that the alliance faces more obstacles than has been publicly acknowledged.

Despite these hurdles, however, and looking at different electoral scenarios, the alliance poses a real threat to Harapan.

Troubled national leadership

The first major obstacle facing the opposition alliance is a lack of viable leadership. Neither party president - PAS leader Abdul Hadi Awang or Umno’s Ahmad Zahid Hamidi – have the national credentials to lead the country as prime minister.

Hadi’s racialised discourse makes him one of the most polarising leaders in the country across ethnic communities. His five-year rudderless and exclusionary leadership of Terengganu from 1999 led to the loss of the decisive state in the 2004 general elections.

Zahid on his part has the disgrace of being the party president facing the most criminal charges, currently at 45, and will be joining his predecessor in regular visits to the courtroom. Zahid’s close alliance with former party leader Najib Abdul Razak further undercuts his standing, as Najib continues to overshadow Zahid.

None of these leaders has the legitimacy to get elected, least of all move the country forward.

A parallel question is who will lead – PAS or Umno? Traditionally, Umno has been seen as the stronger party. This is no longer the case. Of the two parties, PAS is stronger institutionally and financially. Importantly, it is controlling the narrative.

PAS has shown in recent years that it is unwilling to accommodate alternative leadership. One of the factors that led to the breakup of Pakatan Rakyat was its unwillingness to accept Anwar Ibrahim’s leadership.

Umno has also not played the second fiddle role. Its resistance to accommodation contributed to the demise of Barisan Nasional. Inevitably, the partnership of convenience will face the challenge of cooperation. It is important to appreciate that previous Umno-PAS/Umno-Semangat 46 alliances were undermined by personality differences and power struggles.

PAS, in particular, does not have a record of long partnerships. The new opposition alliance will face similar challenges in cooperation – in which views of the past will colour perceptions and trust.

Internal divisions

One of the flawed assumptions made about this alliance is that there is broad agreement on the alliance itself within the parties concerned. At the grassroots level, helped by a media that has worked to demonise Harapan (especially DAP), there is support for the initiative, with greater reluctance in traditional states of enmity such as Kelantan and Terengganu as compared to Selangor. The main obstacle is within the leadership of the opposition parties, notably Umno.

Umno is divided over whether to support the alliance, as the decision to form the alliance corresponds to sharp differences within the party about the future of the party itself. The most divisive issue involves party leadership.

Najib’s decision to return to the party as ‘advisor’ has caused deep resentments as it signifies to many that he (and his allies) are putting personal interests over that of the party. There is a perception that he is pouring money to pay for trials and personal reputation building rather than rebuilding the party. This comes on top of his proxy’s (Zahid) return as president, which displaced the leadership of Mohamad (Mat) Hasan that was responsible for rebuilding the party’s reputation and securing a series of by-election victories.

Behind the question of leadership involves not only the relationship with PAS but the leaning of the party toward Prime Miniser Dr Mahathir Mohamad or Anwar, with the different camps favouring different leaders. Who the party is allied with is contested, as there are different perceptions on how the party can return to power.

Finally, the party is split generationally, with those wanting to return to the past and those recognising the need for reform. Those favouring the PAS alliance are the most resistant to reform. Over the last six months – despite the well-funded social media presence of Najib – his camp has lost ground within the party. It was striking to see who was not prominent at the PAS-Umno event, rather than the spectacle of the event itself.

PAS similarly faces divisions over the Umno marriage of political convenience. While the internal splits are less severe, as the party experienced its most recent divisive break when Amanah was formed after the 2015 muktamar and those around Hadi consolidated power, there is more quiet resistance to working with its old foe.

Many in PAS recognise they won the state governments of Kelantan and Terengganu by defeating Umno, by being the non-Umno. Some believe that openness to Umno will strengthen the party’s base. Others believe this might undermine the party as there are concerns that the intrusion of Umno money politics culture is corroding PAS.

Persistent corruption allegations continue to smart for PAS, and a stronger alliance with a deeply corruption tainted Umno will only strengthen perceptions of accommodating leaders who many believe used power for personal ends. PAS’ standing and identity are changing, and despite being the dominant partner, it has been shaped by Umno and vice versa.

Polarising campaign

Another important obstacle involves the role race and religion play in party identity and positioning.

Both Umno and PAS have long moved historically along a continuum tied to more inclusive nationalism to exclusive ethnic posturing. The current opposition alliance’s positioning is among the most exclusionary yet for both parties – combining the Malay supremacy nationalism of Umno with a defensive narrow, conservative and exclusionary view of ‘protecting Islam’. It rests on the idea of internal and external enemies, feeds on anger and aims to capitalise on displacement and disgruntlement.

Increasingly much of the positioning is tied to sensational (and sometimes fake) news that divides Malaysians from one another. The level of demonisation of fellow Malaysians that has begun, even before an election, is deeply worrying. There are parallel reactions by others on the political divide that are equally strong and hurtful. This dynamic is dividing Malaysia, contributing to the worsening of ethnic relations, intolerance and increased hate speech.

From those involved, this reflects a world view and strategic targeting to win power, but there is little appreciation of how this will be perceived outside – a polarising racialised approach will not bring in foreign investments, it will not showcase Malaysia’s strengths. Across the world as the middle ground and the centre have contracted, the negative costs to national fabrics are clear. It will be very difficult to repair the damage and ameliorate the risks this type of divisive politics can bring.

By making other Malaysians the enemy, the challenges to moving toward national integration will deepen. As the old adage states, be careful what you wish for – polarisation will make Malaysia more difficult to govern.

Support levels and gaps

When you run numbers by ethnic voting and different voter turnout levels, the PAS-Umno alliance has strengthened its electoral position. To date, Harapan’s erosion of political support and buy-in to race-based politics (in which it is inherently the loser) has furthered the chances of this alternative. There is a real chance of lower support and turnout for Harapan, as evident in most of the recent by-elections. Numerically, it would seem that PAS and Umno joining forces have increased their chances of winning national power. And they can win power.

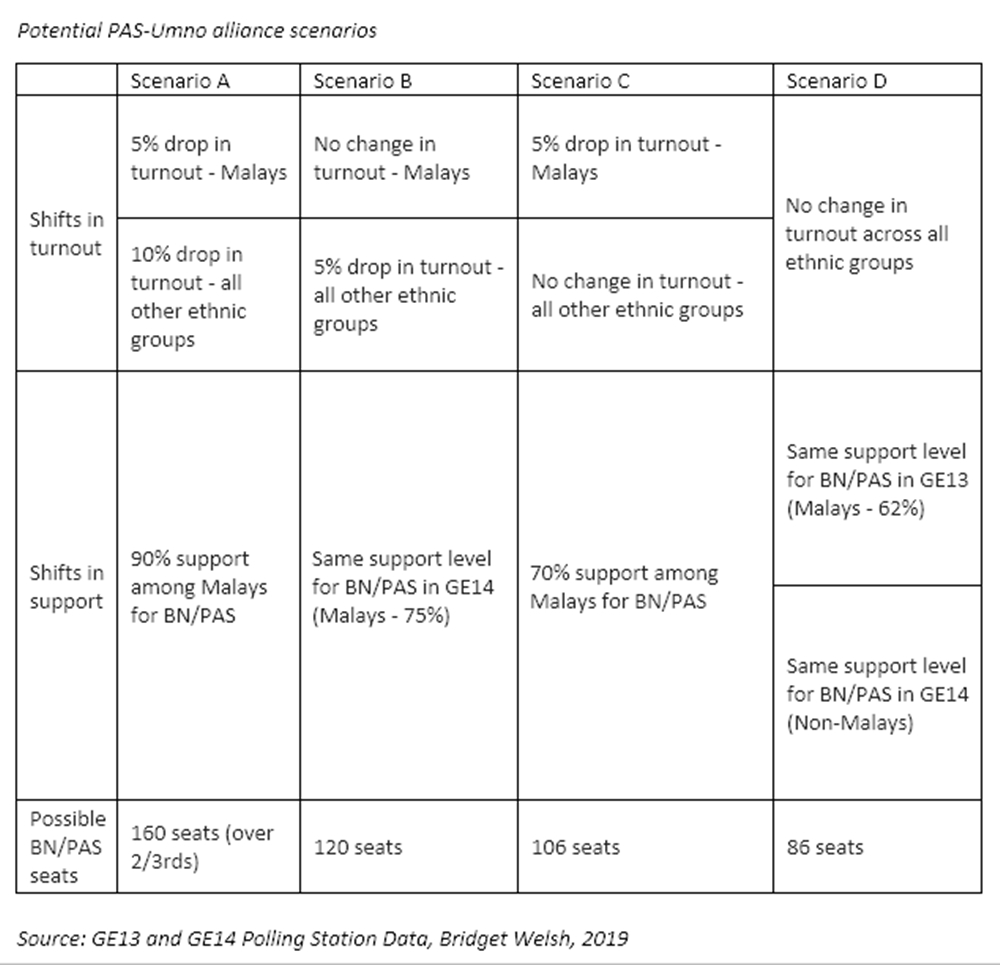

Drawing from the polling station results, I have prepared four scenarios, from A to D. In Scenario A, PAS and Umno capture the overwhelming majority of voting Malays (90%) and disgruntled Malays who voted for Harapan, and non-Malays do not turn out to vote for Harapan in the same numbers. In this scenario, the PAS-Umno alliance wins emphatically.

Scenario B involves lower support levels among voting Malays (75%) and less changes in national turnout but shows that a drop in turnout would make Harapan vulnerable. Even a small drop in turnout among non-Malays and same GE14 level of support for PAS and Umno can lead to a Harapan loss.

In Scenario C, PAS and Umno win the lion share of Malay vote (70%), but turnout levels among non-Malays remain consistent. Harapan would stay in power. In the final Scenario D, the support among Malays for Harapan increases to GE13 levels and non-Malay support remains the same, leading to a larger victory and loss for PAS and Umno.

The scenarios show that there are a range of outcomes, but that Harapan is vulnerable. The PAS-Umno alliance has put the opposition back in the political game, while the governing coalition has lost ground. While the PAS-Umno alliance is more a reflection of individual party weakness rather than strength – it is now a national contender.

This said, these scenarios however should be treated with caution. They are markers of possible outcomes in a more uncertain political environment. Importantly, the scenarios are premised on previous voting patterns and are minimalist in their assumptions. The opposition is weaker than it was in GE14 and the alliance itself is a different political entity. Umno no longer has the resources to run the same type of campaign and nationally PAS has weaknesses in its machinery.

The alliance is also an electoral liability in some states, for example, Sabah (where Umno may become ‘autonomous’) and Sarawak (where PAS has gained ground but is still weak). Key support groups of the opposition parties may react differently to the alliance as well, notably women who have long disproportionately voted for Umno and rejected PAS.

It is important to understand that voting is not just along ethnic lines. The next election will have a different, younger electorate. As the terrain changes, it is important to bring in and assess these changes and look at the electorate more multi-dimensionally.

Harapan will also be different. It may not be the same coalition and it will most likely not have the same leadership going into the next election. The opposition alliance will face a new opponent, one that despite Harapan’s vulnerability will have at its disposal greater resources and the power of incumbency. The question is whether Harapan will be able to reverse its recent erosion of support and respond effectively to the changed political terrain. The same issues – leadership, divisions and campaign narrative – are relevant for Harapan as well.

In short, the PAS-Umno alliance may appear to have a stronger electoral position. They have greater chances of winning, but they have real obstacles of leadership, division and polarisation ahead that will impede their chances. Harapan however should not dismiss the reconfigured opposition. One of the important lessons of GE14 in which the then opposition won power, is not to rule out reconfigured opposition alliances.

BRIDGET WELSH is a Senior Research Associate at the Hu Feng Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies, a Senior Associate Fellow of The Habibie Centre, and a University Fellow of Charles Darwin University. She recently became an Honorary Research Associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia's Asia Research Institute (UNARI) based in Kuala Lumpur. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.