Even as we grapple with Covid-19, let's keep our eye on what our politicians are up to.

Just as vigilance is needed for our public health during a pandemic, eternal vigilance is what is needed for our political health, following a power grab.

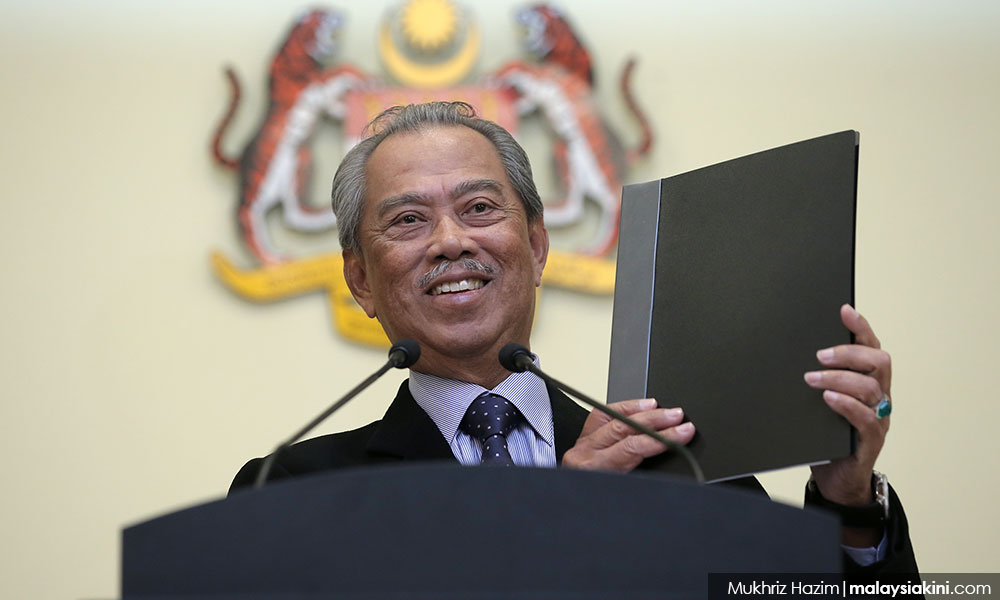

In my column this week, I confront the questions surrounding Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin’s backdoor government. Is his government legal and constitutional? Is it legitimate?

To help me clarify these questions for Malaysians, I speak with Dr Wong Chin Huat, who is a political scientist at the Jeffrey Sachs Centre on Sustainable Development at Sunway University.

Q: Some say Muhyiddin’s government is legal and constitutional, but illegitimate. How do we distinguish between legality/constitutionality and legitimacy?

Legality/constitutionality is about procedural compliance. Legitimacy is a higher standard. It is about what is right ethically and as a norm for correct or right behaviour. In other words, what is legal and constitutional may not be legitimate.

In Malaysia, we practise the parliamentary system. This is a system where people only elect the members of Parliament, who then elect the government. Parliamentarianism varies in different countries. And the rules in each system determine what makes something legal/constitutional.

For example, there are differences between Germany and the UK. In the UK, the Queen is a figurehead who stays above partisan politics. She appoints as prime minister whoever leads the majority party. In the case of a hung Parliament in the UK, the ruler appoints as PM whichever party leader can command the confidence of Parliament.

In Malaysia, the Yang di-Pertuan Agong is bound by Article 43(1) of the Federal Constitution. This states that the ruler has the discretion to appoint as prime minister “a member of the House of Representatives who in his judgment is likely to command the confidence of the majority of the members of the House”. The clause makes no mention of political parties. Conventionally, this omission was never a question because a formal coalition, Barisan Nasional (BN), always won the parliamentary majority. That was, until the last elections in 2018.

Q: So, is Muhyiddin’s government legal and constitutional? Is it legitimate?

When both Muhyiddin’s and former PKR deputy president Azmin Ali’s blocs withdrew from Pakatan Harapan and Dr Mahathir Mohamad resigned on behalf of the Harapan government – instead of just himself so that Harapan would be a minority incumbent – we had a hung Parliament. Unlike in Germany or the UK, we have no guideline other than Article 43(1) to ascertain which MP has the majority.

This gave room for MPs to go back and forth on who they actually supported, some more than once. For example, former minister Maszlee Malik reversed his position a few times in one day.

In the technical sense of Article 43(1), Muhyiddin’s government is hence constitutional. His government’s constitutionality will continue until he loses a vote of confidence, or its supply bill (ie the budget) is rejected. Should that happen, he must resign or seek royal consent to dissolve Parliament.

Legitimacy is another question altogether. Legitimacy would depend on whether Muhyiddin complied with democratic norms when forming his government. Legitimacy does not change with him either surviving or avoiding a vote of no confidence. It’s like having respect. A court may find you innocent but that doesn’t mean you’ll have the public’s respect.

Q: Does the accusation of a non-elected government make Muhyiddin’s government illegitimate? Does that hold water when his main partners – BN and PAS – actually won 51 percent of popular votes, more than Harapan's 48 percent, in the last elections? Is his government illegitimate because it includes the corruption-tainted Umno? Or because it is not multi-ethnic?

As stated earlier, constitutionality rests on the Constitution. The question of legitimacy rests on norms or values. There are at least four values that give us grounds to call Muhyiddin’s government illegitimate.

The first is integrity. This is not the only ground, however. If this were the only ground, then the simple solution would be to exclude from the government the six Umno MPs who are facing corruption charges.

This is Mahathir’s main demand, which Muhyiddin has technically met. Additionally, Umno has declared it is no longer part of the Perikatan Nasional (PN) government because it feels sidelined in Muhyiddin’s cabinet. With Umno ministers and deputy ministers in government only in their individual capacity, Mahathir’s demand is again met.

The second ground is inclusion. A predominantly Malay government poorly represents Malaysia’s plural society and is likely to affect its performance, too. However, there is a danger in over-emphasising multi-ethnicity. We may end up demanding a grand coalition government with no opposition, much like what our second prime minister Abdul Razak Hussein tried to achieve after 1969.

The third is manifesto as embodied in Buku Harapan’s reform agenda, and the fourth is mandate. Manifesto and mandate are intertwined but should really be separate in our analysis.

It’s like this: people voted in a Harapan government based on the Buku Harapan manifesto. A mid-term change of government makes voting meaningless and a betrayal because of a default in contract.

Based on election promise alone, a Mahathir-centric party-less government unconstrained by Buku Harapan would not have been much better than Muhyiddin’s. The only difference would have been in personal branding.

Q: But why must the nation’s future be decided by the 48 percent of voters who voted for the Buku Harapan manifesto, if the 34 percent of BN voters and 17 percent of PAS voters can compromise? And aren’t post-election coalitions common in parliamentary democracies?

The short answer is the last election was fought on the first-past-the-post (FPTP) system with Harapan and BN in a clear two-bloc competition. Under the FPTP system, a coalition only needs to win the majority of seats in Parliament to form a government, even if it doesn’t win the majority of the popular vote.

That is the rule of the game under the FPTP system. You can’t change the rule midway after playing the game so that you benefit from that rule change.

The longer answer is PN is not a normal post-election coalition. Post-election coalitions, even minority governments, can work well. But that requires serious inter-party negotiation on policy differences, not a fishing competition for frogs using ministerial positions as bait. This makes both the PN government and Mahathir’s proposed presidential government equally illegitimate.

Q: The Sultan of Selangor has declared it is inaccurate to describe the PN government as a “backdoor” government as the Yang di-Pertuan Agong has discretionary powers to appoint the prime minister. What do you think?

A constitutional monarchy is premised on a non-partisan head of state. Both sides of the political divide are each His Majesty’s government and His Majesty’s loyal opposition.

While the monarch in Malaysia has the discretionary power under Article 43(1), citizens have every right not to have confidence in the prime minister. Equally, the Opposition has every right to move a vote of no-confidence.

Doing so does not disrespect the Agong. Rather, this strengthens a constitutional monarchy by ensuring popular sovereignty. Any constitutional monarchy would be in danger if monarchs and citizens cannot see its compatibility with free speech and informed choices.

Q: What do you think is the most accurate way to describe the new prime minister and his government?

What we have seen so far in Muhyiddin’s government is not just Malaysia’s second-largest administration, smaller only than Abdullah Badawi’s 2004 cabinet, to buy off parliamentarians. His government has also resulted in an immediate fight over ministerial positions, resulting in one less deputy minister and Umno’s self-exclusion.

More accurate than calling it a “backdoor” government would be to call it an “alliance over spoils”. Muhyiddin’s government is united by the pursuit of spoils and is now split over its division.

Q: Right after Muhyiddin’s appointment, many media outlets treated the appointment and the new government without any hint that there was a contest over its legitimacy.

What role do you think the media needs to play to be more critical about the power grab in Malaysia?

Regardless of which party or coalition is in power, the media should always strive to be the fiercest watchdog of the government, and never its tail-wagging lapdog.

Q: If Muhyiddin’s government is illegitimate, what kind of relationship can civil society organisations, and citizens in general, have with this government?

Illegitimate as it may be, Muhyiddin’s government is constitutional. Out of respect for the office, civil society organisations and citizens should still engage and cooperate with the government on policy and other matters, such as the movement control order.

We must recognise that the system needs a proper overhaul. Post-coalition governments may be necessary but it cannot be done through seat-buying. Amphibian politicians should respect our mandate and not sell it to the highest bidder. Even if Muhyiddin’s rojak government performs well, we should qualify its performance on its legitimacy. We should not overlook illegitimacy for performance.

Q: Short of mass rallies to protest what has happened, which would not be possible anyway because of Covid-19, what else can citizens do to protest a government they did not elect?

Because of how multiparty democracy has been turned into the bogey, it would be hard to organise a multi-ethnic mass rally like Bersih 5. More frustratingly, even a successful mobilisation may offer only two unappealing prospects: a new government replacing PN propped up by some frogs, or a fresh election without deeper reforms, which would result in a similar dead-end or greater instability.

However, there are two ways to strike back at the coup. One, close the ethnoreligious divide to make multiparty democracy resilient. And two, push for deeper institutional reforms, such as having recall elections, where voters can fire politicians, and an electoral system change.

JACQUELINE ANN SURIN is a Drama@Work consultant, a specialist meeting facilitator and a leadership coach. She was an award-winning columnist, a journalist for 20 years, and the co-founder of The Nut Graph before switching careers. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.