Doing business in Malaysia has its own set of peculiarities, sensitivities, creativity and the occasional idiosyncrasies.

Ever since the "Ali Baba" system started with the introduction of the affirmative policies in 1972, this has been modified, revised, amended and adapted to accommodate the needs of the situation and its surroundings.

Depending on the quantum and portability, the system is worked on by insiders or personalities at almost all levels of government – from the office boy in the hawker management office to the highest echelons of government.

You don’t have to look far. The evidence adduced in ongoing court cases speaks for themselves. Businessmen are will to part with millions of ringgit to people at the highest level without batting an eye – the higher the level, the better the chances of landing the job.

At the highest level, one businessman allegedly tackled the wife of the former numero uno in an attempt to get the contract. For him expanding or “investing” (as some see it) large sums of money on individuals who wield power through their office, or via pillow talk, provides a return on his investments.

Who would have thought of this philosophy - to get close to the minister, you must first get close to those who are close to this person. Investigating a corruption case about 10 years ago, the businessman who was soliciting for a massive contract explained (with a straight face) why he paid for the business class return airfare to Hawaii for the minister’s personal fitness trainer.

Elsewhere, a state executive councillor animatedly elucidated why he had set up an ad-hoc committee comprising his cronies to handle the allocations of Chinese New Year stalls. When it was left to the council, he reasoned, it would be a difficult process. So, the committee would collect a processing fee after which everything would be arranged.

Then there’s a thing called "persatuan" (association) which collects fixed fees from traders as "yuran pengurusan" (management fee). There’s no proper governance – no proper account keeping except that on the trading day, one or two will be walking around with receipt books. Nobody knows where the money goes and how it is spent. And no one has a clue to the persatuan, its membership or officials.

Against this backdrop, large sums of money have been collected over the past months by organisers for stalls during the Ramadan bazaar in Kuala Lumpur. The bazaars have been cancelled because of the coronavirus outbreak and the movement control order.

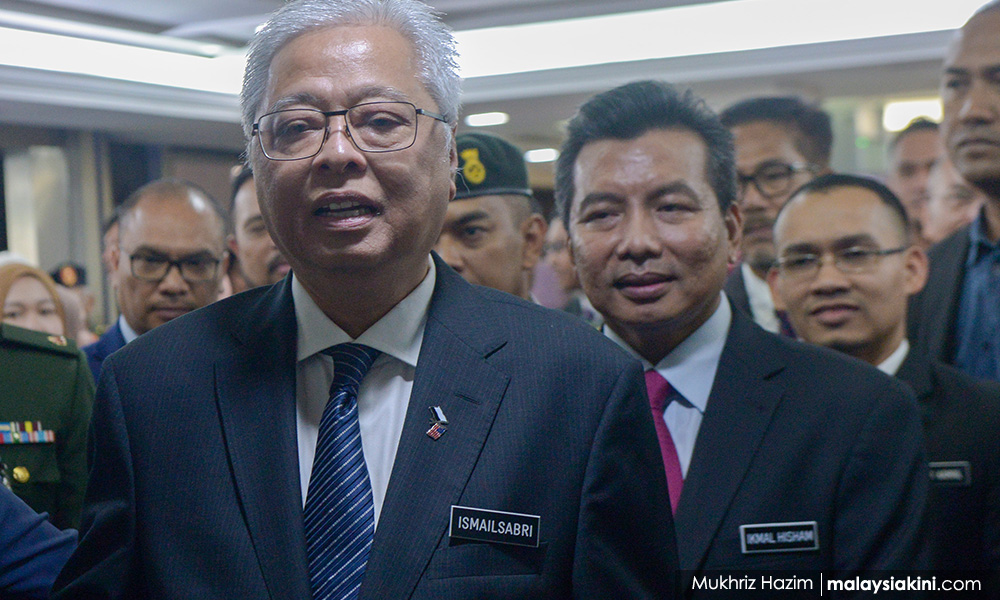

Defence Minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob is now asking for the monies collected by “Ramadan bazaar organisers” to be returned to the hawkers.

He is pleading, hopeful that some sense will get into the heads of these organisers – but will it? Who knows where the money is and if it has filtered to the pockets of those within?

“No one should take advantage of someone else’s troubles. They paid their deposits in the hope that they can set up a stall, but the government has decided to ban Ramadan bazaars. Please return the entire deposit or payments they’ve made,” Ismail pleaded at a press conference in Putrajaya yesterday.

The least of the problems is for the Kuala Lumpur City Hall (DBKL) to refund the RM120 each it collected as licence fee. The process is already in motion. But what about the monies which are in the hands of the organisers?

To answer that question, few more have to be addressed, namely:

- Who are these organisers?

- Are they collectively or singularly or legally set-up?

- What assets do they own?

- Who allowed or sanctioned them to operate as organisers?

- Did DBKL authorise the collection?

- If it did not, why didn’t it stop the practice, knowing that it is in existence?

- Did DBKL or any local council authorise and recognise their existence?

- If they did, which provisions of what law provided for it?

- Why did DBKL choose to have dealings with a non-registered entity?

And more importantly, does DBKL know the people involved or have efforts been made to untangle the web of cross-holdings and bank accounts?

In Kuala Lumpur, traders are said to have paid bazaar organisers between RM250 and RM800, including RM120 in licensing fees. So the organiser is making a small packet.

But the figures are being underquoted. According to former Federal Territories minister, Khalid Samad, who tried to break the stranglehold of the bazaar organisers, it could be as much as RM30,000 per stall depending on the location.

Even if that is considered to be on the high side, a conservative calculation of organisers collecting an average of RM2,000 each for the 5,000 lots located in 65 locations in the federal capital amounts to RM10 million. That’s a lot of money.

So, how are the hawkers going to get back their money? City Hall will rightly wash its hands as it did not collect anything more than the prescribed fee of RM120. The rest is pure profit for a few.

Can they be brought to book? Yes, but it would be time-consuming and an uphill task. The organisers most probably would melt into the crowd and mere first names would be thrown about during preliminary inquiries without proper identification. At the end of it all, yet another file would be gathering dust in the steel cabinets with the letters NFA (no further action) emblazoned on it.

However, City Hall cannot run away from its moral and ethical responsibilities because it allowed such a system to operate and acknowledged the existence of bazaar organisers and the systems they operated.

However, the biggest blame of all must fall on the politicians – who created, cultivated, nurtured and built this system to an art – a source of funds to feed the frenzy of their cronies who, too, wanted their fair share of the spoils.

By the way, there are more techniques for doing business the Malaysian way. It is only that they have not been made public or are yet to be utilised.

R NADESWARAN does not understand the need for crony systems to thrive, especially in urban Kuala Lumpur. Comments: citizen.nades22@gmail.com. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.