One afternoon, when I was about 13, my family was startled by the shouts of an angry man and a woman’s terrified screams outside our house. We rushed out as did all our neighbours.

The enraged man was yelling at the woman while repeatedly smashing her with his helmet. She had fallen on the road and was crying and screaming for him to stop as he towered above her. He continued bashing her even as she cowered and tried bravely to protect herself with her arms.

In the midst of the commotion, somebody recognised the pair as the married couple who lived in the kampung house at the end of our row. Everyone was stunned even as motorists began to slow down to watch the spectacle.

Trembling with horror, I rushed back into the house and dialled 999. A woman was being beaten up with a crash helmet. I was scared she was going to be terribly hurt or that she would die right in front of us.

When my call was answered, I gave my name and address and described the situation. To this day, I will never forget what was said to me: “If this is a domestic matter between a husband and wife, it’s not a police case.”

I’m not sure where I found the resolve to retort: “Okay, and if you don’t send the police, and if she dies, that’s on you.” There was a pause on the line, and then I was told a police squad would be dispatched.

By the time I went back outside, the abusive man had paused hitting his wife. I don’t know what made him pause – maybe it was the crowd witnessing his crime or the neighbours imploring him to stop. I can’t remember if the men physically tried to restrain him. But I do remember that he paused so he could drag his wife back by her hair to the privacy of their house.

There was a brief lull. At some point, the police arrived and were directed to their house. They went in. Then they left without any other action.

Over the next few years that we all lived on that street, we would frequently hear the yelling and screaming from that kampung house. There was not very much any of us could do. Those were the days before the Domestic Violence Act. And there was scant awareness that domestic violence was a crime and not just a private matter between a husband and wife.

Eventually, the couple moved away. I don’t know if she ever survived that brutal and abusive relationship. But I do know that she never left it while she lived on that street with him.

I share this story because it left an indelible print on me about the nature of domestic violence. It taught me a lot about the dynamics of power and abuse in our most intimate relationships. And it made me hyper-aware of the unique threats to safety and life that women and children endure when there’s violence at home.

I so wish our Deputy Women, Family and Community Development Minister Siti Zailah Mohd Yusoff (above) had been exposed in the same way.

Last week, Siti Zailah, who is also the PAS Wanita chief, posted a five-minute video to offer tips on how to manage domestic violence during the extended movement control order (MCO).

After watching it, I really wanted to ask the deputy minister: “What planet are you from?”

Siti Zailah provided three tips – physical, mental and spiritual – for managing domestic violence. To the perpetrator, she says, if you’re feeling angry, sit down, or lie down, or take ablution, or just keep calm and quiet until your anger subsides.

To the potential victim, she says, always think of the 1,000 other things you appreciate about your husband. Use the “magic words” of “thank you” and “I’m sorry”. And if you’re Muslim, lift up a special prayer for a happy family.

What’s most apparent about the video is how clueless the deputy minister is about the nature of domestic violence.

In the interest of ensuring taxpayers money is used to protect women and children, here are some tips for you, Siti Zailah:

Domestic violence is violence. Let me spell it out for you - violence means somebody actively hurting you physically or psychologically, or both. It is nowhere the same as the regular squabbles couples have because of annoying behaviours or a difference in opinions or attitudes.

As a way to understand how vacuous your advice is, imagine telling a potential victim of violence the following: “If you know the person you live with is going to slap you, or smash your head in, or break your limb, or rape you, or murder you, remember the magic words of ‘thank you’ and ‘I’m sorry’ to keep relations harmonious.”

Domestic violence is a crime. That means it is so severe that under Malaysian law, a convicted perpetrator can be imprisoned and fined.

Run-of-the-mill spousal grievances like a nagging or angry partner are not crimes. They may be annoying and frustrating but they do not cause harm in the way that violence does. That’s why nagging or being angry aren’t crimes in Malaysia or other parts of the world. So please, don’t advise women about how to manage nagging, or how to control anger, or how to be thankful as a means to address domestic violence. Unless, of course, you want to come across as being delusional.

If you had only done just a bit of research on domestic violence, you could have avoided looking like an unfit deputy minister. For example, the Missouri Coalition Against Domestic and Sexual Violence describes the nature of domestic violence as “neither random nor haphazard”.

Unlike the description in your video, domestic violence is not caused by the rising irritation and anger one feels towards one’s spouse. Domestic violence “is a complex pattern of increasingly frequent and harmful physical, sexual, psychological and other abusive behaviours used to control the victim. The abuser’s tactics are devised and carried out precisely to control her.”

To suggest using anger management tactics to stop domestic violence is like suggesting to a calculative and deranged criminal: “Just take deep breaths while counting to 10, and you’ll be able to stop your pattern of behaviour to control and harm the person you’re in an intimate relationship with.”

Domestic violence victims are more vulnerable than most other victims of crime, especially if they live with their abuser and have no means of escape.

Women's Aid Organisation (WAO) reports that with the current MCO, “even survivors who are typically able to maintain some level of independence and separation from their abuser are facing increased danger from close proximity and economic uncertainty.”

Already, there has been a spike in reports of domestic violence around the world as cities have been placed under some version or other of a lockdown. In Malaysia, WAO has already reported a 44 percent increase in hotline calls and WhatsApp enquiries from February to March.

Hence, the increasing concern about the impact of an extended MCO on domestic violence victims. The New York Times, for example, reported one phone call to the US National Violence Hotline where a woman described how her partner had tried to strangle her. But because of Covid-19, she feared to leave the home to go to the hospital. With no way of escaping, what do you imagine happens to victims of domestic violence?

Do you imagine that lifting up a prayer for a happy family is just the thing that’s needed to keep victims safe?

On April 6, United Nations secretary-general António Guterres tweeted: “Many women under lockdown for #COVID19 face violence where they should be safest: in their own homes. I urge all governments to put women’s safety first as they respond to the pandemic.”

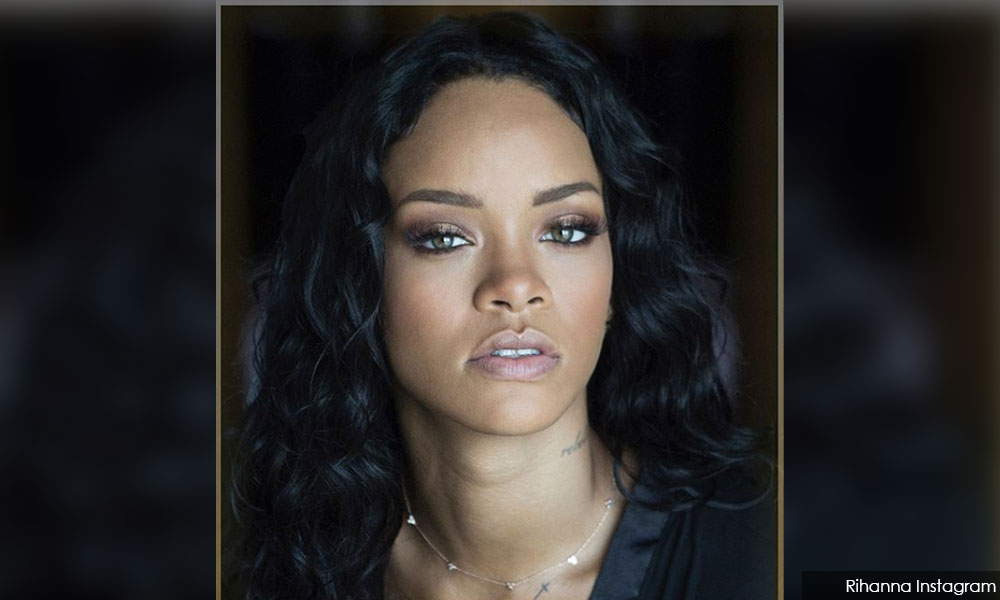

Even the singer Rihanna (photo), who is not an elected representative, has acted decisively to provide protection to women in Los Angeles. As a survivor herself, she understands the high risk to life that women in abusive relationships face.

Thankfully for the ministry here in Malaysia, it doesn’t actually need to think too much about how to put women’s safety first. WAO has already provided six clear steps for how this backdoor government can do that. But instead of taking on board WAO’s recommendations, what we have is useless advice from the deputy women’s minister.

At the end of her video, Siti Zailah declares with confidence that her tips should assure Malaysians that this is a government that cares for the citizens.

Unfortunately, Siti Zailah’s message is anything but an assurance. Instead, everything about it lets us know that this deputy minister is unfit and should be sacked. Indeed, domestic violence victims and survivors already know that.

Sadly, Siti Zailah and this government, I suspect, will continue to delude themselves.

JACQUELINE ANN SURIN is an online trainer and facilitator, a Drama@Work consultant, and a leadership coach. She was an award-winning columnist, a journalist for 20 years, and the co-founder of The Nut Graph before switching careers. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.