Enduring physical beatings is just one aspect of the difficult working conditions faced by many Nepali security guards in Malaysia, say migrant rights activists.

Such conditions include 12-hour working days, unpaid overtime wages, limited toilet breaks and being restricted from reporting abuse.

This has led to questions on whether there is a causal link between their working environment, medical problems and high death rate.

In 2016, at least 386 Nepali workers were reported to have died in Malaysia.

In 2018, the death toll was 322.

The Nepali embassy said alcohol abuse and brawls accounted for the bulk (198) of the 2018 deaths, while other top causes included suicide (43) and diseases like tuberculosis, liver ailments and dengue (39). A condition that health experts call Sudden Unexpected Death Syndrome (Suds), said to be linked to heart attacks, has also been cited as a cause of death.

In the latest data from the Nepal government’s Labour Migration Report, security guards made up about a fifth (20.6 percent) of the 382,651-strong Nepali workforce in Malaysia in 2018. Most (73.4 percent) worked in the manufacturing sector.

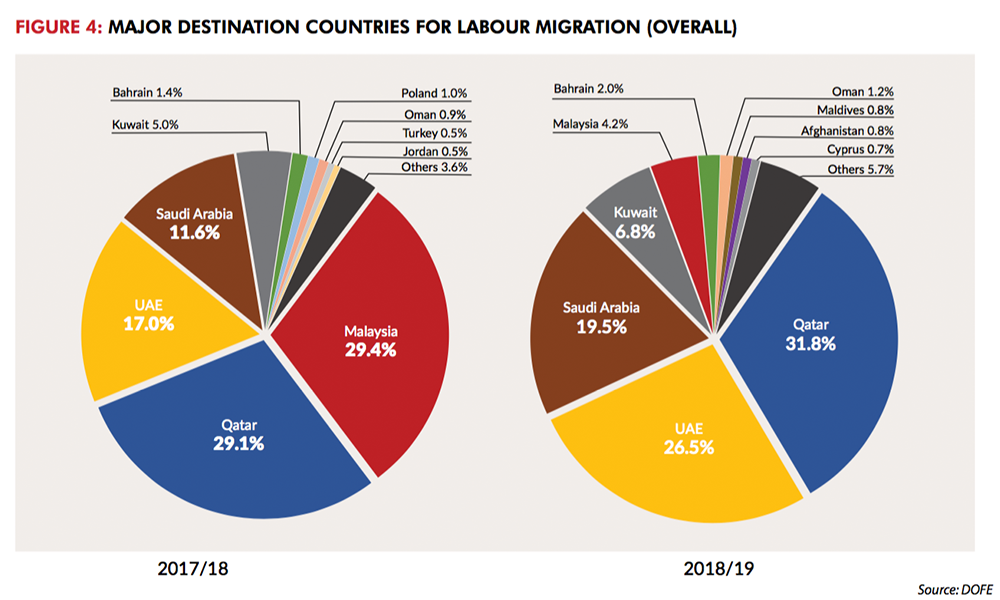

Published by the Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security of the government of Nepal, the report stated that Malaysia had traditionally been among the top five most popular destinations for Nepali workers along with Qatar, UAE, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait.

A sharp drop in Nepali workers in 2018/2019, it explained, was because deployment only resumed in Sept 2019 after both countries resolved technical issues with their bilateral memorandum of understanding.

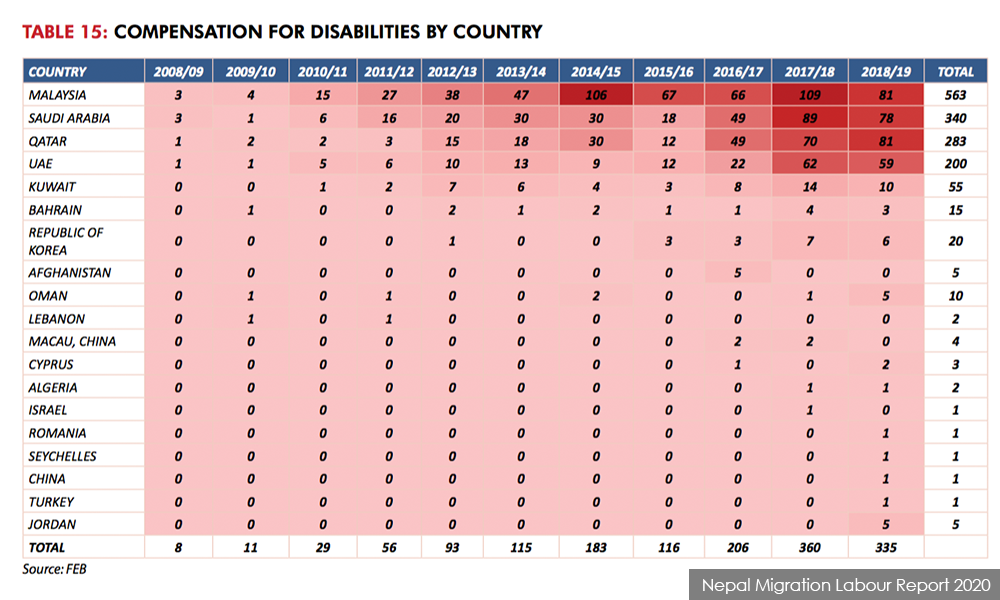

From 2008/2009 to 2018/2019, the data also showed Nepali workers returning from Malaysia made the highest number of disability claims - 563 in total. Qatar, UAE, Saudi Arabia and especially Kuwait recorded far fewer claims.

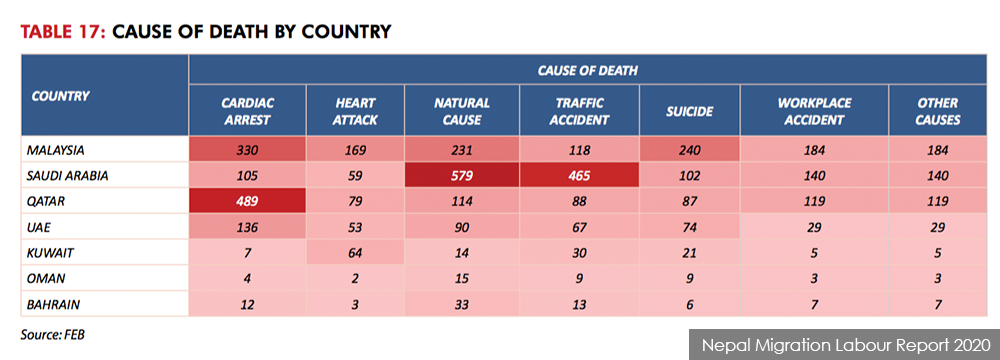

Malaysia again topped the list with a total of 1,456 compensation claims made by the families of deceased migrant workers across the same 10-year period. The top three causes of death listed were cardiac arrest (330), suicide (240) and unspecified “natural causes” (231).

Beatings ‘common’

According to Selangor Anti-Human Trafficking Council (Mapmas) member Abdul Aziz Ismail, adverse working conditions could be a factor for health problems and deaths among Nepali migrant workers, especially security guards.

What perpetuates these conditions, he said, is an environment that allows security companies impunity from abuse, exploitation and breach of contract.

In his experience dealing with more than 30 cases involving foreign security guards, he learned that the direct management of these guards was often subcontracted to a third party.

It was “common”, he said, for these third-party supervisors to employ physical assault to silence guards from raising questions, lodging complaints or making requests.

These are requests like taking leave or being paid for overtime work at a rate stated in their employment contracts.

“It indirectly gives them (third-party firms) the authority to manage according to what they want, without any liability by the company.

“So the company always gets away with it,” Aziz said.

Adrian Pereira from migrant rights NGO North-South Initiative and Tenaganita’s Glorene Das also observed that beatings were common.

“The video that is viral now is not the first time we have seen such a video of Nepali guards being beaten,” Pereira said.

Unpaid overtime, few toilet breaks

According to Aziz, supervisors are reluctant to pay workers more or employ extra workers for different shifts as this would raise costs.

By not commensurating them for the total hours worked, he argued that this constituted an unlawful deduction of salaries.

The Nepal government states a list of conditions in its standard contract for Malaysian employers who want to employ Nepali workers.

They are supposed to work eight-hour shifts for six days a week.

Workers are accorded a minimum of eight days annual leave, 14 days sick leave and 60 days of leave if they are hospitalised per year.

When he worked in Malaysia from 2016 to 2019, former security guard Santosh Sapkota said he often worked 12-hour days for a month without any breaks.

He told Malaysiakini he was physically assaulted when he requested for a one-day leave, and later hospitalised when he was beaten a second time, allegedly because he had complained to the Nepali embassy about the first incident.

Sapkota is now taking his case up with the Nepali government as well as its embassy in Malaysia.

Meanwhile, in a UK study published in the Nepal Journal of Epidemiology last year, Nepali migrant workers told researchers that 16-hour workdays were “normal”.

“Nepali migrants working as a security guard often complain that they are just allowed to use the toilet twice a day because employers do not have a replacement guard due to which they drink less amount of water,” the Bournemouth University researchers also said.

Other transgressions Aziz has come across include making workers pay for their own lodgings when security companies were supposed to provide this for free as per their contracts.

He said Nepali guards put up with such working conditions because they are threatened with the prospect of becoming undocumented if they raise any objections.

Plus, security companies or third-party supervisors sometimes unlawfully hold on to employee passports.

Without identification documents, guards are prevented from being able to lodge police reports if they are assaulted.

“They put pressure (on the guards) so that it gives the impression that you can’t run away.

“And if you go to the authorities, your (work) permit will be terminated,” Aziz explained.

Recently, Bangladeshi migrant worker Md Rayhan Kabir had his work permit revoked after he spoke to international broadcaster Al Jazeera about the mistreatment of migrant workers by Malaysian authorities during the movement control order period.

He has since been arrested, and it has been announced that he will be deported.

Debt bondage

Another reason why guards endure the mistreatment is that many are trapped in debt even before they begin earning an income.

Despite no mention of it in their employment contracts, Aziz said Nepali security guards also pay recruitment agencies between RM7,000 to RM9,000 in “placement fees” to secure jobs in Malaysia.

Meanwhile, they earn between RM1,200 to RM1,800 a month.

Guards, often the breadwinners of their families, need to resolve these debts before they can send any money home.

“By needing to recover that and pay the debt, indirectly they are under debt bondage when they work here,” Aziz remarked.

As for the use of third-party supervisors, the seasoned activist believed it was an industry-wide practice.

“This is my experience, they (security companies) are almost the same.

“If those that are quite established can do it, you think the smaller ones don’t have financial problems? They do the same thing,” he said.

Outsourced to other sectors

The use of these third-party firms also enabled Nepali workers to be surreptitiously “outsourced” to sectors different from what they were approved for.

This is despite Nepali migrant workers in Malaysia being contractually not permitted to change their employment during the contract period.

Glorene shared that she had come across such cases of "outsourcing".

"Where Nepali workers are concerned, we have found that many were brought in as plantation workers, then outsourced to do security guard work.

“They are not informed (that it's illegal), or the agents tell them it's common.

"So there is a lack of access to justice and remedies at the end of the day," she told Malaysiakini.

Nepali workers are presently employed in the manufacturing, plantation and private security sectors in Malaysia.

Human Resources Deputy Minister Awang Hashim recently revealed plans to restrict migrant workers to the construction, agriculture and plantation sectors to enable more local labour participation due to the Covid-19 pandemic. It is not known if the private security sector will be affected.

Aziz, meanwhile, said he encountered cases where firms would take in more migrant workers than they needed.

These firms, usually in sectors that were allowed a certain quota of migrant workers, then employ third-party supervisors to “deploy” excess workers to other sectors and companies.

In turn, these supervisors earned a commission for each worker they managed to place.

He shared one example where a Nepali worker was brought into Malaysia to work in a garment factory in Perak but was later found to have become a security guard in Kuala Lumpur.

Enforce better working conditions

All activists Malaysiakini spoke to urged for more stringent enforcement by the human resources ministry and Immigration department to penalise companies for contractual violations and human rights abuses committed against Nepali guards.

Aziz also pointed out concerns about corruption in the management of migrant workers.

Back in 2018, Malaysiakini and the Centre for Investigative Journalism Nepal detailed a network of companies and government agencies in both Malaysia and Nepal that illegally collected some RM185 million from 600,000 people between Sept 2013 and April 2018.

Pereira, meanwhile, urged for more transparency.

"We need more regulations and more inspections to supervise the working conditions of our security guards [...] It's not even clear how the Labour Department does inspections and monitoring for this sort of sector.

"We don't have the data so we are running around in circles and yet it's clear that this sector really needs reform," Pereira said.

The Nepal Journal of Epidemiology study also proposed better record-keeping and more thorough post-mortems of Nepali migrant worker deaths.

This, they said, would enable a better understanding of why a Nepali migrant worker reportedly dies every day in Malaysia. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.