The last few years have been years of confusion in Malaysian politics. This is strange because the results of the 14th general election (GE14) in May 2018, with Pakatan Harapan's victory over Barisan Nasional, ought to have ushered in a period of fog-dispelling clarity.

This clarity inhered in the popular perception that the country could not be run the way BN's main component, Umno, had been governing it.

A plurality of Malaysia's voters endorsed that sentiment at the ballot box, enabling the citizenry to wake up on May 10, 2018, to the expectation the morrow would usher in a raft of changes.

Essentially, these reforms would have to be to the institutional life of the country that would re-steer it towards fulfilment of the promises envisaged by the Merdeka Proclamation and the 1957 Federal Constitution.

Radical deviation from these bearings was what brought the country to the sorry pass it was before GE14. There had to be change – reformasi, as the Harapan catchphrase had it.

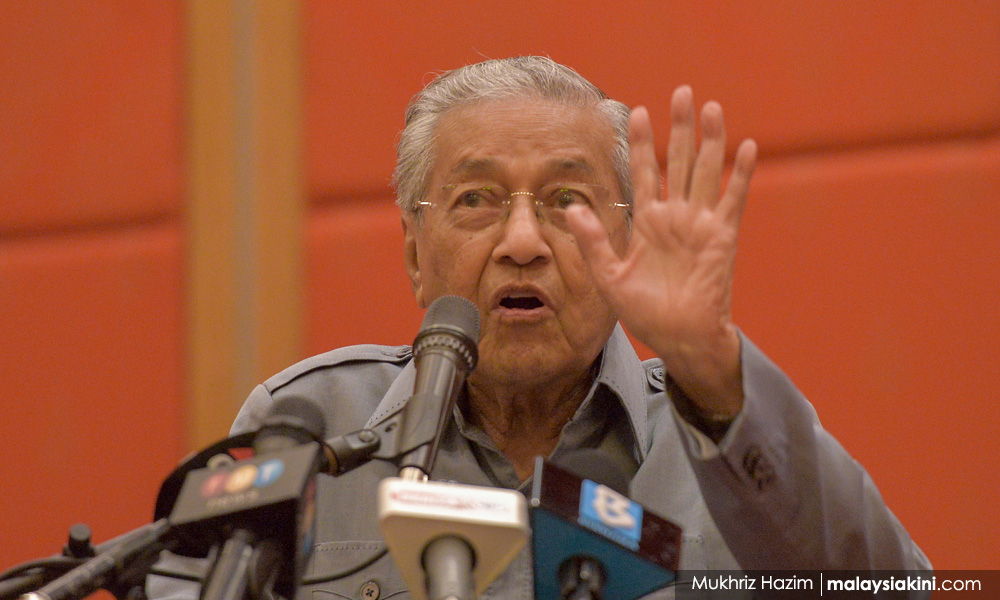

Though change was initiated under Harapan, it was not swift nor deep enough. This was because, in retrospect, Harapan's drum major, Dr Mahathir Mohamad, was not only a tepid believer in reform, he was its insidious subverter.

Neither the DAP, PKR nor Amanah could tug at the head honcho's sleeve to tell him he was going out of bounds, and that he had to get back on course.

Three of the four components of Harapan had their reasons to be bemused by Mahathir. DAP was obviously grateful to Mahathir because the Attorney-General's Chambers was not going to proceed with corruption charges against its secretary-general, Lim Guan Eng.

Amanah, with a paltry 11 seats in Parliament, had been rewarded by Mahathir with disproportionately generous representation in the cabinet, rendering it somnolent and glad.

As for PKR, it was left puzzling over ways to get Mahathir to stick to his promise that his premiership would be an interim one, with a handover to PKR president Anwar Ibrahim sooner rather than later.

Accentuating PKR's bewilderment was a revolt that a Mahathir-stoked Azmin Ali was generating. With Mahathir's prevarications, PKR's restiveness, DAP's bafflement and Amanah's bemusement, all playing against the roiling backdrop of the khat issue, Malay Dignity Congress, Zakir Naik's insolent provocations, and the detention of 12 supposed LTTE sympathisers, a witches' brew of tumult was fomenting.

Matters were so dishevelled and confused that when a Muhyiddin Yassin-led Bersatu left Harapan in late February 2020 to link up with a cohort composed of MPs from Umno, PAS, Gabongan Parti Sarawak, outliers from Sabah, and defectors from PKR, there was some relief that at least someone – in this case Muhyiddin – was taking charge of the country as head of a new coalition.

After a protracted period of confusion, at least someone was seen to be taking charge though the process of the takeover smacked of illegitimacy.

However, after starting out well, especially against the Covid-19 contagion, Muhyiddin, too, lost his way, amid criticism that the Malay-Muslim government he led was an unviable proposition, given the racial and religious diversity of the population.

In the ensuing hubbub, Mahathir seemed more interested in explaining why he had abruptly resigned as prime minister without first consulting his coalition partners than in suggesting an alternative course to the one Muhyiddin was taking.

Meanwhile, Anwar continued to be engrossed with the numbers game, to wit, how many MPs he had that would support a Harapan-Plus government he proposed to lead as replacement for Muhyiddin's.

No doubt, last September when the Sabah state election campaign was on, Warisan's Shafie Apdal acted and spoke like a leader who harboured an inclusive vision for the country.

First among equals

But no other leader than Umno deputy president, Mohamad Hasan, has done more – in the period of the realisation that Muhyiddin's premiership was failing on account of its narrowness – to articulate a political vision that Malaysians can support.

In the last nine months at least, he has espoused the view that his party should return to its qualities of old. These are that while Umno is at its core sectarian in its advocacy of the Malays, it nurtures a broader concern for the whole country which it recognises as racially and religiously diverse.

That while Umno will want itself and the people it represents to be primary in all matters, it ought to eschew a stultifying dominance that will harm itself and the country.

In other words, Malays and Umno must be first among equals, primary but not hegemonic, a banyan tree that provides shade, but under which others can grow.

He is just about the only important leader of a major party to enunciate this theme often and consistently.

In an interview with the web news portal Free Malaysia Today, he amplified the theme, on the eve of a crucial Umno conclave this weekend that will decide its future.

How has this man who before GE14 suggested to the state youth chapter of his party that they overturn tables in coffeeshops whenever they overhear anti-Umno talk come to voice the most inclusivist vision of a major Malaysian leader is a matter for speculation.

But right now, it is a substantive vision he has articulated and he has stayed on the theme for some time. It is a supportable vision, given that the Malays are interested in asserting Malay political primacy and may be amenable - following three years of Umno's estrangement from federal dominance - to deflection away from being overbearing.

Would Tok Mat, as he is popularly called, after having obviously recanted his regrettable advice to his youth wing, be able to persuade Umno to slough off its once domineering self and assume a new old skin, that of political overseer but not hegemon? - Mkini

TERENCE NETTO has been a journalist for more than four decades.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.