HISTORY: TOLD AS IT IS | After 130 years of Portuguese rule (1511-1641) and another 183 years of Dutch rule (1641-1824), it was time for the British to take control of the Malay peninsula beginning with the occupation of Penang island in 1786.

However, unlike the Portuguese and the Dutch, the British colonial era left the greatest enduring legacy. From the creation of a multicultural society to the creation of Malaysia as a political state, British colonialism dictated how the country would be managed even after independence.

The more far-reaching legacy is that of economic inequality. When CA Vlieland, the Superintendent of the Malayan Census in 1931, used the terms ‘Old Malaya’ to refer to the northern Unfederated Malay States (Kedah, Perlis, Kelantan, and Terengganu) and ‘New Malaya’ to refer to the west coast Federated Malay States (Perak, Negeri Sembilan, Selangor, and Pahang), there were dividing lines being drawn.

The British evidently focused on developing the economy on the west coast, whereas the east coast remained less developed, if not underdeveloped.

From 1957, independent Malaya inherited this disparity, which persists to this day. A review of colonial Malaya’s economic history reveals how and why this has unfolded.

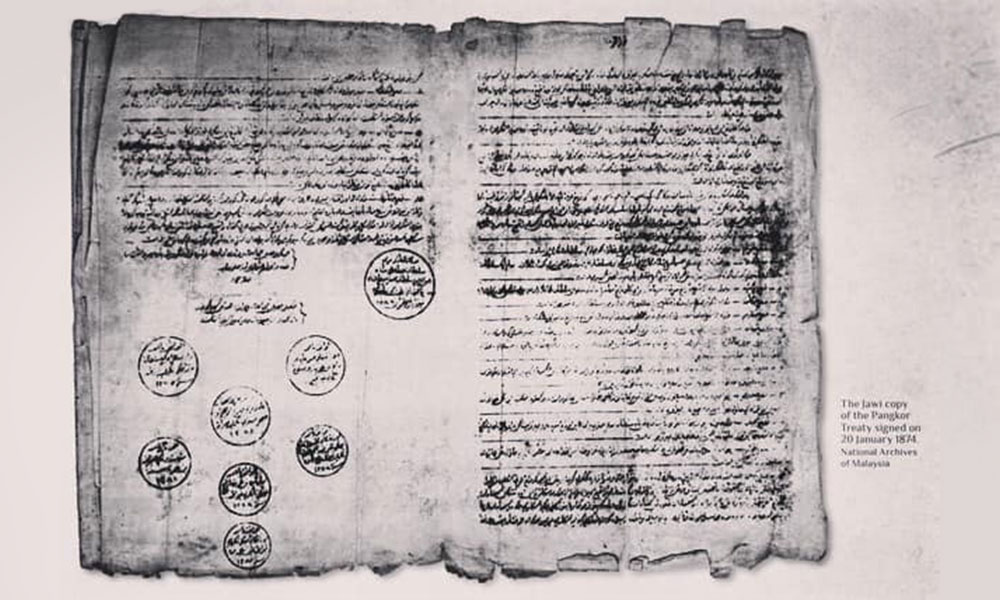

After the Pangkor Agreement of 1874, British intervention in Perak was followed by similar action in the rest of the western states.

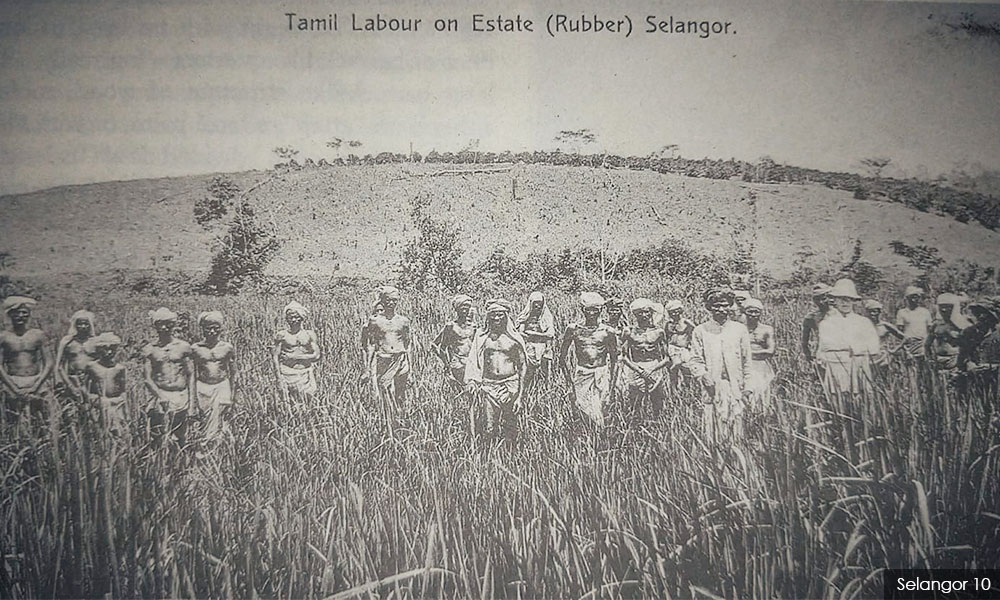

Under a Residential System, a period of rapid economic exploitation ensued, profiting on the flow of capital into these states. Mining and agriculture were the principal focus of the colonial administration, which adopted a laissez-faire approach in order to stimulate greater capital investment by the Europeans and the Chinese.

As a result, substantial revenue was generated, particularly once a liberal land policy was implemented after 1900.

Around the same time, the northern economy began to dwindle. Between 1870 and 1900, sugar growing, for example, was a highly capitalised activity in southern Province Wellesley.

In the 1900s, the base shifted to the neighbouring Perak district of Krian, and by 1914, the sugar industry of north-west Malaya had all but vanished.

Coffee cultivation was also a major activity in Perak as early as 1896, with significant acreage in Selangor and Negeri Sembilan. In the mining sector, the Federated Malay States exported the bulk of Malaya’s tin export between 1911 and 1929.

The most illustrious history of all was, of course, that of rubber planting. By 1906, rubber had been grown on 80 percent of the total land area of Selangor, Perak and Negeri Sembilan.

Since the economy of British Malaya was centred on the west coast, railway lines and roads were built mostly there. The increased use of automobiles after 1902 accelerated the road development plan.

Although there was a road stretching from Singapore to Perlis by 1928 and a well-developed road network in other west coast states, Terengganu remained without a road and Kelantan had only a few roads.

Perlis was still underdeveloped and it needed a loan from the Straits Settlements to build its only trunk road. Even in the 1930s, there was no road connecting Pahang and Terengganu.

Even after independence, the situation remained mostly similar. The east coast Malay states continued to fall behind despite the adoption of the colonial Draft Development Plan 1950-55 and similar initiatives in independent Malaya, such as the First Malaya Plan 1956-60 and the Second Malaya Plan 1961-65.

To put it another way, the ‘Old Malaya’ persisted.

Today’s lopsided development

Four decades later, in 2007, the East Coast Economic Region (ECER) and Northern Corridor Economic Region (NCER) initiatives were announced - the first development plans designed particularly for the northern region.

The ECER covered Kelantan, Terengganu, Pahang and the Johor district of Mersing. Tourism, oil, gas and petrochemical industries, agriculture, and education were prioritised.

Meanwhile, the NCER focused on agriculture, industry, tourism and logistics in Perlis, Kedah, Penang and the northern Perak districts of Hulu Perak, Kerian, Kuala Kangsar as well as Larut-Matang-Selama.

During the launch of these programmes, then prime minister Abdullah Badawi decried the extent to which disparities persisted even after half a century of independence.

Clearly, the post-independence government had been pursuing a policy similar to that of the British in the past, which had neglected the east coast.

The heavy role of foreign advisers may have contributed to the negligence. The first Malaysian plans were drafted with the assistance of US professors Warren Hansbuger, VM Bernett, Dr D Snodgrass, HJ Bruton, and B Higgins.

Instead of focusing on rectifying the imbalances caused by the colonial economy, the government continued to protect international interests concentrated on the western states.

The government also inherited the colonial attitude of dividing modern from traditional sectors when in reality both sectors had strong structural links with one another. The Malaysian plans failed to address the root causes of poverty in the northern states. The emphasis was mostly on the importance of introducing capital and technology.

Clearly, British economic expansion in Malaya laid the groundwork for economic development throughout most of the west coast. However, it had also resulted in a significant marginalisation of the east coast.

This resulted in what is best represented in terms of ‘Old’ and ‘New’ Malaya. The British were conscious of ensuring that the east coast remained the country’s rice bowl, expected to feed the west coast’s population.

Following independence, the concentration of economic activities on the peninsula’s west coast, as well as the accumulation of wealth in urban areas, led to unequal development. Numerous attempts were nevertheless undertaken by the government to correct the imbalance.

The ECER and the NCER can be interpreted as an indirect admission of lopsided development and the persistence of colonial-minded ideology even after independence. - Mkini

SIVACHANDRALINGAM SUNDARA RAJA is an associate professor at the Universiti Malaya’s History Department. He is a well-known scholar in the field of Malaysian economic history, with numerous local and international research publications to his credit.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.