It has taken the Malaysian opposition seven straight election defeats (in four by-elections and three state elections) to realise they have a problem.

For the first time since the acrimonious backdoor coup of the “Sheraton Move” in February 2020, all the opposition parties have openly stated their wish to work together, through a coalition, electoral pact, or other arrangements, under one “Big Tent”.

In March 2022, Bersatu president and former prime minister Muhyiddin Yassin started holding meetings with Pejuang, the small party led by Dr Mahathir Mohamad, and PKR, the de facto leader of the largest opposition bloc, Pakatan Harapan.

The other component parties of Harapan, Amanah and DAP, had also talked about a “Big Tent” approach to unite all opposition parties to defeat the incumbent BN that has seemingly regained its dominance.

The “Big Tent” strategy relies on a simple political concept: that the root cause of any incumbent’s electoral success is a disunited opposition. To defeat longstanding powerful regimes, like the stunning successes in Kenya in 2002, Ukraine in 2004, India in 2014, and Mexico in 2000, the opposition must work together.

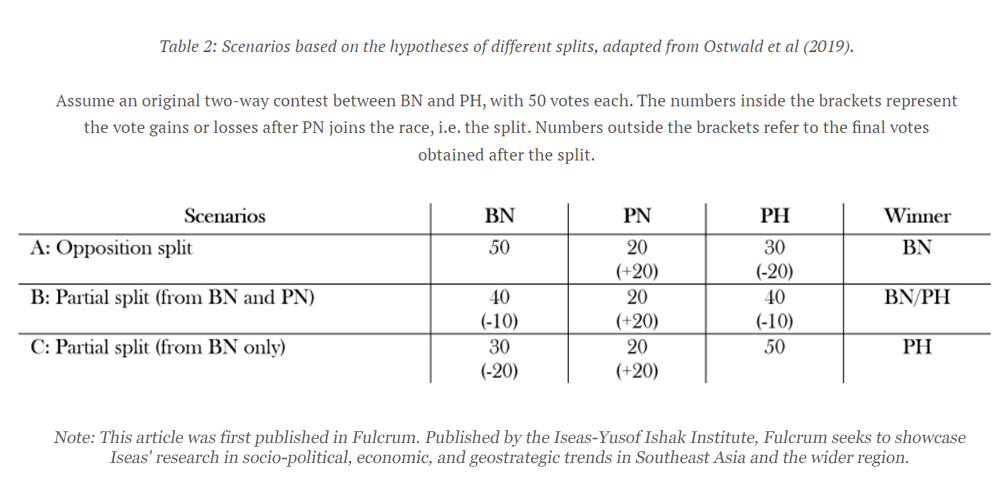

A 2019 study by political scientists Ostwald, Shuller and Chong called this the “opposition split hypothesis”. A high number of opposition parties contesting in an election would split the opposition votes, thus making it easier for the incumbent (like BN in Malaysia) to clinch a victory with lower winning thresholds.

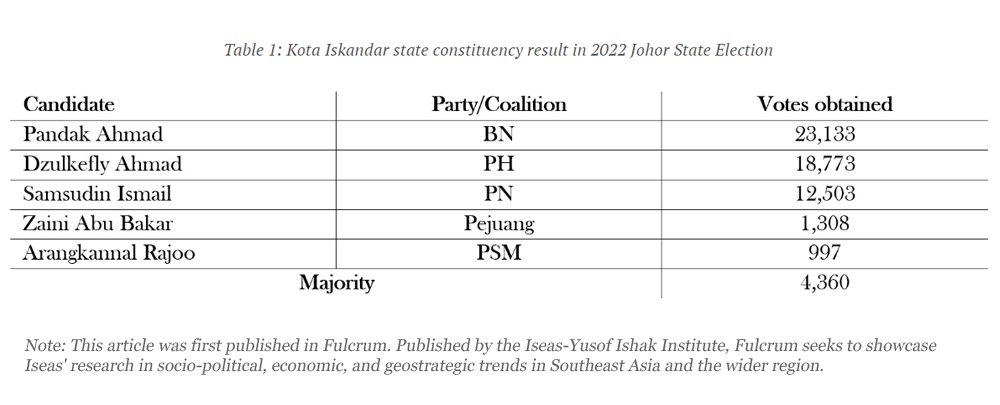

Using the recent 2022 Johor state election as an example, if the opposition had used a “Big Tent” strategy, it would have saved seats like Kota Iskandar. The Harapan candidate, Dzulkefly Ahmad, had won by a commanding majority of 14,543 votes nearly 4 years ago, but the result in 2022 was vastly different:

This poor showing in 2022 makes the argument for an opposition “Big Tent” irresistible. Combining all the non-BN votes would have allowed the opposition to win the seat by 10,448 votes in a one-on-one contest. If the opposition had used this strategy for the rest of the seats, it would have gained another 19 seats, denying BN its landslide victory.

GE14 a poor ‘Big Tent’ example

Every opposition leader who mentioned the “Big Tent” concept pointed to the historic opposition victory in GE14 that ended BN’s 61-year hegemony. They claimed that Harapan won because it was willing to work with its arch-enemy, Mahathir, then the chairperson of Bersatu, and Mohd Shafie Apdal, from Sabah-based Warisan.

The only problem, however, is that GE14 is a poor example of how to succeed using a “Big Tent” strategy. GE14 was Malaysia’s most competitive election, where the largest coalitions had nationwide three-cornered fights. It was also an election where the Malay votes, representing the majority of the electorate, were split in three ways, with each coalition gaining a vote-share between 25 to 40 percent.

If the opposition split hypothesis held true, BN would have won handsomely in GE14 and Harapan would not have ushered in Malaysia’s first power turnover. GE14 showed that there were other ways for votes to be split.

To illustrate this, let us take one imagined constituency of 100 votes with a three-cornered fight between BN, Perikatan Nasional (PN), and Harapan, with PN as the newly introduced third party:

Scenario A is the classic opposition split scenario where a third party, PN, would split Harapan’s votes, thus making BN’s victory a virtual certainty. However, this assumes that BN’s voters are a monolithic bloc when, in fact, they likely are on a spectrum from borderline-BN supporters to hardcore-BN supporters.

Scenarios B and C are more realistic. In Scenario B, where PN absorbs votes from both BN and Harapan, the latter two still stand a chance to win on a thin majority depending on how many votes PN absorbs. In Scenario C, where PN splits only BN’s votes, this secures a Harapan victory.

‘Big Tent’ the last thing Harapan should do

In GE14, something akin to Scenario C happened. PAS absorbed the weak BN supporters’ votes dramatically because of the perceived Umno-PAS similarities in their Malay-Muslim credentials (with Umno as leader of BN) and public resentment against Najib’s corruption allegations.

Instead of taking votes away from Harapan, PAS took rural, conservative Malay votes from BN. On top of that, Harapan maximised the support from its voter base of urban non-Malays. In this way, a partial split instead of a full opposition split was the principal cause for BN’s surprise defeat in GE14.

The best representation of a “Big Tent” approach was actually GE13 and not GE14, where the opposition formed an unlikely alliance of PKR, DAP, and PAS: Pakatan Rakyat (PR). This set up a nationwide straight fight.

If the opposition split hypothesis held, PR should have walked away with at least 107 seats, or 189 seats in the best-case scenario. Instead, they won only 89 seats - 23 seats shy of taking government.

To win, Harapn should maintain a professional distance from a coalition like PN, because the latter’s ability to split BN’s votes is favourable to Harapan. Joining forces under a “Big Tent” is the last thing it should do.

In Malaysia, the opposition split hypothesis does not hold, making the opposition’s calls for a “Big Tent” strategy a misplaced fantasy. - Mkini

JAMES CHAI is a visiting fellow at the Iseas-Yusof Ishak Institute. He also blogs at www.jameschai.com.my and can be reached at jameschai.mpuk@gmail.com.

This article was first published in Fulcrum. Published by the Iseas-Yusof Ishak Institute, Fulcrum seeks to showcase Iseas' research in socio-political, economic, and geostrategic trends in Southeast Asia and the wider region.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.