As Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim marks his first year of office there are a range of opinions from sycophantic public-relations pieces to those more critical.

Here, in two pieces, I focus on his one-year record in office and in a subsequent article on how Malaysian politics is changing.

I argue that much of the positive changes taking place are in spite of Anwar’s leadership, rather than because of it.

At best, Anwar’s performance is mixed; he has succeeded in staying in power but at serious costs to his credibility and at the expense of the expectations and hopes of his political base.

If Anwar’s government continues along the path of the past year, a much-needed opportunity to strengthen Malaysia could be lost.

A ‘mixed-ani’ record

Of those who have criticised Anwar’s government, there are common themes – a lack (and even backtracking) of reform, embracing conservative Islamisation, myopic attention on his personal popularity rather than his government’s performance, a lack of clear messaging and focused priorities and lacklustre deliverables, especially on the economy.

Anwar is portrayed as a talker, over-promising and flitting from one issue to another, as he frequently travels abroad without adequate attention to domestic issues.

Many contend the important ministry he heads (finance) is being neglected. Two budgets on, the government has yet to instil strong confidence in his (and his uneven cabinet’s) stewardship of the economy.

Unlike recent governments, however, this year has seen some substantive policy outputs; new plans on industry (Industrial Master Plan 2030) and energy (National Energy Transition Roadmap) and a more careful mid-term review of the 12th Malaysia Plan.

Landmark legislation on the death penalty, decriminalising suicide, child protection, housewife social security and the recognition of trade unions were passed.

Importantly, these laws were not initiated by the Anwar government - much of the credit for these pieces of legislation, ironically, should be given to the Pakatan Harapan government led by Dr Mahathir Mohamad. Yet, without the support of key individuals in the Anwar government, they would not have been passed.

Arguably, the two legislative measures that can best be credited to Anwar’s administration are a rather superficial financial integrity bill regulating macroeconomic policy and debt (as national debt increases) and a significant opening of public data, an initiative spearheaded by Economy Rafizi Ramli.

More quietly, there has been a modest streamlining of governance, improvements in efficiency and greater cooperation among ministries. This has come despite strong resistance from the bureaucracy who overwhelmingly did not vote for the current government.

Legislatively, what has captured attention are both the dangerous bills and amendments introduced - the absolutely shameful legalisation of vaping and a callous expansion of the statelessness of children in amendments over citizenship.

The latter bill has held back promised citizenship to children born of Malaysian mothers abroad, (needlessly) causing further trauma.

What has characterised these failures has been a lack of compassion on the part of the Anwar government, the total opposite of what his branded Madani government claims to be about.

Faustian bargain: Power for principles

It is these sorts of ironic contradictions that have characterised Anwar’s year in office.

Broadly, Anwar’s greatest achievement is political survival, in his career as a whole and in office this past year.

As prime minister, he has stayed in power bringing a semblance of stability to local politics after five difficult years of instability and political uncertainty. This achievement should not be underestimated.

Honing his bargaining skill, he cobbled together a two-thirds coalition in Parliament and the coalition has stayed together, despite considerable quiet dissatisfaction among many inside the government.

It has come at a cost of continued political patronage in the management of government bodies, with “business as usual” mentality continuing.

Unlike the previous Pakatan Harapan-led government, where internal differences were on display, these have been minimised publicly in what has evolved into working elite cooperation among previous political opponents.

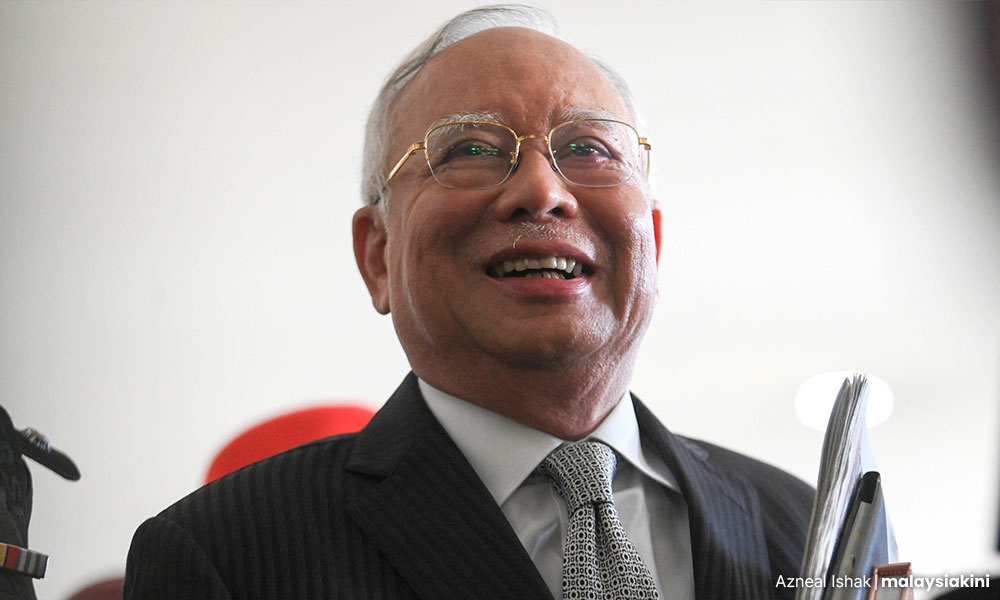

What is surprising (for some) is how well Pakatan Harapan parties have worked with Umno and Borneo parties. The only issue that has been publicly grated is the repeated calls to pardon convicted former prime minister, Najib Tun Razak.

At the elite level, Anwar’s support has increased, as he has reached into the opposition for support, building on splits within Bersatu. In opting to embrace opposition defectors in recent months, he has enhanced a destabilising drive in Malaysian politics, an unnecessary risk.

Yet, what is clear is that the mode of political insecurity runs deep. Like other figures in the opposition who assumed office, the psyche of uncertainty as an opposition politician is hard to break. Here is an ironic rub: despite a strong majority not in need of the numbers, Anwar is still searching for support.

This is not the only contrary dynamic; the desire for power has led to a loss of principles. Anwar would not be in power at all without those who supported reform. This has gone by the wayside, shattered by the decision to withdraw charges of his political ally and deputy prime minister.

Every word (as there is little action) on corruption, lacks credibility. Little has been done to build democratic institutions in his first year of office, from media freedom to electoral reform.

This concern with abandoning reform has spilt over to other issues, with Anwar facing a growing trust deficit. Many are questioning what Anwar stands for. This questioning goes beyond the man, extending into his government as a range of manifesto promises are now being disregarded in power.

In short, in the Faustian style, the bargain for power has left reform behind. Some in the public pragmatically accept this dynamic, while others are less forgiving.

Persistence of Anwar’s Umno past

While Anwar’s electoral support was tied to giving him “time” to address current issues and strengthen Malaysia for the future, his first year in office shows he has wrestled with leaving his past behind, especially his time in Umno.

Anwar continues his Islamisation focus like he did when he was first in office. While some believe this is politicking to garner Malay support, others believe he has returned to his days as a student activist Islamist.

He is caught - his efforts are not bringing him greater support among Malays. At the same time, he is losing support among non-Muslims, especially in Borneo.

There is growing concern that Anwar has returned to his 1990s deputy prime minister pattern of further political institutionalisation of religion, dividing Malaysian society further.

Ironically, the more Anwar embraces and normalises an Islamist agenda, the more he normalises the option for an Islamist party to govern nationally.

His support, especially in the August six state elections, was anchored on being a more moderate alternative. Many see the difference among the alternatives narrowing.

Perhaps, the biggest irony is the role that Mahathir has played in Anwar’s first year. So many of the practices of Mahathir politics, notably attacks on opposition leaders and denial to opposition voters of development constituency funds, have resurfaced in Anwar’s first year.

Despite decades of challenging Mahathir, many of the lessons Anwar learned from him seemed to have remained, including building and personalising power around the prime minister rather than through a strong governance team.

Both men also show that the acrimony of the past lives on, now in new court cases.

A needed pivot

The key challenge for the Anwar government ahead is not to hold onto the past, but to concentrate on moving forward.

In order to do this, the government and governance need to be about Malaysia, her future, rather than about Anwar. There needs to be a clear plan and priorities for the coming year, with a stronger cabinet to implement policies.

It is important to recognise that the window for implementing policies is narrow; after a year, public support for the Harapan government of 2018-2020 eroded rapidly.

For Anwar’s government, there is still time to pivot. If they continue as they have done, holding on and in a holding pattern - they risk facing similar erosion of public support ahead.

BRIDGET WELSH is an honourary research associate of the University of Nottingham’s Asia Research Institute, a senior research associate at Hu Fu Center for East Asia Democratic Studies, and a senior associate fellow at The Habibie Centre. Her writings can be found at bridgetwelsh.com.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.