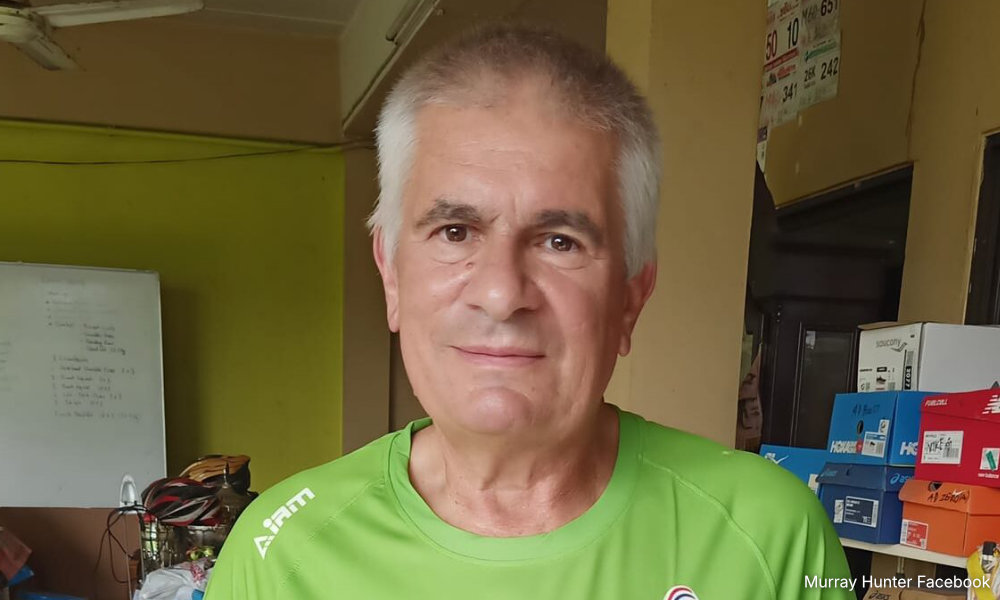

The arrest of Australian academic and political commentator, Murray Hunter, in Thailand is not an isolated event.

On Sept 29, 2025, Hunter was detained at Bangkok’s Suvarnabhumi Airport as he prepared to board a flight to Hong Kong. He denied doing anything wrong in Thailand. He has since been released on bail, pending a November hearing.

His detention serves as a warning shot to Malaysian citizens, to Thailand’s judiciary, to the MCMC, and to the wider world watching Malaysia’s democratic backslide.

More importantly, it shows a failure of leadership in the Madani administration’s system of governance.

The overreaction by the MCMC to Hunter’s writings about Malaysian institutions and powerful individuals has now morphed into something that threatens the fabric of Malaysian democracy.

Shock waves are sent around the world because Malaysia, once considered a beacon of democracy, is now seen as an autocratic banana republic.

Bringing countries into disrepute

Hunter worked as a university lecturer and consultant, and lived in Malaysia for several decades before relocating to Thailand. He knows Malaysia very well and is privy to the workings of the people in industry and government.

Although he has not committed any crime, MCMC’s relentless pursuit of Hunter over the border has now dragged the Thai authorities into disrepute.

Hunter’s arrest has shown that anyone who criticises another country now faces an uncertain future in Thailand, and perhaps, in Asean.

Reporters, columnists, political commentators, or ordinary citizens who care about their respective nations and dare to speak out now feel threatened because what they write has wider implications.

How will companies, potential investors, tourists, or foreigners who have made Thailand their adopted home now feel when even an academic like Hunter can be arrested?

‘Ask MCMC’

Communications Minister Fahmi Fadzil was asked by reporters about Hunter’s allegation that the MCMC had initiated his arrest in Thailand. Fahmi said that he did not know and told them to ask the MCMC.

The role of the MCMC is within Fahmi’s purview. If he, the minister, does not know, then who does? Who’s in charge of his ministry? It appears that the left hand does not know what the right hand is doing.

Does Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim know that the MCMC has caused serious damage to the reputation of not just the ministry, but the Madani cabinet and Malaysia?

The warning to Malaysian citizens is to “Stay Silent”. This message is chilling. If a foreigner can be pursued abroad for writing critically about Malaysian politics, what hope do local journalists, bloggers or TikTok users have?

Why is Thailand cooperating?

This case joins a growing list of arrests. Malaysiakini’s B Nantha Kumar was arrested in February 2025. Ordinary citizens have also been hauled in for their comments about race, religion or royalty.

The space for dissent is being squeezed smaller, and censorship is no longer just prudent; it is becoming inevitable.

By executing this warrant, Thailand risks its image of a neutral arbiter of justice. Now, it’s seen more like an extension of another government’s reach.

Asean cooperation is designed to fight serious crime, and not to police speech. Bangkok should ask whether it is comfortable being the stooge for Malaysia, outsourcing its political sensitivities.

Many Malaysians also wonder whether the MCMC operates without any checks. It is meant to regulate, not to intimidate.

Yet under the Madani administration, its powers to investigate and censor online content have expanded without transparency. Trust in regulatory fairness is undermined.

MCMC may have thought that Hunter’s arrest was pretty straightforward, but its rash decision has now opened a Pandora’s Box.

Media freedom in retreat

We are witnessing the retreat of media freedom in Malaysia. Criminal defamation already chills speech. Applied across borders, it becomes a weapon.

Hunter’s case fits a regional trend. In May, Malaysia deported a maid from Cambodia, who had criticised former Cambodian leaders.

Anwar claimed the deportation was to preserve bilateral relations within Asean. However, Malaysia showed double standards when the Indian government’s request for the extradition of its own national, the fugitive and controversial preacher, Zakir Naik, was declined.

Why did Malaysia agree to an Asean country’s request but reject the one made by a fellow Commonwealth member? The Malaysian government appears to selectively enforce laws to muzzle dissent.

The Madani government’s reform credibility is now under heavy scrutiny. Both Anwar and Fahmi once campaigned on reform and freedom. Now they preside over a state that punishes speech at home and appears to pursue critics abroad.

A perfect opportunity to show that the government values debate and due process has been missed. Instead, it reinforces the impression that Malaysia’s reform promises were mere campaign slogans, not governing principles.

Arresting Hunter has invited an international audience, which includes long queues of international reporters waiting to interview him. The MCMC should be proud that it has helped to shine the spotlight on Malaysia.

Fahmi’s lack of control of the MCMC undermines the country’s image as a moderate, rights-respecting democracy. Questions about Asean’s role in inadvertently aiding repression are currently being asked.

This reputational damage could carry real costs in diplomacy, trade and human rights forums. It also poses a serious impact on foreign investment, the tourism trade and normal bilateral relations.

This case is not just about one academic speaking out about Malaysia, because it is also about Malaysia exporting its domestic intolerance to foreign jurisdictions. - Mkini

MARIAM MOKHTAR is a defender of the truth, the admiral-general of the Green Bean Army, and the president of the Perak Liberation Organisation (PLO). Blog, X.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.