For many, the movement control order (MCO) is one full of stark choices, even life and death as people go hungry, being evicted and physically in pain.

Let’s start with their stories. Please meet the following people, full names withheld, who are based in the Klang Valley and facing difficult circumstances.

My name is Mrs CH. I am a 74-year-old Malaysian. I used to rent a hawker stall but sold it about five years ago. I do not have a regular pension, and I do not have children. My only sister passed away last year. I live in a small room in Kajang. I get by through working part-time in a restaurant. It is now closed. In my room, I have a mattress. No window. No kitchen. I use shared bathroom facilities without any privacy. Every day I wake up, my body is in pain. My joints hurt, but most of all, I am weak. I eat noodles when I can, as I can boil my kettle, but I have not eaten any protein, fruit or vegetables in a long time. I have run out of supply. My head hurts all the time. I feel dizzy. I don’t have the energy to move. I wait for someone to call me as I do not have credit on my phone to call anyone. I wait to see if someone will knock on my door with food.

My name is M. I am 27 years old. I am a university graduate but am now homeless. I am originally from Kelantan. I have lived on the streets for three years near Bukit Bintang. I am a drug addict. I go to the shelter for food. I want to stop using drugs, but do not know how to do so. I am confused. I am scared.

Meet Mr AD. We are a family of five – my wife, my three children, ages three, five and six, and myself. We live inside our car. We move around, parking our car near apartments at night. We cannot move far, as we need to save petrol. We shower in mosques or petrol stations. We access food through a network of friends, but cannot have a hot meal, as we do not have a kitchen or cooking facilities. We are refugees from Palestine and have been in Malaysia for five years. I have not been able to find work to feed or house my family. I lost the only part-time job I had at the start of the MCO period. It has been very hard living in a car.

Mrs E, living in Chow Kit, contacted an NGO worker on Tuesday at 4am. She was in a small 10 by 8 feet room with two children, ages 12 and 17. She had no food and money and RM8 in her wallet. Her daughter is sick. She is a house cleaner and cannot work. She is now a caregiver. An NGO provided some dry food but is still trying to find a way to get medical attention for her daughter.

Meet a refugee family of five, a husband Mr A, aged 46, his wife and three sons, ages from 12 to 17 years. Originally also from the Middle East, they live in a house for one and half years. The husband worked part-time,, and sometimes the children also found work. Their problems start in January when there was an intensification of the crackdown on migrants around Cyberjaya, limiting their opportunities to work. He rented a house for RM1,200 monthly. He was evicted on March 31. His community network was able to collect money to find his family temporary shelter, another house for RM1,000. The owner has given them two weeks to pay the deposit. He and his family get food from a food bank.

A technical school has closed during the lockdown in Puchong. There are 230 Malaysian students, largely from Sabah and Sarawak, stuck in their hostels. They do not have the funds to get home and are running out of money for food. They have reached out to local authorities who have informed them the food allocations have already been made for that area. They are reaching out further to the NGO communities.

I am Mrs IK, now 65 years old. I used to be a secretary working for a private company. I receive a small pension. It runs out every month, after two weeks. I go without food regularly. I try to eat every other day to get through the month. In this MCO period, I have been cutting back further as I do not know what will happen to my pension if something happens to the company.

Vignettes of the invisible – A social crisis

These experiences are only a microcosm of what is being experienced by many people. These individuals are across ethnicities, ages and come from different backgrounds. They are the elderly, single-mother/father households, children and disabled. They share a common feature – facing difficult hardships and in need of help.

Today, as Covid-19 hits hard, the biggest divide in Malaysia is one that cuts the society along class lines, with those that have the resources to survive and others who are not as fortunate. The MCO did not necessarily cause the difficulties, but it has worsened the situation. Covid-19 is not just a health crisis, but one what extends into the economy and society. It will need to be addressed further as the economic costs of this global crisis set in.

Over the past two and a half weeks, Malaysians have stepped up. Hundreds of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have ramped up their efforts to extend basic necessities, thousands from community and religious groups have come together to donate time, resources and money to others, and millions have turned their attention away from themselves to others. Malaysiakini has provided links on how individuals can help. Crises bring out the best and the worst – and large numbers of Malaysians have come together for others, reflecting a deep generous spirit that is part of the core of this society.

The decision earlier this week to develop a working relationship between NGOs and the government to extend food and assistance to the poor should be lauded, as compassion won out over the desire to maintain control. The sad reality is that if social conditions are allowed to worsen, this will make any recovery from this crisis even harder. It is important to recognise up-front that the Covid-19 crisis will extend for months, and the scars it leaves may last even longer.

An important part of this effort is better understanding who the individuals are on the ‘other’ frontline of the crisis - the poor. This allows for thinking through initiatives that can build a sustainable approach to manage the social effects of the crisis which will continue long after any MCO is lifted, and to encourage that resources are spent to go beyond immediate relief to address underlying problems. Beyond the personal stories, this piece brings together available numbers/estimates of the scope of the problem. It closes by laying out a few policy suggestions. Special attention is given to conditions in the Klang Valley.

Assessing numbers - Re-evaluating the poverty line

The debate on poverty in Malaysia is highly contentious as it touches on sensitive issues of race and assessments of governance. Malaysia has been criticised for not following international best practices in measuring poverty and this lack of credibility has stymied effective policy approaches to address core social problems shaping poverty. In recent years, the debate has centred on three areas – the measurement of the poverty line, who to include in assessments of vulnerability (Malaysians or residents) and the policy approaches. From the release of the Unicef study in 2018 to the UN special rapporteur Philip Alston's (photo below) statement last August, this issue has garnered greater attention.

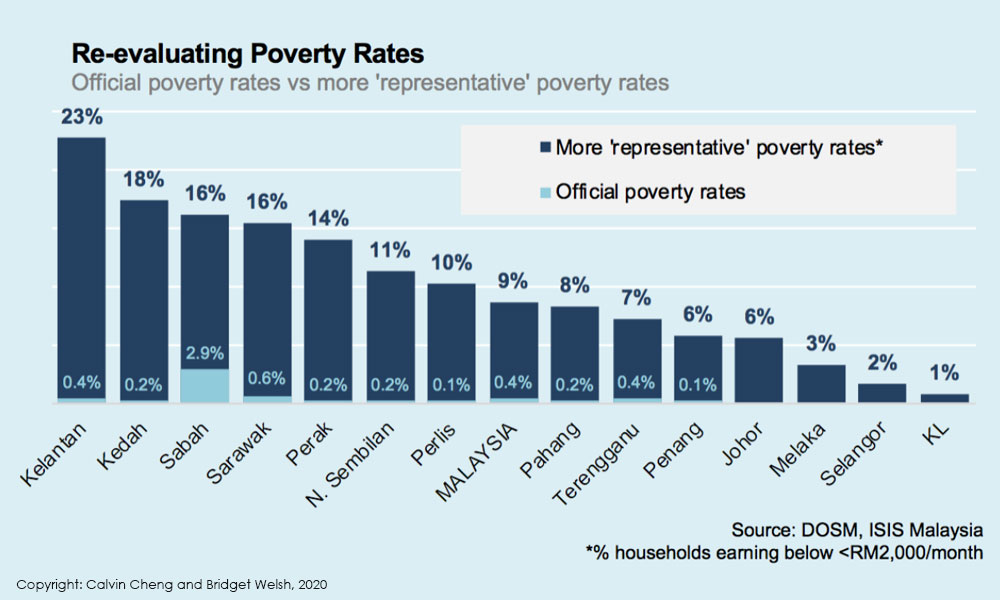

Drawing from our expertise, interviews conducted over the last week and publicly available statistics, we take a look at poverty across Malaysia. Based on official poverty lines from the Department of Statistics, Malaysia has virtually eliminated poverty.

Official national poverty rates have been hovering close to 0.4 percent as long ago as 2016. Experts have argued that this extremely low figure obscures the plight of many poor families. They hold that the official poverty line of RM920 per household is not realistic in light of actual costs. If one considers that the average household size is 4.1 individuals, we are looking one person living on RM224 a month. Even with this low figure, there are an estimated 27,800 households (about 113,900 persons) living in poverty.

This number is just not credible. Malaysia’s poverty lines should be at least double that, with absolute poverty lines closer to RM2,000 per household per month. Using this more representative measure for the poverty line and government statistics, this brings the ‘poverty’ rate up to about 8.8 percent of the country. That is, over 608,000 households (nearly 2.5 million people) in Malaysia are living below RM2,000 a month. The largest share of poverty of citizens, as shown below, is in Kelantan, Kedah and Sabah.

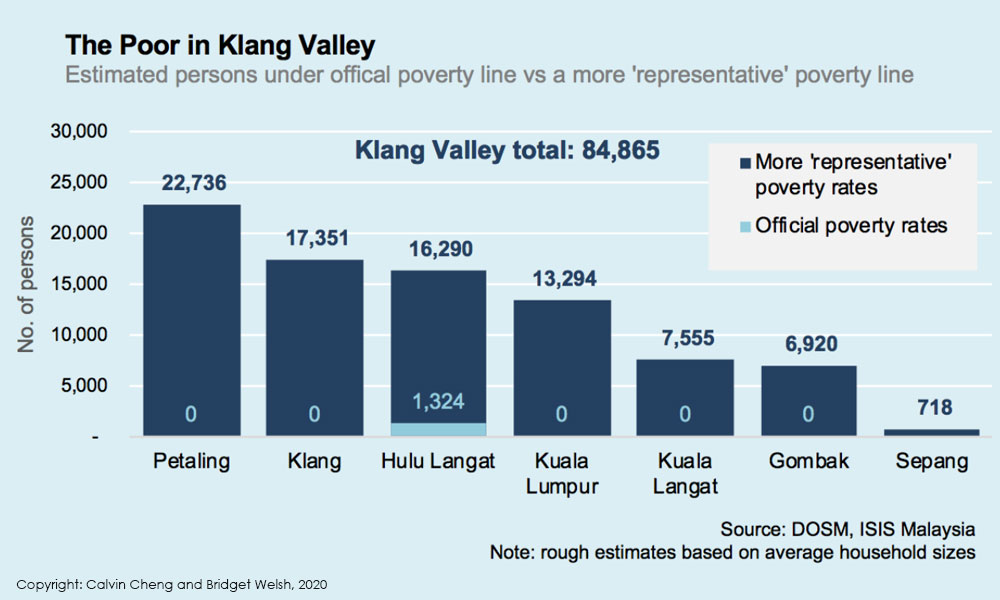

In the Klang Valley, where median incomes and living costs are among the highest in the country, the number of households living under RM2,000 a month is 19,828 households - or about an estimated 85,000 people. The poor are concentrated in Kuala Langat, Klang and Hulu Langat, but stretch across the whole Valley.

Within government, there is a disconnect between what is listed as poor and those who are treated as needing assistance, an acknowledgement of need and vulnerability. Over the past decade, the issue of poverty has been obscured by the introduction of broader cash transfer policies, notably 1Malaysia People’s Aid or BR1M. This has moved the focus away from the official poor to targeting the bottom 40 percent of the household income distribution. The popularity of these cash-based assistance programmes has unfortunately further curtailed already limited discussion of how to address underlying issues of poverty.

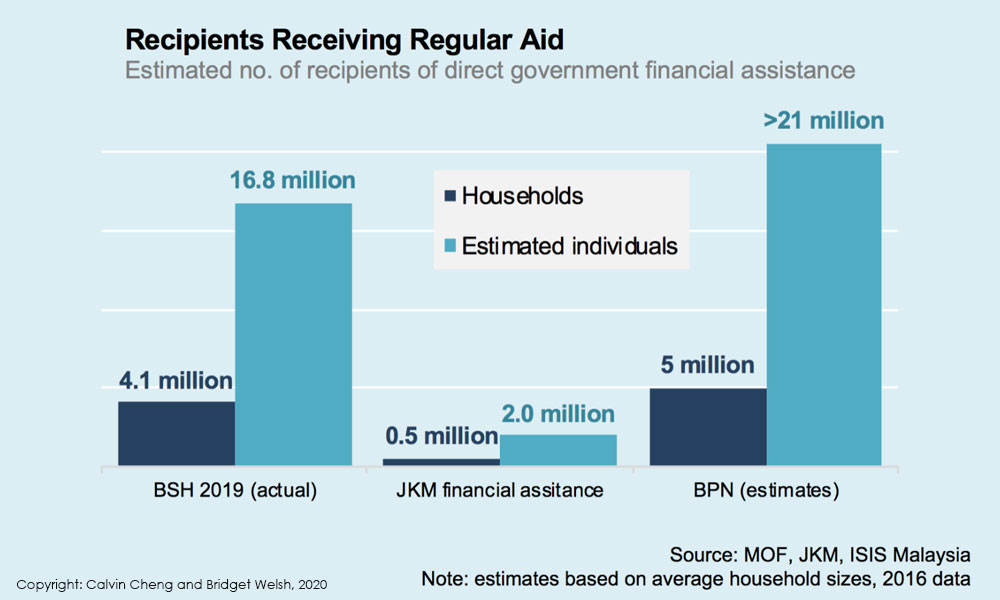

At the same time, these cash assistance measures have highlighted however the scope of vulnerability in society. Statistics from the Department of Social Welfare (JKM) indicate that over 479,000 households (estimated at 2 million people) receive some form of JKM financial assistance, not counting in-kind assistance in the form of food or vouchers. Meanwhile, Bantuan Sara Hidup (BSH) or Costs of Living Assistance (formerly BR1M) recipient statistics suggest some 4.2 million-plus households (an estimated 16.8 million people) received the income-targeted cash transfers in 2019.

Similar programmes exist at the state levels, and the Bantuan Prihatin Nasional (BPN) programme introduced in the stimulus package is based on a similar model but is targeted even more broadly to households in the middle 40 percent of the income distribution. We are looking at an estimated 16.8 million people registered in the system through BSH, more than half of the population. Including BPN households, that figure may be closer to more than 21 million recipients. This number excludes others who might be at risk as their circumstances become affected by a sharp contraction in economic growth, which Bank Negara yesterday projected to contract by -2.0 percent in 2020.

Moving forward, we suggest there needs to be a distinction between relief measures which cover a broader group of people and initiatives for those who are in dire need and whose circumstances will not be changed without other policy approaches adopted to address underlying issues. Even those deemed vulnerable may require a broader set of measures. A key place to begin is to widen the lens of who is being affected by the crisis and reassess who are actually poor and others who are vulnerable but may require another set of measures.

Thinking holistically – Fostering inclusion in understanding poverty

Many of the poor, captured in the stories above, are not part of those registered to get relief. Some of these are delivery problems, people outside the system or who have not registered. The 2018 Unicef study found that around a third of those qualified for assistance did not register, but this varied by income level. Many are unregistered due to where they live, the work they do in the informal sector, and the limited engagement with administrative departments.

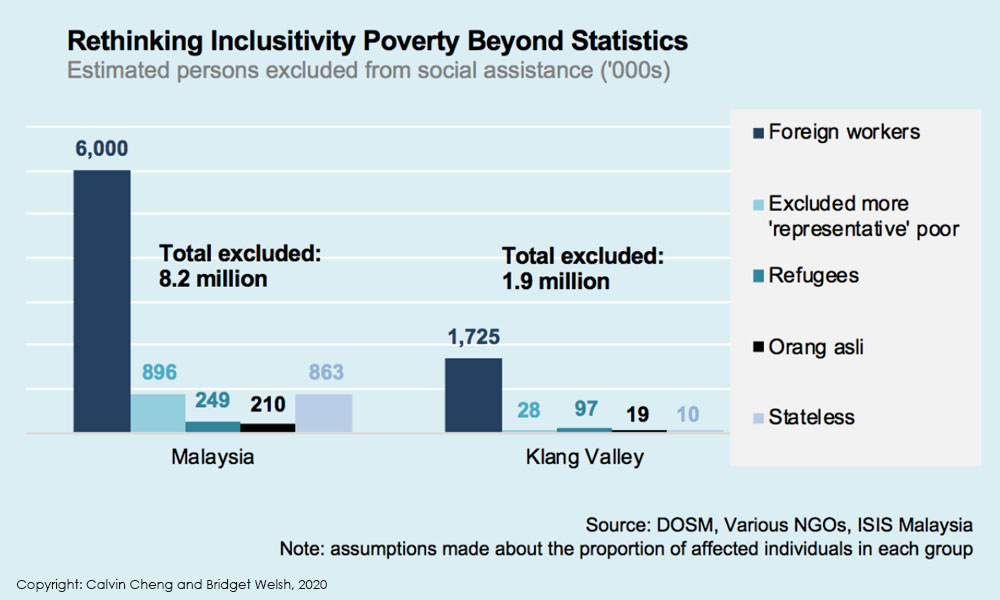

The further challenge is that many who are poor in Malaysia are not included because they lack documents or are left out for a variety of reasons – from citizenship issues to more entrenched exclusion. This includes certain indigenous communities, such as the Orang Asli, migrants, stateless or refugees.

The Orang Asli communities are largely left out of government assistance given to other citizens. They come under a special government department but are also affected by documentation and access issues. Data suggests that there are 198,000 Orang Asli in Peninsular Malaysia, with an additional 126 villages not registered, conservatively estimated to be another 30,000 people. Studies have shown that 92 percent of these communities would be considered poor. In the Klang Valley, there are 74 villages with around a little less than 20,000 people – concentrated in Kuala Langat and Hulu Selangor.

Assessments of migrant workers have long been contested. The Home Ministry estimated 2.1 million documented migrant workers in Malaysia in 2015. An ISEAS report put that figure higher with a total of 3.85 to 5.3 million migrants in 2018, including undocumented illegal workers. NGO estimates put this number even higher, almost 8 million, with an estimated 2.3 million in the Klang Valley. The changing legal status of workers, requiring permits, has further complicated measurements. The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that foreign workers comprise a third of Malaysia’s workforce. As foreigners, they are the largest group in terms of numbers of excluded population not included in the poverty assessments within Malaysia.

Approaches to address migration have been largely law-and-order oriented. The current crisis calls for a reassessment of how to engage this community. Given the health crisis, sending the migrant communities home puts them and regional neighbours at further risk. The reality is that foreign workers play a vital role in the economy and will do so in any economic recovery.

Closely linked are the stateless communities. There are two groups, those born in Malaysia without documentation and those coming from neighbouring countries, many of whom have been in the country for years. The largest share of stateless is concentrated in Sabah, which official numbers list at around 510,000 with NGO estimates reaching 1.9 million.

The number of stateless elsewhere is also debated, and includes Indians born in Malaysia who have not received citizenship and other individuals from abroad not seeking asylum but lacking any documentation whatsoever. Figures here range from 40,000 to 300,000. Based on interviews, we use the conservative estimate of 1.15 million stateless people, with 10,000 of those estimated to be in the Klang Valley. Stateless communities have often lived for years in Malaysia and have no meaningful access to government services.

In terms of refugees, there are an estimated 178,990 formerly recognised, of which 130,000 are of working age in Malaysia. There are others who have yet to register as asylum seekers but fall under the refugee panel, estimated another 70,000 not registered. Disproportionately most of these refugees are Rohingya and other Myanmar minority groups, but many are from the Middle East as well. Over half – estimated 97,000 – are concentrated in the Klang Valley.

If we take what we know about these groups of people, it allows us to see who is being hit by the crisis in a broader way. We estimate that those being excluded from social assistance and among the hardest hit is about 8.2 million, over three times of those who fall within the more representative poverty line of above RM2,000. In the Klang Valley, this is estimated to be 1.9 million people alone.

Rethinking outreach to the poor

These numbers highlight the need to rethink approaches toward the poor. While government assistance is widening and rightly focused on citizens, there are large gaps of citizens, long-time communities living in Malaysia being excluded often without documentation and workers and other vulnerable communities who are contributing to the economy being left out altogether.

The invisible need to be considered in measures moving ahead. Ordinary citizens, businesses and NGOs are helping these communities, but these efforts may not be sustainable as the economic costs of Covid-19 set in. The government’s cash assistance can be complemented by better targeting of assistance and other supporting policies.

Over the past few weeks, there have been important steps taken that reflect the government’s compassionate approach to issues of vulnerability. This approach has been supported across the political divide. Despite meaningful gaps in the needs being met and exclusion of communities, including many in small businesses and the informal sector, initiatives to address the social needs in a more inclusive manner have been introduced, largely based on need.

There are also modest efforts taking place to cooperate and form new partnerships with civil society and businesses in addressing the evolving fallout from the crisis. Even some of the silos within the government in engaging communities are coming down, although this is very much in the early stages.

Moving ahead, a serious rethink of how to address vulnerabilities and the poor is needed, beyond cash transfers of assistance and other immediate relief measures. The poor as a whole need to be recognised and disaggregated, with more attention to how to treat those facing the most serious hardships. A key step is to start getting the numbers right and to stop leaving out the many different groups being affected.

Practically, a task force can be set up to look at different sets of policies that are more holistic in addressing needs and causes along the various dimensions, with greater collaboration with NGOs, academics and international organisations, notably United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). This will allow for better targeting of available limited resources, offer opportunities to find new resources and importantly, allow for the framing of sound policies that will not just ameliorate problems caused by Covid-19, but also work to address the underlying social conditions that will inevitably worsen as the economy contracts.

A crucial part of the way forward is to make the reality of poverty more visible. In closing this piece, we would like to thank the many individuals who shared their expertise and caution readers that the numbers are based on estimates from interviews and available data. There is a need for further research and debate. In writing this piece, the aim is to further discussion and promote understanding, with the hope that as many people as possible can get through this difficult period, that available resources are maximised and that those suffering the hardships described in the personal stories are given a face.

BRIDGET WELSH is a Senior Research Associate at the Hu Feng Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies, a Senior Associate Fellow of The Habibie Centre, and a University Fellow of Charles Darwin University. She currently is an Honorary Research Associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia's Asia Research Institute (Unari) based in Kuala Lumpur.

CALVIN CHENG is an Analyst in the Economics, Trade and Regional Integration programme at the Institute of Strategic and International Studies (ISIS) Malaysia, where his research interests centres around economic development and social assistance. He tweets economics and more at @calvinchengkw and can be reached at calvin.ckw@isis.org.my. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.