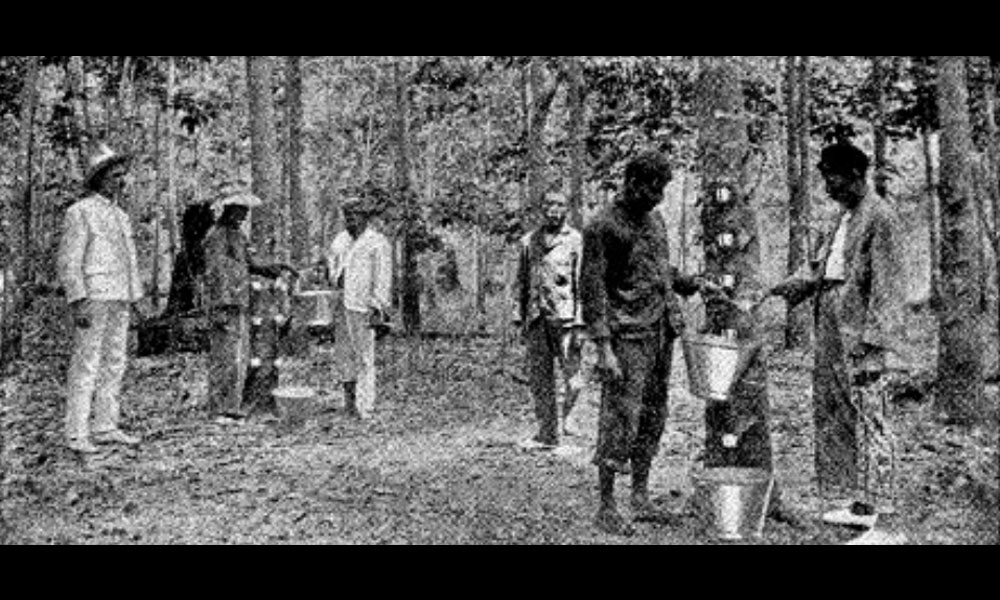

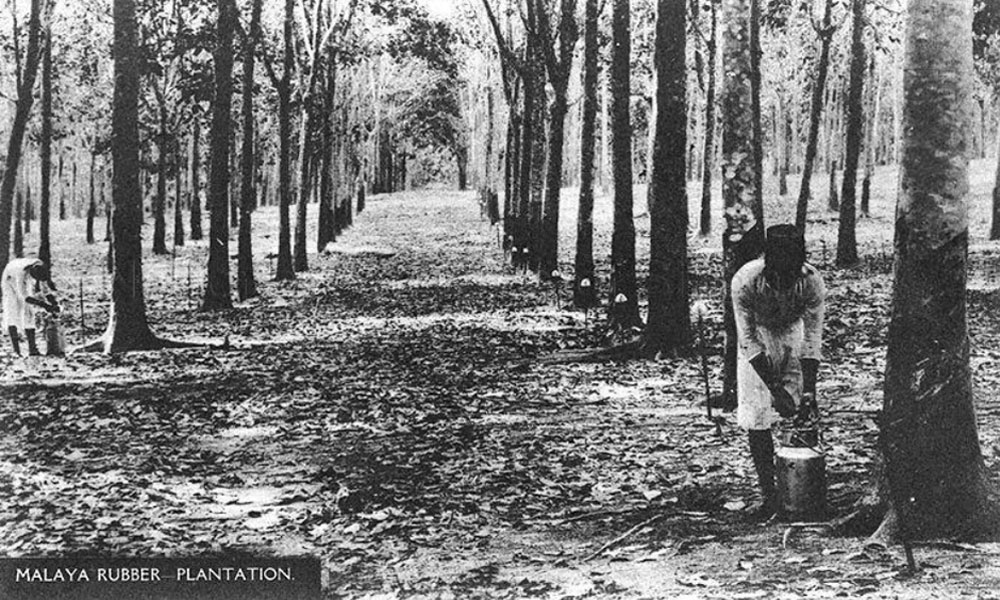

Historian Ranjit Singh Malhi wrote an excellent account of the lives of South Indian workers brought into Malaya to work in plantations, the government sector and others.

The workers were brought in during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The bulk of those who came were Tamils from the present-day Tamil Nadu, but there were sizeable non-Tamils such Telegus and Malayalees from the present states of Andhra Pradesh and Kerala. However, Malayalees found employment in clerical and administrative positions in the colonial government due to their education.

Ranjit rightfully bemoans the fact that despite the great sacrifice in blood, sweat and tears, the contributions of South Indian labour are seldom acknowledged or even addressed in school texts. So much so, the ancestors of the present-day South Indians in Malaysia are largely forgotten to remain 'invisible'.

While Ranjit provides an excellent and sympathetic account of the hardship of South Indian labourers during the colonial period, he misses another side to the same coin. While the South Indian labourers had no choice but to put up with extreme exploitation and hardship, it was not altogether a passive and subservient labour force.

Right from the time they were brought in under the indentured system of recruitment, later replaced by the kangani system, there were numerous acts of resistance against their exploitation and subordination in the country.

Under the kangani system of labour recruitment, the kangani (headman or supervisor) was given the power to recruit from the villages in South India, Although the kangani functioned on the behest of the estate employers, he had great power over the labour from his village. In fact, those recruited were very often his relatives.

'In the direction of India'

The kangani could be troublesome to the estate employers if the latter failed to keep their promises. There have been recorded cases of kangani rebellions in the plantations.

In the period until all forms of immigration were ended in 1938, South Indian labourers sought to resist the manner and nature of exploitation in the plantations and in urban areas. As far as the late 19th century, everyday forms of resistance were there among plantation workers.

In my book on the struggle of plantation labour published in the 1990s, I have recorded numerous instances of resistance amongst the plantation labour. In one particular plantation, Escot Estate, Tanjung Malim, labourers downed their tools and walked out of the estate.

When they were stopped and asked as to where they were heading, they said that they were walking in the direction of India. When they were advised that it was not possible, they said it was alright as they would walk into the sea to be drowned.

According to labour department reports, it was the high rate of mortality among their loved ones that forced them to abandon their employment. The department of labour had recorded many instances of immediate work stoppage in the plantations and urban areas.

Accused of being communists

Since there were no labour unions or organisations representing labour, resistance was often caused by the nature of their workplace employment. Passive and everyday forms of resistance were not organised but spontaneous, the authorities easily put them down. Those engaged in these work stoppages were often deported to India.

Much later, some labour leaders were hung after accusations of being communists. It was in the late 1930s that the formation of Indian organisations saw some form of representation of labour that culminated in the famous Klang strikes of 1941 on the eve of World War Two.

Although the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) was active amongst the Batu Arang coal mine workers, it was not altogether clear that the party had influence among the plantation workers. It has been recorded that in the mid-1930s, the MCP was keen to organise the plantation workers but was unable to do so.

The links between South Indian labour with nationalistic organisations in India, the impact of the cultural movements, the isolated nature of the plantations and others severely restricted the movement of the MCP.

However, during World War Two, the appeal of Indian nationalism, particularly the variant provided by the Indian National Army (INA), saw the political baptism of South Indian labourers. Although the INA failed to liberate India from the British, returning Indians sought to think about their future in Malaya.

This was the time when more and more South Indian labourers became politically conscious and partook in the labour unions that were indirectly influenced by the MCP’s labour fronts.

The period between the surrender of the Japanese and the return of the British was the most active time for labour agitation. Plantation workers joined with urban workers to demand far-reaching changes to improve the lives of the workers. - Mkini

P RAMASAMY, a former university professor, is Perai assemblyperson and Penang deputy chief minister II.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.