Everyone wants to be a TikTok star these days. Nothing surprising about that since, as a phenomenon, the desire for fame re-emerges each time there is a fast-growing social media application that appears to be overtaking more mature ones.

The pivot to video, or more specifically short-form videos, too, is not as new as it is made out to be. In 2016, Facebook CEO (now Meta’s) Mark Zuckerberg announced that the company was pursuing a “video-first” strategy through all of its platforms.

He believed that within five years, most people would mostly consume videos online. Despite the ensuing controversy, he’s not wrong.

Whichever the platform or application (and yes, that includes WhatsApp), “going viral” is a goal for any content creator. It doesn’t matter if you’re a small business entrepreneur, a singer-songwriter, or even a stand-up comic, a preacher, or an aspiring politician (they are not the same).

If you’re serious about making content on social media, you would want as many people to watch what you’ve produced and pray very hard that the algorithms smile upon you on a daily basis.

After all, content is hard work. It is planning, shooting, editing, writing, and interacting consistently to appear effortlessly unrehearsed, relatable, entertaining, educational, inspirational – pick your poison.

Do it well, and in the right way, you may potentially reach thousands, perhaps even millions of people, who will like, share, and maybe follow you. Those numbers are important if one is to establish one’s self as a social media influencer.

Those numbers don’t necessarily translate, however. Ask musicians and bands whose music is in heavy rotation among local music fans through streaming sites and YouTube. They hardly make any money off the hundreds of thousands of listens, and very few people actually turn up and pay for gig tickets.

Politics and social media

The same scenario applies in politics. Many “frequently shared”-tagged videos on WhatsApp and a semi-permanent fixture on the TikTok FYP (“For You Page”), today’s front page of the internet, is still not enough to convince the audience to turn up in support of something.

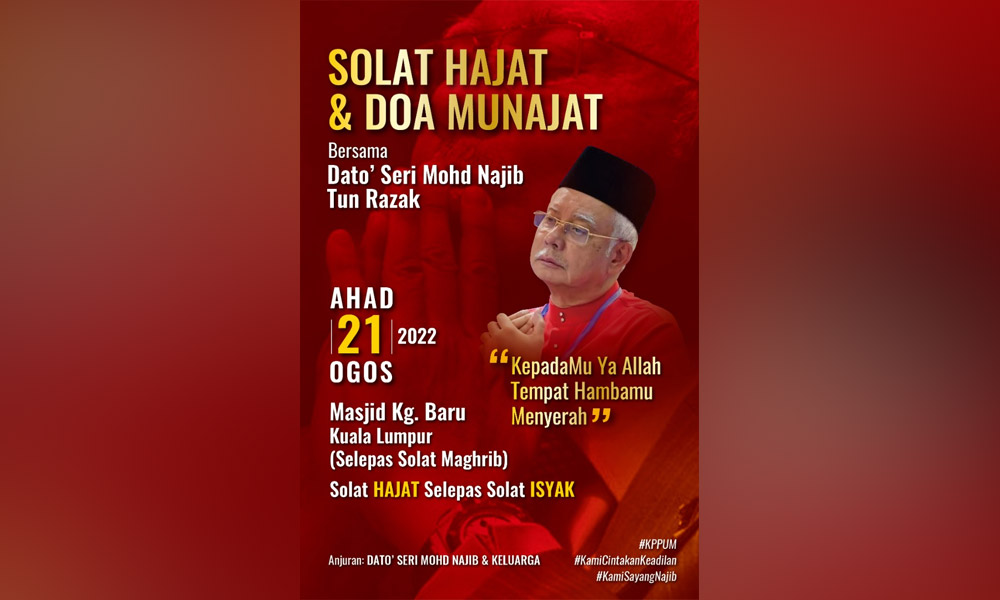

Former prime minister Najib Abdul Razak’s solat hajat on Sunday is just the most recent example of how having millions of ‘followers’ and fans cannot be easily depended on. Despite widespread publicity of the event and over 70,000 likes on his last Facebook posts (not to mention the 4.6 million followers), only a handful turned up at the mosque.

If we were to look back slightly further, we would also be able to recall how widely shared Warisan’s videos were during the Sabah election, in the state as well as in the Peninsular, but it did not translate into winning majorities when polling day came.

Social media and digital campaigns are now permanent features in politics and our democracy, but they cannot be seen as the be-all and end-all of engagement with people. Much like ceramahs and roadshows, they bring the razzle-dazzle, but they are the visible tip of the iceberg of democratic engagement.

Much more work lies beneath it, which is unsexy and, for the most part, boring and thankless.

These include activities like organising local chapters to speak up and respond to neighbourhood concerns; being available to connect family and friends and members of the local community to help and provide services to help solve their issues; and if one’s organisation has the means, to offer or build solutions to those issues like after-school tuition in low-income neighbourhoods, fruit and vegetable baskets in food deserts, teach-ins on workers’ and tenants’ rights, or local micro-mobility in underserved areas.

‘Ground game’

To use Americanism, this is the “ground game” of democracy that allows officials and organisations to leap off screens and into peoples’ homes and lives. Often subsumed under the non-descript sounding “jentera” (machinery) of established organisations, it breeds a comfortable familiarity and accumulates valuable information about the perceptions, needs, and desires of a local community.

Online analytics from online interactions can give a picture of that too, but it won’t be able to fully replicate the emotional connection that comes from meeting people and making a direct impact in their lives.

There will always be room for social media and the media in general to hype intended scandals and run attack meme campaigns, but realistically only the most prominent and already popular will be able to keep up a certain level of virality consistently.

Unlike the days of traditional media, space isn’t a premium on the internet, but attention is. Each wannabe Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez (AOC) will have to compete for attention with the real AOC herself, without the name recognition or access to resources. It’s worth noting that even AOC began as a community organiser in the Bronx.

By building strong local bonds and dependability, social media fame becomes a feeder route for people to lend their physical and monetary support and not just offer emojis of appreciation. - Mkini

LUTFI HAKIM ARIFF is co-founder and podcaster at Waroeng Baru, a not-for-profit collective to promote democratic participation and resilience. He is also the co-author of the book "Parliament, Unexpected" and an unrepentant believer in the power of local independent media. Lutfi tweets at @ltf_ha.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.