Imagine this. A middle-class parent is deciding where to enrol their child for primary school. Should they go private, international, vernacular or public?

Private or international seems beyond reach. The annual fees average about RM30,000, excluding other expenses. (For context, undergraduate studies in a public university cost about RM3,000 a year).

Vernacular schools, whether independent or government-aided (SJKC and SJKT), are not ideal either. Learning in a racial and linguistic bubble seems counter-intuitive to educating a child for life.

The only option? Public schools. Not just any public school. But one where the teachers are demonstrably dedicated, teachers who care for their pupils’ social and cognitive development.

I had such teachers. There were Miss Lim (music) and Mr Rozelles (sports) in the primary. Miss Joan (English Literature) and Mr Simon (Geography) in secondary. Their lessons often led my childish thoughts to different places.

I was lucky to have the right teachers at the right public school, St Xavier’s Institution, in Penang. A much different era it was in the 1960s.

Today, B40 and M40 parents are caught in a fix. Depending on where they live, places in “high-performance” public schools or within the "cluster school of excellence" are limited, and highly competitive.

Many are left searching the public system, which reportedly is running short of qualified teachers in Science, Mathematics and English. Hence, children are burdened with after-school private tuition that costs about RM40 an hour.

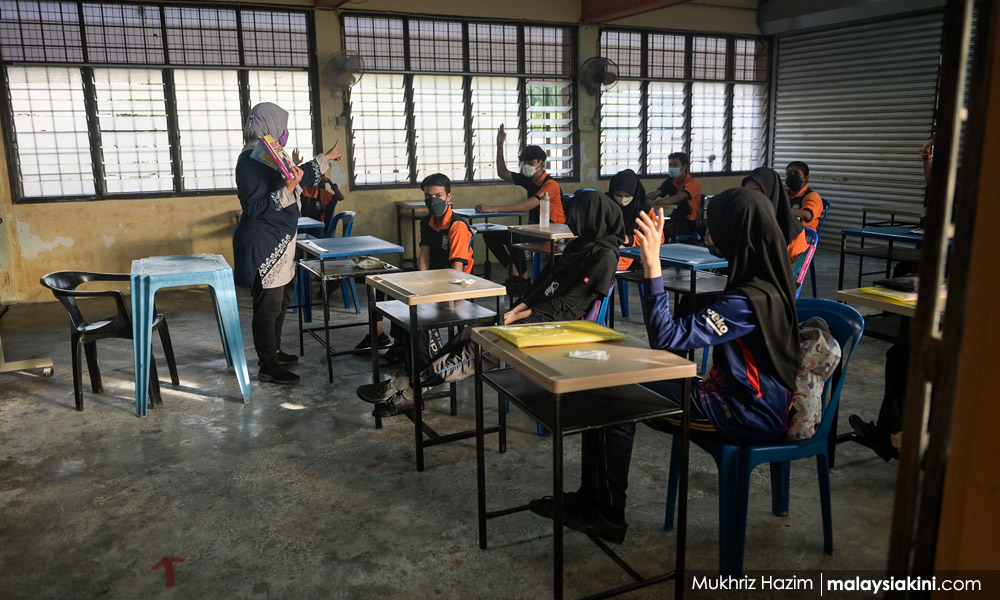

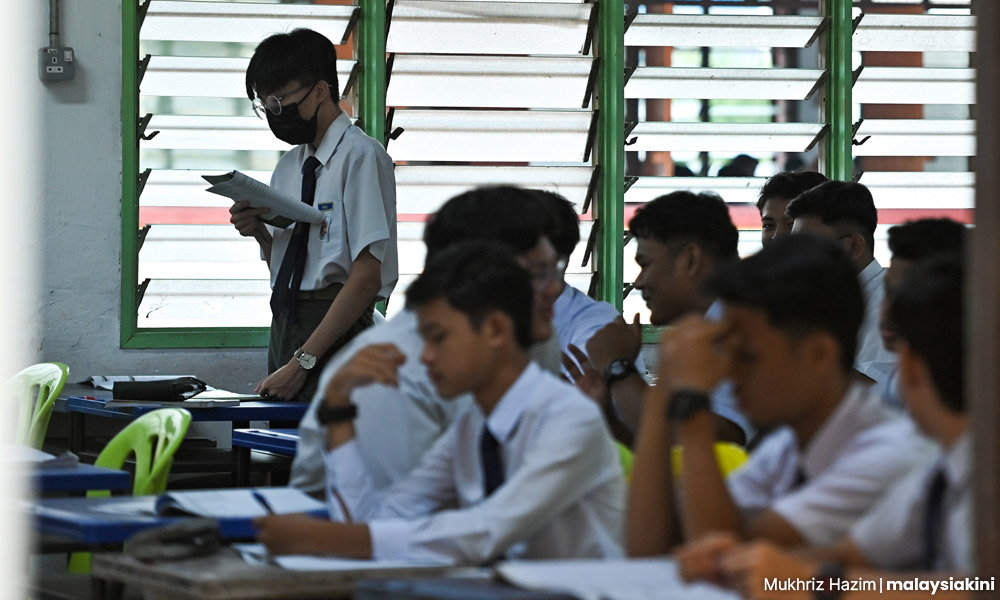

Meanwhile, poor public perception of public schools persists. And, it doesn’t help with scattered reports of declining standards of teaching, lack of teaching resources, low teacher morale, unfavourable post-Covid-19 teaching environment, and infiltration of religion and racial politics in schools.

This brings me to the 48-page executive summary of the Malaysian Education Blueprint 2013-2025 (prepared by McKinsey & Co at a cost of RM20 million).

The glossy report outlines the paradigm shifts that are needed to transform the education system. An Education Performance and Delivery Unit (PADU) was set up under the Education Ministry to carry out the recommendations.

With two more years to go, PADU’s report card is less than rosy, particularly in Malaysia’s rankings in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA).

(Some have questioned why an American consultant was commissioned to assess our education system when the US hovers around 20-something in its PISA rankings compared to China, South Korea, Japan or Singapore - where they are consistently placed in the top 10).

Parents’ expectations

Few parents, however, would care less for the country’s PISA rankings or read the blueprint in detail. Top in a parent’s mind are these factors: the school’s location, its reputation, class sizes, demographics of its teachers and students, the curriculum and extra-curricular activities.

Where would parents find such information? Certainly not from the blueprint. They would likely Google for the school’s rankings, if any, defer to other parents’ experience with certain schools, or rely on their perception of what makes for a “high-performing school”.

It’s common knowledge that the world’s high-performing school systems – for instance in Singapore and South Korea - are those that have the right people in the teaching profession with a clear career path to becoming effective instructors for children in their formative years.

This means selecting the brightest school leavers for teacher training and making it as competitive as applying to degree programmes in medicine, the sciences, engineering, or law.

What matters most in a school leaver’s mind? The earning potential, perceived prestige and career path in what they choose to study in university. Teaching, however, is less likely to be on the list of first preferences.

According to 2021 figures, early-stage salaries range from RM1,700 (DG29 for non-graduate teachers) to RM2,200 (DG41 for graduate teachers).

And it takes about 25 years for a teacher to reach the administrator’s scale of DG54 or about RM12,000.

Teachers’ salaries are linked to pay rises in the public service. The last pay rise was in 2019 of between RM 70 and RM 230 per month, depending on the grade and length of service.

News that further undermines a public school teacher’s dedication to the profession is this - another increment is unlikely in the short-term, according to the prime minister, given the national debt of RM1.5 trillion.

Teachers’ salaries rarely reflect the importance of their work. However, higher pay does not guarantee better teachers.

Intrinsic motivation and passion for teaching, school culture and supportive leadership – these values must be present in the workplace.

Without this, public school teachers will remain overlooked and unrecognised as the critical nurturer of young minds.

The ultimate losers? Children whose parents cannot afford to fork out RM30,000 a year for their early education. - Mkini

ERIC LOO is a former journalist and educator in Australia, and a journalism trainer in parts of Asia.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.