We at the Centre for the Study of Communications and Culture (CSCC) write to express our concern at the recent `revelations’ by Gobind Singh Deo in his capacity as the minister for communications and multimedia.

We have no objection to his wanting to get rid of the odious, the repugnant Anti-Fake News Act (2018), a law that has no place in a democracy.

Equally, we would welcome any serious attempts on his part to critically study, amend, even repeal, other laws, such as the Printing Presses and Publications Act (1984/87) and the Communications and Multimedia Act.

But we wish to assert that legalistic measures alone are not sufficient to reform institutions that have long existed without a coherent vision for the rakyat (and, as we shall argue, by the rakyat), despite being funded primarily by Malaysian taxpayers.

While liberating legal frameworks are important, we all need to understand that the media – in this case, public media – produce unique products. They are economic products, like canned sardines, to be sold to the public.

Yet, media products - news, current affairs programmes, fictional TV like soap operas, films, documentaries – are also cultural products. They contain meanings, ideas, ideologies and are pivotal in defining social consciousness in this digital world.

Just look at the tugging-at-the-heartstrings photographs and videos of Dr Mahathir Mohamad during the GE14 campaign period, leading up to his pre-GE14 Facebook appeal to the nation.

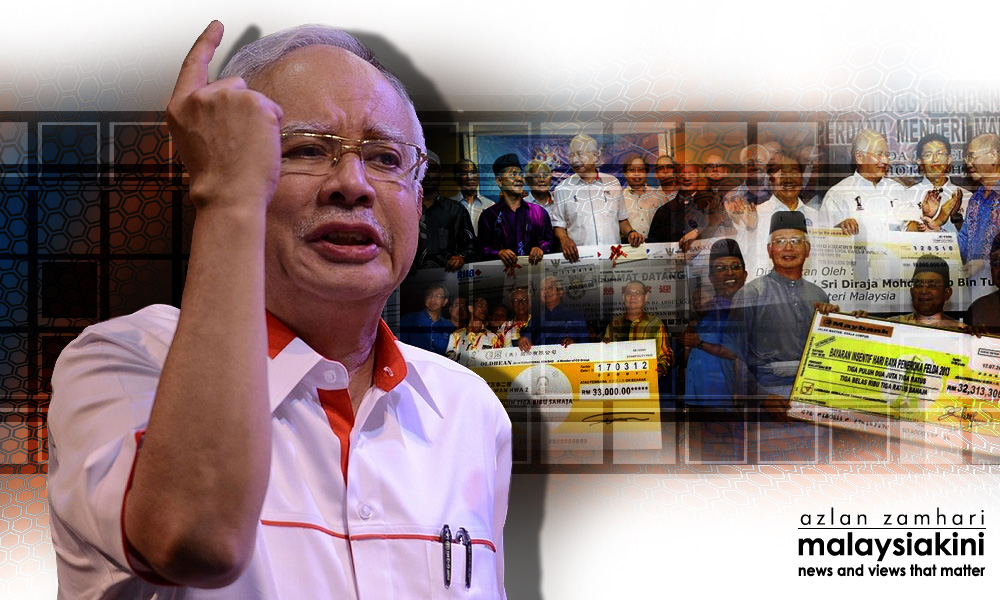

Then compare them with Najib Abdul Razak’s propaganda, characterised by his last speech virtually telling Malaysians that he could easily buy our votes and that 'cash is king' - and we will see the significance of media in providing us with cues, imagery and meanings.

In a closed society where we derive our meanings, our ideas, from a restricted number of sources, the media – old, new, mainstream, alternative, social – thus plays a key role. Malaysia has long been that closed society.

Public service is not government service

Opening the media, making the media answerable to and in service of the people requires a view beyond a legalistic framework, to understand this cultural nature of the media and grasp what “public service” entails.

Public service is not government service. Since its inception in 1963, RTM has been nothing more than a government propaganda arm. This has to stop. It does not – and cannot – stop by becoming a corporate entity, as Gobind strongly suggests it should.

It stops – and takes on the role of public service media – by educating itself and its personnel about what being a public service entails. Indeed, in this regard, Gobind should avail himself of the many studies and policy papers available outlining successful public service undertakings.

He must not act like a populist politician, giving the (undifferentiated) masses what he thinks they want. Like the World Cup. Yes, in the short term, this will make him and RTM popular.

But competing in the popularity stakes with commercial TV and Astro is not the way to go. Malaysians deserve more than just media that is essentially commercial pap, media that is much of a muchness.

Original, creative material

We need genuine variety, not more pale copies of Korean soap operas or whatever the latest entertainment craze is. And coming up with that variety, that originality, is the role of public service broadcasting; a role RTM can and must play if it is largely going to be funded by taxpayers’ money.

Developing a public service ethos or culture within RTM thus should be the top of the minister’s concern. Reform of RTM needs to go beyond the attractiveness of the programming/content. The institution receives state funding but has always served government interest, rather than public interest.

There is a significant difference between state and public service media; state media has no place in a democratic society. Hence, a thorough review of RTM's structure, governance and funding sources must be done.

Public service broadcasting requires independence and autonomy from the state and other bodies. It requires public funding with no strings attached.

Hence, governance would be in the hands of, say, a board of governors made up of upstanding citizens and professionals not representing any political party.

What it should not be is a board of pensioners from the civil service – like the fossilised Film Censorship Board – who would not recognise art and creativity if they tripped over them.

What is important for public service media is to ensure governing bodies that are professionally selected, possibly by parliamentary committees or, even better, by the industry players and civil society.

Next, RTM’s brief would be to come up with original, creative, challenging material that may even question the norm. To begin with, a revived and reconstituted RTM should start to think of developing documentaries that address the concerns of all our societies.

Documentaries and even current affairs programmes may be guided by, say, the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs); goals that cover everything from the environment to human rights.

A reconstituted, public service RTM must also understand and appreciate the multicultural, multi-religious and multi-ethnic nature of Malaysian society. And celebrate that, rather than privileging some against others. Minority groups must be recognised and not marginalised.

It will take time, certainly, and, of course, it will require political will.

But the changes need to start now, guided by the principles of serving the people and not simply to make money. The old days of “cash is king” must be replaced by the following years of “the people are sovereign”.

ROM NAIN and GAYATHRY VENKITESWARAN represent the Centre for the Study of Communications and Culture, the University of Nottingham, Malaysia Campus. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.