QUESTION TIME | More than two months after GE14, why is it important to ask this question?

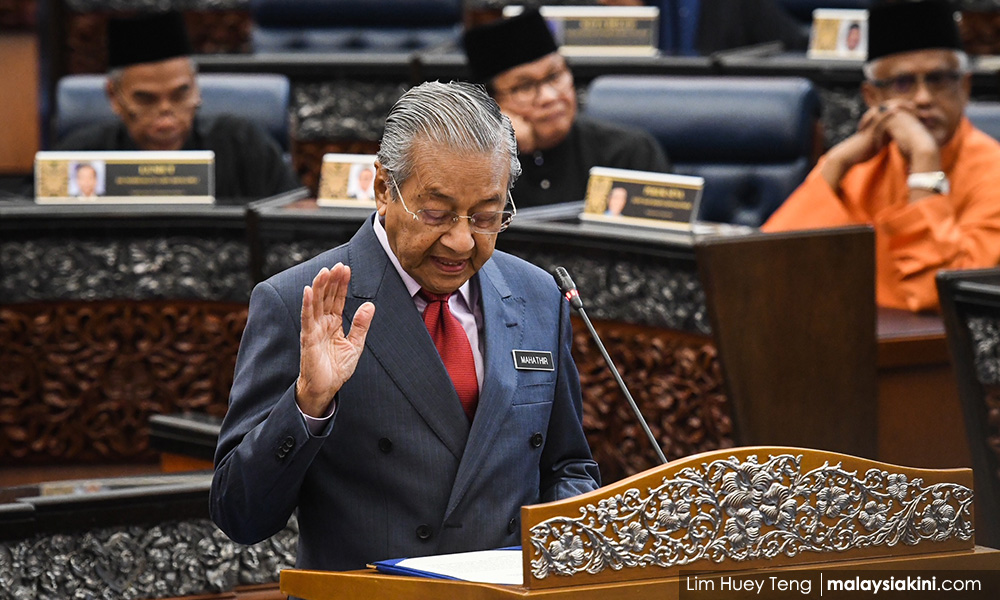

That’s because many still attribute Pakatan Harapan’s victory to Dr Mahathir Mohamad and give that reason over and over again for why he should be given a free hand to run the country and to pick and choose the cabinet as he pleases, even to the point of disregarding consultation or seeking consensus whenever possible within Harapan.

This is a vexing, contentious question and to blithely concede that he won the May 9 election for Harapan is to ignore the history of the reform movement (“reformasi”) which started two decades ago, the performance of past elections and the involvement of many who fought BN over a very long period of time.

It also ignores the statistics of the latest general election, which indicate clearly that Mahathir, who was brought in to bring in Malay votes for Harapan, did very little of that despite his fairytale-like reappearance as the new interim leader of Harapan to get rid of a common enemy, Najib Abdul Razak.

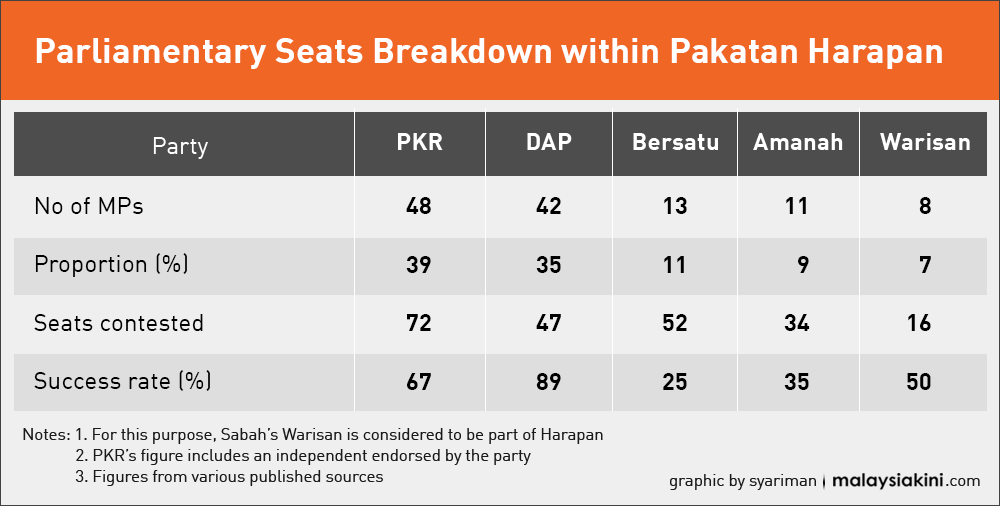

Let’s start first with the election results for GE14. As pointed out in the first article in this series, Mahathir’s Bersatu performed the worst among Harapan parties, with an abysmally poor win rate of 25 percent (see table below). The argument used to explain this is that Bersatu faced tougher seats. That is not necessarily true as we shall see later. Even in Mahathir’s home state of Kedah, Bersatu’s performance was rather lacklustre.

Bersatu contested only in Peninsular Malaysia and among Harapan coalition partners, contested the most seats with 52, followed by PKR with 51, DAP with 39 and Amanah with 27. PKR won over 80 percent of the seats it contested in the peninsula but 67 percent overall. DAP won 89 percent of the seats it contested.

There is a clear indication from these figures that Bersatu’s performance was poor. The key question is whether Mahathir’s Bersatu played a major role in swinging the Malay vote. If it did, then there should have been a significant swing in Malay votes in the Malay heartland, generally considered to be Kedah, Perlis, Kelantan and Terengganu, with more seats being won here.

Let’s look at the breakdown and results for parliamentary seats contested in these states to see if that’s true.

In Mahathir’s home state of Kedah, Bersatu contested six seats and won only three for a 50 percent win rate. Amanah had a win rate of 33.3 percent, winning one seat. But PKR had a 100 percent win rate for the six seats it contested. The three parliamentary seats that Bersatu won were Mahathir's in Langkawi, Mukhriz's (photo) at Jerlun and Amiruddin Hamzah's at Mahathir’s old seat of Kubang Pasu.

This is a clear indication again that Bersatu made little headway in terms of swinging the Malay vote. In both Kelantan and Terengganu, Harapan was whitewashed, the swing of Malay votes away from Umno going largely to PAS.

In terms of parliamentary numbers, Bersatu hardly made any contribution in terms of swinging Malay votes. But was is it different for the state seats? Let’s see.

Taking Kedah first, Bersatu obtained just five state seats from 14 contested for a win rate of 35.7 percent while Amanah got just three seats from nine contested for a slightly lower win rate of 33.3 percent. PKR, however, did outstandingly well, winning eight seats out of 11 for a 72.7 percent win rate while DAP won both the two urban seats it contested.

Again, a swing in the Malay vote from Umno went largely to PAS, which won 15 state seats compared with Harapan’s 18 and Umno’s three. With only five seats against PKR’s eight, Mahathir’s son Mukhriz became Kedah menteri besar.

As with the parliamentary seats, Harapan lost all state seats it contested in Kelantan and Terengganu, with the Malay swing going from Umno to PAS, though PKR won three out of five seats in Perlis for a win rate of 60 percent.

Mahathir new to 'reformasi'

The ultimate conclusion from all this is that Bersatu failed to deliver a significant swing of Malay votes in the Malay heartland states and that PKR would have most likely been able to hold its own there, without Bersatu. Also, while there was a swing away from Umno, it went to PAS instead of Bersatu.

The rest of the Harapan parties did better, indicating that even if they had decided to go it alone, they could have won the election. Mahathir did not necessarily win the election for Harapan, even though this seems to be what many people are thinking.

And what about the other states that Harapan won in the peninsula? Let’s take the three most important (see table below) and look at how the state seats there went. The story is the same, except for Johor where former deputy prime minister Muhyiddin Yassin’s presence may have made things slightly different, with Bersatu performing significantly better than PKR.

Otherwise, PKR and Amanah performed much better than Bersatu. Despite holding a lesser number of state seats, Bersatu candidates became menteri besar in three states - Perak, Kedah and Johor. In Perak, the sole Bersatu representative became menteri besar.

The inescapable conclusion from all this is that Bersatu not only obtained representation and power at all levels far in excess of its representation but also that its leader Mahathir has most probably been credited with far more than what he is entitled to in terms of the Harapan victory. Very possibly Harapan, without Bersatu, would most likely still have won the elections.

Going back in time, calls for the “reformasi” that began two decades ago, in 1998, and in fact against Mahathir’s rather dictatorial rule when he ousted Anwar Ibrahim as his deputy. In 2008, when PKR and its partners won five states in Peninsular Malaysia, Mahathir was a staunch Umno supporter.

In 2013, when Pakatan Rakyat took 52 percent of the popular vote, Mahathir was still part of Umno. The change was already happening in the political landscape without Mahathir - people did not want corruption, they did not want a dictatorship.

As we all know, reformasi started with Anwar and expanded as others joined in the struggle to work for it, including long-time opposition stalwarts like Karpal Singh and Lim Kit Siang. Anwar spent 11 years in jail for it, the person who most suffered for it, who refused to run away from that even when the opportunity presented itself.

He is more likely to have reformed than the others who jumped on the Harapan bandwagon in the last hours of the long struggle against BN. Some of them live in the comfort of the gains they obtained during the time Mahathir was in power. The road to victory ran for 20 years; Mahathir was on it for just a few months.

Finally, was Mahathir needed to make a smooth transition to power? Even there, his contribution may have been limited. It is fact that he has deep differences with the royalty. Someone like Anwar’s wife, Dr Wan Azizah Wan Ismail (photo), may have been more acceptable to the king, who, according to reports, asked her to form the government. Wan Azizah declined, saying the coalition had picked Mahathir.

This not to say that Mahathir did not help, he did. But his contribution must pale in comparison to the others who gave their life to reformasi and suffered for it. If Mahathir is always true to the spirit of the reformasi that Malaysians voted for, then it all would be worthwhile. But he wavers sometimes.

Now it is incumbent upon Mahathir to keep to his word and the promises he made publicly, instead of changing them at his own whims and fancies - just like how Wan Azizah honoured her promise despite a poor performance by Bersatu in the elections.

Mahathir promised that the cabinet will reflect seats won by the parties but he broke that promise. He promised he will be a transitional prime minister for perhaps two years but he now gives no deadline to step down. He has talked about consultation and consensus, which would be more in keeping with his party’s 13 seats but he does not do this in the appointment of the cabinet and other major decisions he makes.

A new coalition has been elected but he instead uses a council of elders to make vital decisions. Mahathir cannot keep on breaking promises, making questionable decisions and expecting everything to go on as normal. There will be repercussions.

This is the second in a series of articles on Malaysia, post-GE14. The first was titled Mahathir’s patently unfair cabinet. The next article in the series will deal with the issue of whether we need a council of elders.

P GUNASEGARAM says that we must always remember that it is us Malaysians collectively who changed the government and we have expectations of what we want with that change. E-mail: t.p.guna@gmail.com -Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.