Dr Mahathir Mohamad never answers a political question directly. When journalists asked whether he would make a comeback in the next general election, he said maybe – only if the people will it. He told the press that many people still visit him every day, telling him to contribute his experience to the country.

Every time the country dips into a crisis, only one man could “save” her. And it seems that nobody but the man who held the highest office in the country for 24 years could do so.

Like every politician, the answer of “the people’s will” is a convenient escape. When Pakatan Harapan lost power in early March, they called the new government illegitimate because it was formed against the people’s will. When Perikatan Nasional (PN) came into power, they said this was the government of the people’s will.

Every politician wants to claim they hold the key to the masses. Having the people’s will is a sacred validation; misusing the people’s will is a sacrilegious violation.

The “people’s will” gives Mahathir two choices: Fight back or sit back.

Fight back

Always keeping an open mind about rules and principles, Mahathir is a keen proponent of “anything works”. He prefers if you discounted his comeback so he could orchestrate a surprise. A surprise is every tactician’s favourite necessity.

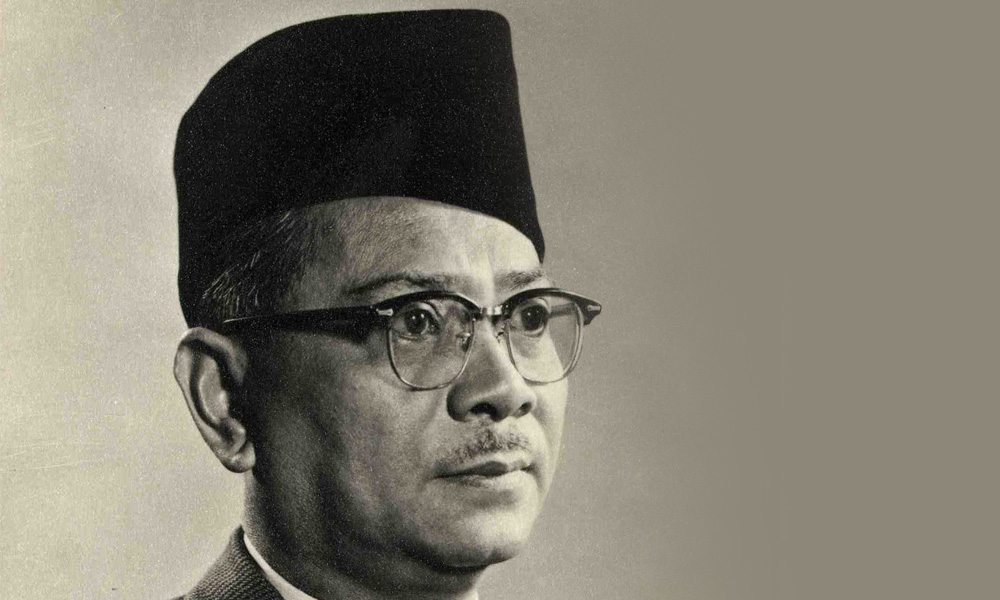

Mahathir’s foray into politics was marred with a sacking. He was thrown out of Umno by Tunku Abdul Rahman’s team, who thought his line of politics was extreme and unpalatable to the taste of Malay-English male and gentry.

During his exile, he wrote a book that cemented his political thinking about race in Malaysia – The Malay Dilemma. When the tide turned in his favour, he rode it with Tunku’s rivals and returned to mainstream politics. The expedition from exile to elitism took a mere four years. That was his first political comeback.

Between then and now, Mahathir was at the epicentre of numerous comebacks. If his party members didn’t like him, he would find a faction to get rid of the rival faction. If his party leader didn’t like him, he would find a way to get rid of the party leader. If the party didn’t like him, he would find a way to get rid of the party altogether.

If Umno didn’t work, there could be Umno Baru. If Umno Baru didn’t work, there could be Bersatu.

A tool to achieve power

To the party members, a political party represents the struggle and the cause. To the highest leaders, a political party is but a tool to achieve power.

History tells us that Mahathir is always capable of a comeback. But history is also ageless and limitless. Mahathir is 95 and left with limited options.

We have gone through this before. In the last election, we thought a 93-year-old man could not take the demands of an election campaign – five to six events a day, long hours of standing, pressures of the public spotlight and an eager crowd.

But he did. In fact, he did what most of our younger bodies could not have done. Pakatan Harapan politicians were so dependent on him that, for a moment, we were made to believe we could not have won without Mahathir.

At that point, we knew that Mahathir was a different species. Age is not a problem for Mahathir – but time is.

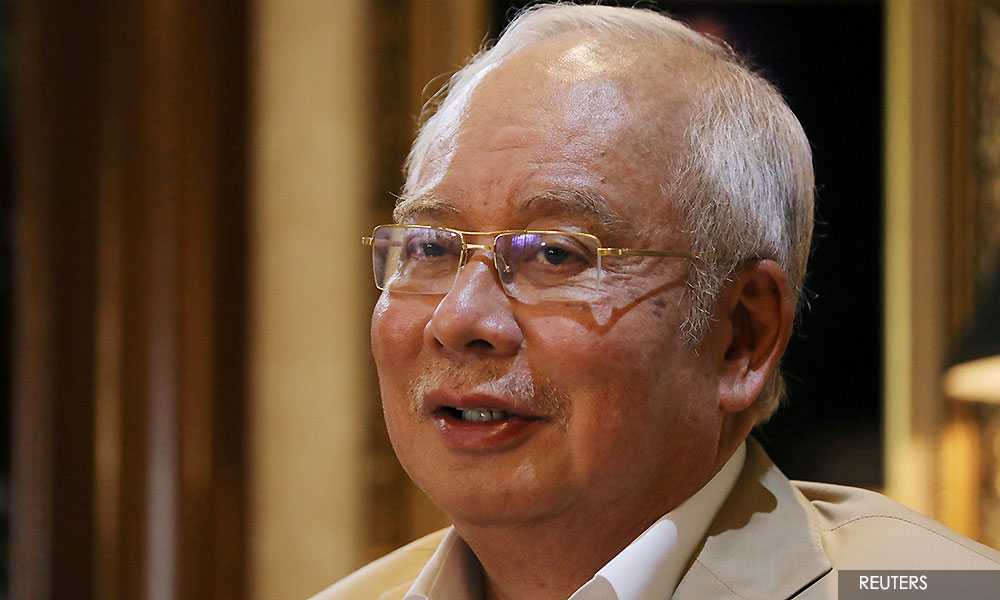

It took Mahathir three to four years to oust Najib Abdul Razak (above) from the highest position, and only two to lose it again. Muhyiddin Yassin’s government may have many cracks within, but they are a collection of experienced warlords who understand the importance of holding power.

Even if Mahathir pushes his bodily limits to make a comeback against Muhyiddin, he would have been 98 by then. The Palace has closed its doors, the politicians of Harapan have developed a newfound mistrust, and the people have come to their senses that the country depends on more personalities than just one grandmaster.

A comeback is forever possible for we are fearful of history, but a comeback is unlikely, given our poverty in age and options.

Sit back

Many people would have designed Mahathir’s legacy differently.

We all say the same thing: If Mahathir had simply won power for the coalition of hope, and handed over power to a younger leader in Anwar, the country would remember him as a heroic saviour. Since we are a country of high filial piety and timeless respect for our elders, we would even go so far as to erase his 22-year misdeeds from our memories. We can be selective and we can be short-term if we want to do others a favour.

But Mahathir didn’t. His two-year tenure as prime minister reminded us more of the less flattering remarks we shared of him during his first term.

He didn’t sit back the first time; it’s not too late to sit back now. And I suspect that he is single-minded in building that final legacy of having his version of events retold so that we could remember him fondly. He has little else to lose.

Mahathir hopes you remember that he was free of fault in the seemingly illegitimate rise of the PN. He said it was Muhyiddin and Anwar’s fault – both were power-crazy without constraint. Muhyiddin's fault was worse, for he “betrayed” Mahathir. A few days later, Mahathir also blamed Najib, who manufactured a country-wide hate campaign against the non-Malays.

Mahathir also hopes you remember that Anwar was not the right person for the top job. When he was prime minister, Mahathir promised that Anwar would be his successor – implying Anwar’s suitability for the role. But when he lost power, Mahathir said Anwar might not have the right “character” for prime ministership – not even the deputy prime ministership. According to Mahathir, Anwar was too “political” than administrative.

Most of all, Mahathir hopes you remember that he is a reluctant leader. His half-a-century long involvement in active politics was out of the people’s wants and needs. He never wanted power for himself; the people wanted it for him. He had always acted out of the sacred reservoir of the “people’s will”.

Now it is empty.

JAMES CHAI is a legal consultant and researcher working for Invoke, among others. You may reach him at jameschai.mpuk@gmail.com. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.