This call to action on prison overcrowding is purely an act of conscience and non-partisan.

Prison inmates have as much right as anyone else to remain safe from diseases. This is all the more so when the disease is as infectious and dangerous as Covid-19. With zero mobility, prisoners become sitting ducks. The situation is very similar to that in care homes. Once the virus gets a foothold in them, the consequences are dire. In fact, there have been such sad cases across the world where the virus had spread within prison walls, and in care homes.

It is therefore wise for us not to sentence violators of the movement control order (MCO) into crowded prisons. We are putting these people at risk, and if they happen to be infected, they will in turn definitely infect other inmates.

The real issue here is that Malaysian prisons are overcrowded. This was an issue that I had discussed with Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin before, in December 2019, when he was home minister.

The prisons are overcrowded very much due to the way we handle drug offences. Up to two-thirds of inmates are linked to drugs one way or the other.

Reportedly, there are currently 73,000 inmates housed in facilities designed to take only 52,000 inmates. If strict social distancing is mandated in these prisons to prevent the spread of Covid-19, the system probably would only be able to house an even smaller number. And this is not a short-term situation that we are dealing with; we do not expect a vaccine against Covid-19 to be developed any time soon.

As the Covid-19 situation grows worse, Indonesia and Turkey, for example, have released tens of thousands of prisoners to reduce overcrowding and to limit its spread. The US is also taking steps to reduce its prison population.

I had opportunities to have very cordial and informative private conversations with prison officers in the states of Selangor, Malacca and Johor on several occasions in 2019.

Most of the prison officers I met agreed that we need to rethink the issue of drug offences. They knew for a fact that prisons often function as a “university” (to use the word of one of the officers) for people who had committed petty crimes, especially drug offences, to pick up new and more sophisticated criminal skills, and to be recruited into larger crime networks.

Given the huge prison population, they found it almost impossible for proper corrective work to be carried out on prisoners. Medical services are also sorely lacking. This was a big worry for the prison officers and guards. There are just too few doctors and medical personnel allocated to the prison service vis-à-vis the actual prison population (not the designed capacity, which is smaller).

Some were very worried about tuberculosis. They have seen some of their own colleagues dying from the disease. It’s a “silent killer”, says one of them.

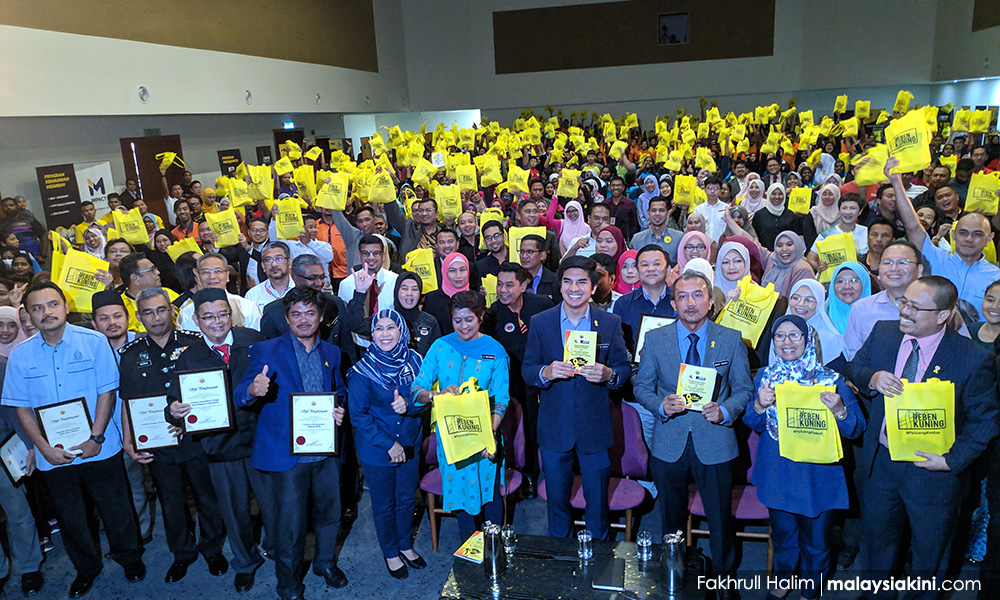

These officers appreciated former youth and sports minister Syed Saddiq Syed Abdul Rahman’s “Yellow Ribbon” campaign that created more than a thousand jobs for young inmates in the Sungai Buloh prison complex, who had short prison terms and were of good behaviour, and got them to stay and work at worksites near Bukit Jalil.

Nurul Izzah Anwar has also since 2018 campaigned for improvements to our prison system, targeting 75 percent of eligible, non-violent criminals to be absorbed into corrective community programmes. In 2018, she even tabled a private member’s bill on prison reform.

During Najib Abdul Razak’s period as prime minister, a Korean professor/consultant Chan Khim was paid handsomely to promote the National Blue Ocean Strategy (NBOS). One of the most “celebrated” measures, which Chan wrote about in his second volume Blue Ocean Shift, was to put prisoners in army camps.

Six Army camps – Camp Mahkota in Kluang (7th Infantry Brigade Headquarters), Camp Syed Sirajuddin in Gemas, Camp Desa Pahlawan in Kota Bharu (8th Infantry Brigade Headquarters), Camp Sultan Abdul Hamid in Alor Setar, Camp Batu 10 in Kuantan, and Camp Paradise in Kota Belud throughout Malaysia all have such installations.

If all the generals I had discussed this with, none were supportive of it. In fact, they hated the idea. I personally visited the one in Kem Mahkota, Kluang, in 2018 in my capacity as deputy defence minister, and I was convinced that it was all a very foolish idea. In essence, it was a sidestepping of a real and present problem.

The fact is that we have too many people sentenced to prison than we have prison spaces. But the core challenge is something else, and the solution is not more prisons. That would cost more continuous expenditure, and would still be an avoidance of the problem.

Looking into the nature of our criminal offences, we find that there is a huge representation of drug offenders. Instead of decriminalising minor drug offences or investing in socio-economic measures to help the younger vulnerable members of society, the problem under Najib was to outsource the problem to the armed forces.

Now, the armed forces are trained to defend the country and to use weapons against external enemies. They are not prison guards. They are not our excess labour force.

As it turned out, the inmates were not keen to work. They had to be forced to work. In the fanciful thinking of Chan and Najib, prisoners would happily mow grass in military camps. Reality does not work this way.

The scheme was finally abolished by the National Security Council, of which Muhyiddin (photo) attended as home minister, in 2019. I was told that there were attempts to move the prison inmates to new privately-run prisons. But again, this is really not the solution.

To cut the size of the prison population in order to allow for social distancing to be implementable, there is an urgent need for an amnesty or Covid-19 special paroles for people found guilty of petty crimes or small drug offences. There is really no time to lose on this matter.

I texted Muhyiddin on Dec 23, 2019 and gave him feedback that prison officials told me about prison health scares and decriminalisation of drug usage.

He told me that the prison authority was working with health authorities on preventing tuberculosis infections in prisons.

On the decriminalisation of drugs, he added that a special committee had been set up including representatives from the Health Ministry, Youth and Sports Ministry, AADK (anti-drugs agency) to discuss various aspects of legislation on drugs.

Interestingly, Muhyiddin told me that the committee had agreed in principle to move in the direction of decriminalisation. However, there were many technical details to be ironed out. For instance, how do you treat a drug addict who during the time of arrest has certain amounts of drugs in his keep? Do you treat him as a criminal and charge him under the Dangerous Drugs Act, or should he be treated like a drug addict because the quantum is small?

He reinforced the need to speed up the whole process, “as nearly 70 percent of those that are in prison now are drug-related.”

Prison overcrowding is an issue that the prime minister is familiar with and he himself had competently and comprehensively understood the matter when he was home minister. It was bureaucratic niceties that stopped him from acting much faster.

I call on the prime minister now to take a personal interest in the matter. In the immediate term, we must find a solution to the overcrowding in prison, so as to curb the spread of Covid19 among inmates. This includes considering community sentences or parole for those with light offences.

If there is anything that we are learning from Covid-19, it is that we are all equal before it, and we are susceptible to it; and limiting its spread anywhere is the best thing to do for the sake of every one of us.

In the long run, we must look into how we manage our prisons and how we are to transform our judicial system from a punitive one to a more rehabilitative one, particularly for drug offenders.

LIEW CHIN TONG is DAP national political education director. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.