In April, the horrific possibility of animals, from elephants to slow lorises, starving to death behind bars shocked Malaysians.

As is the case the world over, zoos and aquaria in Malaysia are heavily dependent on income from visitors. This income vanished overnight when the country implemented measures to contain Covid-19.

The strict movement control order (MCO) that began on March 18 shut down all public venues indefinitely at the time.

Zoos and aquaria lost as much as 98 percent of their funding, says Kevin Lazarus, chairperson of the Malaysian Association of Zoological Parks and Aquaria (Mazpa).

Within two weeks of the MCO, parks began making desperate pleas for funds.

Income shock

“It’s unprecedented that there was completely no revenue,” said Kevin, a zoo director and veterinarian of 30 years.

“Most zoos found they had funds only for three to four months. One or two were in real difficulty.”

The federal government does not fund zoos. However, their conservation centres do receive government funds and during the MCO, faced no issues feeding animals or paying salaries.

Insecure funding?

For conservationists, the Covid-19 crisis exposed the fragility of the funding model of zoos and therefore, their ability to care for the animals.

“I think zoos have to be held to account. For them to be asking for funds from various sources is a failure on their part.

"They can't survive on their own for a few months; what will happen should the restrictions last much longer?” said a conservationist who declined to be named.

But, as Kevin said, this is unprecedented and the same crisis has affected zoos worldwide.

In Germany’s Neumünster Zoo, keepers drew up a list of animals to slaughter if funds ran out. Likewise, the Bandung Zoo in Indonesia was ready to slaughter their deers to feed the carnivores.

Meanwhile, the British and Irish Association of Zoos and Aquariums had to pressure the government through Parliament to allow parks to reopen “or many will not survive this crisis”.

In Malaysia, parks do not publish their finances and it is unclear how much it costs for them to operate.

As of this year, the federal government had licensed 14 zoos and 20 permanent wildlife exhibition centres in Peninsular Malaysia (see map) and estimated that it cost these parks RM8 million a year to operate.

The licences were issued by the Department of Wildlife and National Parks Peninsular Malaysia (Perhilitan).

However, among these licenced zoos, Zoo Negara alone said it needed about RM1.2 million a month to operate. This is the country’s largest park, home to more than 5,000 wildlife animals.

In any case, appeals for funds by the parks have reached all and sundry, thanks to generous media coverage.

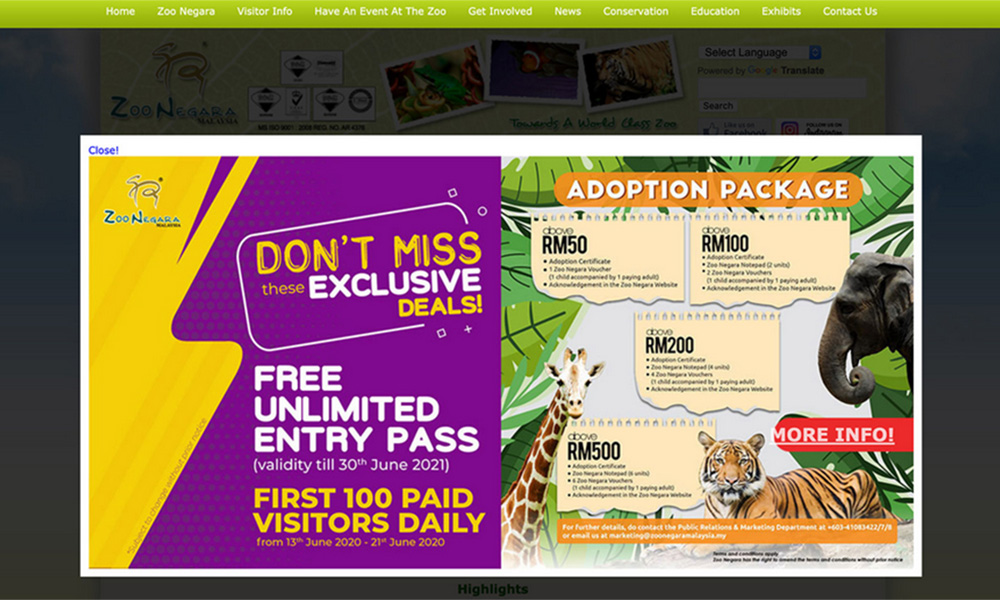

The parks themselves went into social media overdrive with 'adopt-an-animal' posts and inundating netizens with videos of gambolling tapirs, talking birds and "Selamat Hari Raya we miss you" greetings from an orangutan.

Malaysians responded in cash and kind. Millions of ringgit flowed in.

Zoo Negara has been a particularly successful recipient, likely due to the widespread assumption that it is the national zoo - as its name indicates - but the 57-year-old park is actually run by the non-profit Malaysian Zoological Society.

Zoo Negara raised almost RM3 million in donations as of May 7. Animal adoptions got a boost through the new easy-to-use payment channels of ticketing outfit Ticket2u and online shopping giant Lazada.

In addition, fresh produce that would have gone to waste found a happy home at the zoo. This included tonnes of vegetables and unsold produce from food supply chains disrupted by the MCO, and consumable produce seized by the Quarantine and Inspection Services.

Social enterprise Kembara Kitchen, which normally distributes food to the needy, also supplied food to the zoo.

Some relief all round

Other parks have been experiencing similar, though smaller amounts, of relief.

However, Kevin pointed out that government aid has been key.

Mazpa, which represents 22 parks, reached out to the Energy and Natural Resources Ministry for help.

The ministry responded by pledging to help zoos with the costs of food, medicines and sanitation till the end of the year.

Zoo Negara received an RM1.3 million government grant “as an initial step”, as the government put it.

Kevin said other parks are receiving grants based on their respective needs and he noted that staff salaries are being subsidised by the federal government’s Covid-19 Bantuan Prihatin special aid package.

Three months after the MCO implementation, Covid-19 appears to be under control. As Malaysia carefully eases out of the MCO, the hope is that visitors will once again throng the parks.

Kevin said he is confident the sales of tickets and food and beverages, as well as venue rentals, would be able to cover operational costs again, by the year-end.

This article was originally published on Macaranga, a journalism portal covering environment and sustainability in Malaysia. This is the first of a two-part series on zoos and aquaria in its Taking Stock series. Research done by Darshana Dinesh Kumar and contributions from naturalist/photographer Cede Prudente. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.