Malaysia’s second by-election campaign since the backdoor Muhyiddin Yassin Perikatan Nasional (PN) government took power five months ago has officially started, with polling day on Aug 29 before the eve of Merdeka.

A total of 23,094 voters will choose predominantly between Umno’s Felda settler Mohd Zaidi Aziz, 43, and Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s Pejuang candidate, syariah lawyer Amir Khusyairi Mohamad Tanusi, 38 (below, left). There is a third candidate, former school teacher Santharasekaran Subramaniam, 45, who will run as an independent.

Zaidi (below, right) is a local and has played a role in promoting the Felda community, while Khusyairi comes from a prominent religious family and hails from Teluk Intan. He is seen to be connected to the seat through his wife, who works in the local hospital.

On the surface, the contest does not matter – it will not affect the outcome of the Perak state government, as defections and elite dealing have given the PN Perak government the numbers it needs to hold onto the majority (for now).

Yet, a closer look suggests that there is more going on than meets the eye. As with the July Chini by-election that strengthened the hand of Najib Abdul Razak in Umno, the results in Slim will shape Malay politics and ricochet across the evolving and strained relations within both the Pakatan Harapan and PN coalitions.

While most think this is a test for Mahathir and his new party, in reality, this contest is more about Umno and how it is adjusting after the Najib conviction.

I have long believed that Perak is a bellwether of national sentiment, with its rich and tumultuous political history. While Slim is one of the three state seats in the traditionally MCA parliamentary seat of Tanjong Malim that has long favoured Barisan Nasional (BN), this changed in GE14 when PKR’s vice-president Chang Lih Kang captured the seat.

This time around, the outcome in the Malay-majority Slim will matter – although as is often the case in Malay politics, developments behind the scenes, as opposed to those easier seen, may be more important.

A look at the seat - past voting patterns and the role of behind-the-scenes strained relationships - shows that the seat is competitive. New but chip-off-the-old-block Mahathir’s Pejuang nevertheless faces an uphill battle.

Old M’sian charm facing change

Slim is a state seat that echoes of old Malaysia, not the tainted political old, but the charm of life in semi-urban and rural areas. Small kampungs pepper this constituency, with large numbers of Felda settlers. The food is good, priced reasonably, and its hospitality welcoming.

Perhaps the most resonant feature of old Malaysia – which can be found across Perak – is the cordial race relations among the different communities, as friends and families have known each other for generations and continue to share lives together, as opposed to merely living parallel to each other.

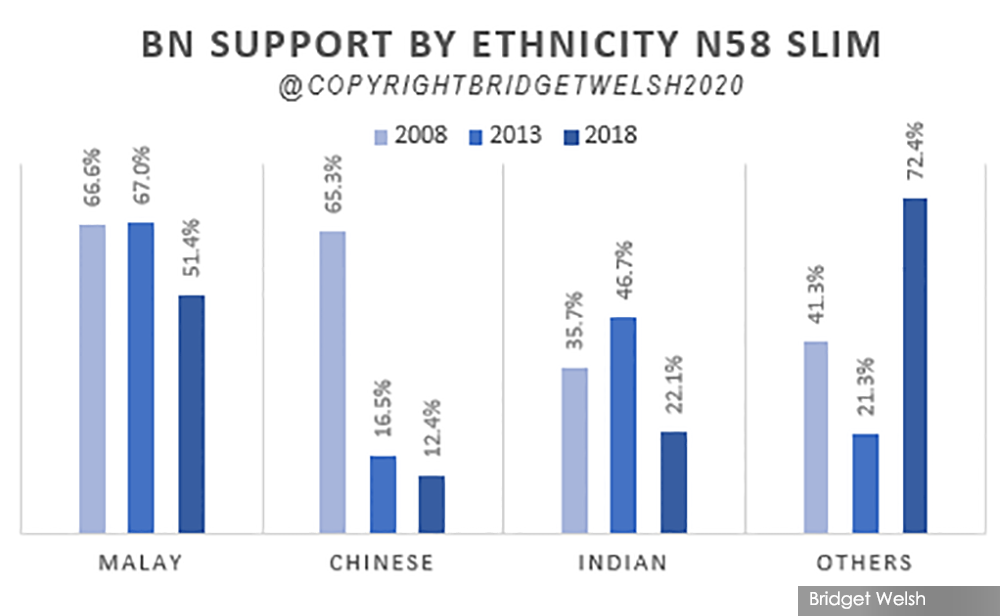

The seat is ethnically diverse, typical of Perak’s composition. The Slim constituency is comprised of 75 percent Malays, 10 percent Chinese, 13 percent Indians, and two percent Orang Asli, with the Malay and Orang Asli communities living in the more rural areas. Communities are tight, with family networks strong, making these local social ties especially important in winning political support.

At the same time, the constituency wrestles with development and conditions are challenging. There are strains on the environment and in places, bottlenecks from inadequate infrastructure provision clog up traffic.

The predominant activity is agriculture. One of the legacies of the popular four-term assemblyman Khusairi Abdul Talib, whose passing triggered the by-election, is growing diversification of the area’s agriculture as rubber and palm oil holdings become more interspersed with tapioca and fruits, notably a lovely sweet pineapple.

These second-generation Felda settlers are using more technology and digitising their production and access to markets. There are bustling signs of entrepreneurship as well, as unlike some other semi-rural/rural areas, there is a buzz of activity with farmers and small businesses trying to survive in these difficult times.

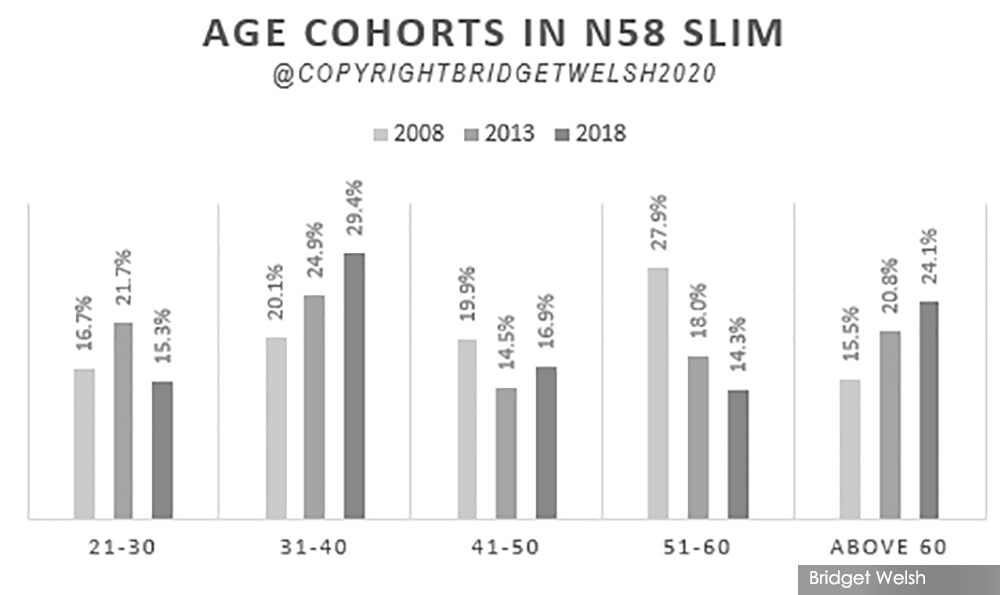

Yet this constituency faces a common Perak problem: outmigration. Voter numbers do not increase significantly in many Perak seats like Slim. For generations, younger Perakians have migrated for work. You can often find a Perakian (usually from Ipoh) running a Malaysian restaurant overseas. These days, most leave Slim for work within Malaysia, or as far as Singapore.

Of the Slim voters, a minimum estimate of 20% or 4,600 voters work outside the constituency – enough to shape an outcome in a close race. There are efforts underway to bring them home, as happened in Chini, with the issue of turnout crucial in shaping the by-election’s final outcome. Machinery will be a factor in the election, a disadvantage to Pejuang that will have to rely on its partners for help.

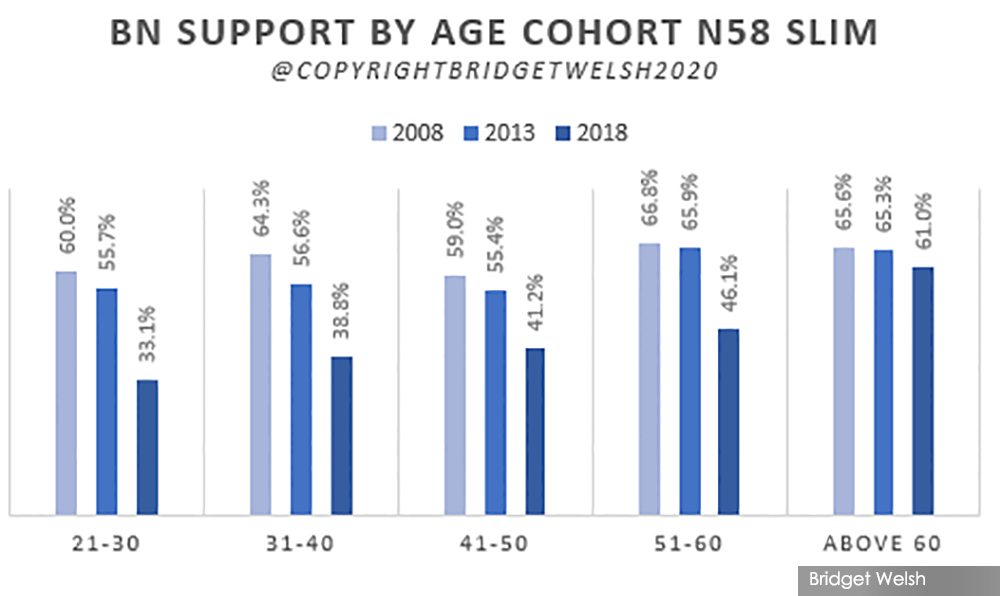

Slim also reflects another demographic reality of predominant Felda areas, large numbers of older voters, with nearly a quarter over the age of 60. These older voters have traditionally been Umno supporters, as Slim has been an Umno stronghold for decades. BN won 61% of older voters in GE14, and this has been remained consistent over elections.

Fissures in Umno support

This emphasis on traditional loyalties is the surface story – all things being equal, this seat would be a sure decisive win for Umno. Former assemblyperson Khusairi was well-liked, and many would support his Umno deputy division chief Mohd Zaidi Aziz as his chosen successor on sentiment alone.

Traditionally, Umno does well in by-elections if the former representative was popular. This is the scenario Umno is hoping for; a big win, where the issue is the size of the majority a.k.a. Chini.

Yet the seat negotiations among Muafakat Nasional (MN) partners and within Umno were fractious. It is not clear whether Umno’s chosen candidate Zaidi can capitalise on the support of his former boss.

The reason is that the Malay vote has become more divided, and the seat has become more competitive.

But Perak is not Pahang. Umno only won the Slim seat by a majority of 2,183 votes in GE14. It captured an estimated 51.4% of the Malay vote, barely a majority. For Pejuang to win, it will need continued division in the Malay vote.

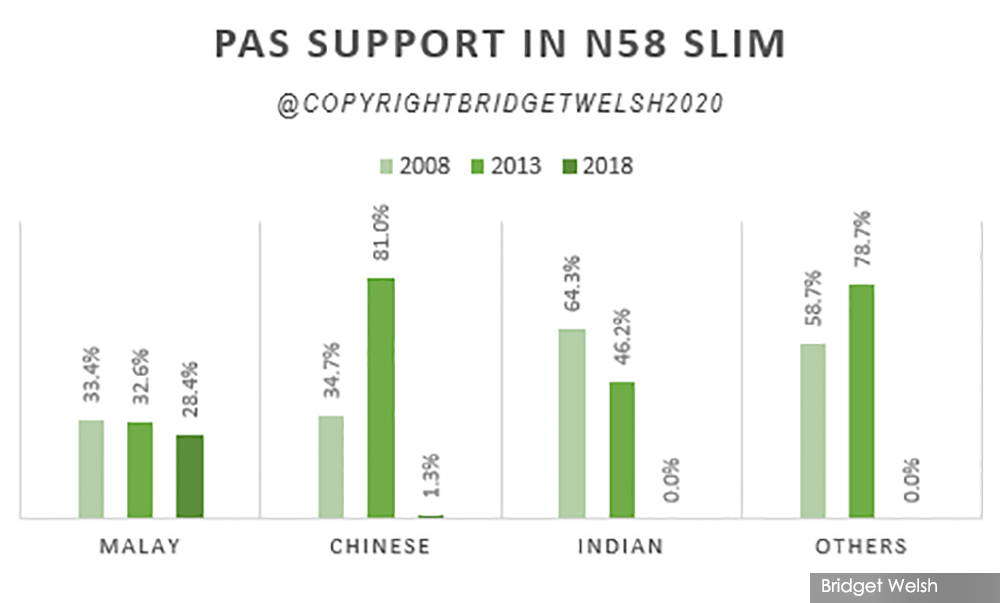

Slim has long had Malay splits in voting. In GE14, PAS was a political force in Slim, securing 22% of the overall vote and 28% of the Malay vote in GE14. PAS supporters in Slim are largely Felda settlers originating from Kedah and have strong ties to the Islamist party. PAS’ support however has declined precipitously as the party lost support among non-Malays and even lost Malay support (4%) to Bersatu in GE14. PAS struggles – and the party will continue to struggle – in competitive ethnically mixed seats.

In this by-election, PAS was summarily dismissed during recent MN seat negotiations. Many PAS loyalists in Slim did not like being so cavalierly tossed aside. From Kedah and Terengganu to Perak, PAS grassroots are becoming more disgruntled with their MN and PN alliance partners, as seat negotiations move to the local level. They are questioning the decisions of their national leaders as on-the-ground differences in political outlooks set in.

With Pejuang’s choice of Khusyairi and his strong religious background, this by-election will test whether loyalty to party or the religious standing of a candidate is more important. If PAS supporters stick with Umno, the party will have a fat win in Slim. If not, Umno’s chances slim down.

Keeping, or losing, core supporters

Previous voting patterns show Umno’s political advantage far exceeds that of Mahathir’s Pejuang. So far, I have pointed to two groups that can shape the outcome – the return of outstation voters (disproportionately younger voters), and PAS supporters.

There are four other important groups – minorities, younger and reformasi generation voters, and women – that will shape the outcome. In looking at these groups, it is clear that what is at play is whether Mahathir, now as Pejuang, or Umno can hold onto their political base.

Mahathir needs non-Malays support. In GE14, the group that saved Umno were Orang Asli, (with 72% support), while Bersatu’s support came from Indians (78%) and Chinese (86%). Pejuang needs continued high Indian and Chinese support (comprising nearly a quarter 23% of the electorate) to win.

National support among these communities eroded in Harapan by-elections, as disappointment with Mahathir’s leadership set in. Slim will be a test to see whether PN’s exclusion of minorities in the government and emotive responses to the charging of a prominent now opposition leader Lim Guan Eng will shift support back to Harapan-aligned Pejuang.

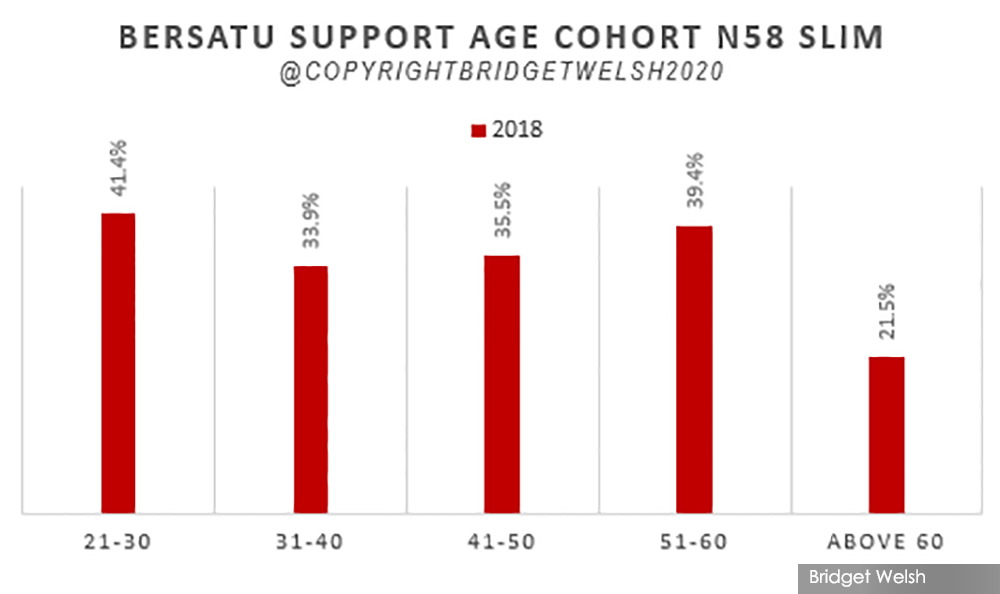

One-third of Bersatu’s GE14 Slim votes came from non-Malays. It only captured 20% of Malay vote in Slim. A good share of this came from younger voters, younger Malays. This is the same group that predominantly live outside the constituency. Pejuang does not match Umno’s machinery and resources to bring them back. Even if younger voters came back, it is not clear that they would vote for Mahathir’s party, as it is the young who first abandoned Bersatu electorally in Harapan by-elections.

A second noteworthy age cohort is reformasi voters, those shaped by the events of the 1998-1999 period, now in their 50s. This age group has traditionally leaned opposition, namely non-Mahathir opposition. Whether Mahathir’s Pejuang can retain their support in his new vehicle is not clear, but it will be very difficult for the party to reach GE14 levels.

Mahathir just does not have the pull. Unlike in other seats where Mahathir brought older voters above 60 to his side, this was not the case in Slim. Umno maintained the loyalty of this core.

They did so for another important group as well, women - especially Malay women. Slim is an example where Wanita Umno was effective. This time, Umno opted to exclude women in their Slim candidate list and was seen as dismissive of inputs from local women leaders. Pejuang was no better, there was not a woman in sight. So far, all of the parties have marginalised women leaders. Whoever ignores women in Slim will lose - ultimately no man is going to get into office without female support.

Strained partnerships

While voting trends and Pejuang’s newbie-oldbie status do not lean in their favour in Slim, it is the fluid and contentious national developments that are flowing through the constituency that make the contest more competitive. Coalitions alliances are strained.

Umno is a weakened and seriously divided party and its relationship to its grassroots base is being tested in Slim. Its de facto leader Najib is a convicted man, and there is real opposition to his leadership within the party. His shadow still casts a dark cloud. Umno president Ahmad Zahid Hamidi also faces resistance from the grassroots.

The internal problems Umno faced in deciding their Slim candidate reflects a growing lack of confidence in the party’s leadership among party members. Questions are being asked: Who gets to decide? The division? The members? The leaders? And should the candidate decision be accepted?

These issues continue to percolate, as there is open disgruntlement among Umno grassroots on how and who was chosen as candidate. How these differences and delegitimisation of Umno’s party leadership will affect the party machinery and the spillover to other voters will be crucial.

Umno also needs to work with MCA, who are still sore after losing the Tanjong Malim parliamentary seat in GE14. The fact is that without Najib, the party would have held onto its core Perak seat. They have very little at stake if Umno wins Slim. Umno is, after all, demanding Tanjong Malim for themselves. Given Malay divisions, Umno will need its BN allies and current PN ties for electoral support, including from non-Mahathir aligned Bersatu members. The reality is that there are strains on loyalties, which are being further frayed by Umno splits.

Harapan, on its part, faces the same serious problem of internal divisions. Slim is the first test for Mahathir’s electoral performance since the fall of Harapan government and there are interests inside the coalition that want to see him win (and lose). Mahathir needs support from Amanah that has a base in the area, holding the neighbouring state seat of Behrang that it won by a very tight margin of 409 votes in GE14. Pejuang will also need the support of DAP and PKR as well, and, from Kuala Lumpur; the latter has not been openly forthcoming.

For both coalitions, there are interests working to undermine each other, reinforcing the view that the outcome will be shaped by what cannot be seen, rather than what is being said or openly done.

Does Mahathir’s Pejuang have a chance to win? Yes, it has a slim chance. The seat is competitive and politics nationally and locally remain volatile, reflecting changing currents on the national stage. But ultimately, given that this is Mahathir’s first election as Pejuang, the result will reflect more on the health of Umno politics and its alliance with PAS, MCA and Bersatu, all of which have not fared well since Najib’s guilty verdict.

BRIDGET WELSH is a Senior Research Associate at the Hu Fu Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies, a Senior Associate Fellow of The Habibie Centre, and a University Fellow of Charles Darwin University. She currently is an Honorary Research Associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia's Asia Research Institute (Unari) based in Kuala Lumpur. - Mkini

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of us.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.